19.21: Single Covalent Bonds

- Page ID

- 102016

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)What holds molecules together?

In one form or another, the idea of atoms connecting to form larger substances has been with us for a long time. The Greek philosopher Democritus (460-370 BCE) believed that atoms had hooks that allowed them to connect with one another. Today, we believe that atoms are held together by bonds formed when two atoms share a set of electrons—a much more complicated picture than the simple hooks that Democritus believed in.

Single Covalent Bonds

A covalent bond forms when two orbitals with one electron each overlap one another. For the hydrogen molecule, this can be shown as:

Upon formation of the \(\ce{H_2}\) molecule, the shared electrons must have opposite spin, so they are shown with opposite spin in the atomic \(1s\) orbital.

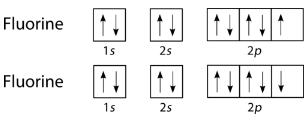

The halogens also form single covalent bonds in their diatomic molecules. An atom of any halogen, such as fluorine, has seven valence electrons. Its unpaired electron is located in the \(2p\) orbital.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) (CC BY-NC 3.0; Joy Sheng via CK-12 Foundation)

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) (CC BY-NC 3.0; Joy Sheng via CK-12 Foundation)

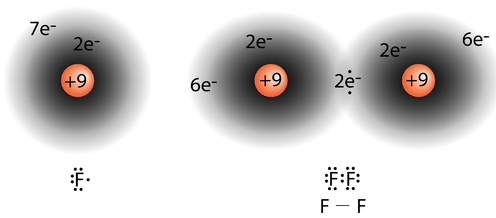

The single electrons in the third \(2p\) orbital combine to form the covalent bond:

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): On the left is a fluorine atom with seven valence electrons. On the right is the \(\ce{F_2}\) molecule. (CC BY-NC 3.0; Jodi So via CK-12 Foundation)

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): On the left is a fluorine atom with seven valence electrons. On the right is the \(\ce{F_2}\) molecule. (CC BY-NC 3.0; Jodi So via CK-12 Foundation)

The diatomic fluorine molecule \(\left( \ce{F_2} \right)\) contains a single shared pair of electrons. Each \(\ce{F}\) atom also has three pair of electrons that are not shared with the other atom. A lone pair is a pair of electrons in a Lewis electron-dot structure that is not shared between atoms. The oxygen atom in the water molecule shown below has two lone pair sets of electrons. Each \(\ce{F}\) atom has three lone pairs. Combined with the two electrons in the covalent bond, each \(\ce{F}\) atom follows the octet rule.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Draw the Lewis electron dot structure for water.

Solution

Step 1: List the known quantities and plan the problem.

Known

- Molecular formula of water \(= \ce{H_2O}\)

- \(1 \: \ce{O}\) atom \(= 6\) valence electrons

- \(2 \: \ce{H}\) atoms \(=2 \times 1 = 2\) valence electrons

- Total number of valence electrons \(=8\)

Use the periodic table to determine the number of valence electrons for each atom and the total number of valence electrons. Arrange the atoms and distribute the electrons so that each atom follows the octet rule. The oxygen atom will have 8 electrons, while the hydrogen atoms will each have 2.

Step 2: Solve.

Electron dot diagrams for each atom are:

Each hydrogen atom with its single electron will form a covalent bond with the oxygen atom where it has a single electron. The resulting Lewis electron dot structure is:

Step 3: Think about your result.

The oxygen atom follows the octet rule with two pairs of bonding electrons and two lone pairs. Each hydrogen atom follows the octet rule with one bonding pair of electrons.

Summary

- Covalent bonds form when electrons in two atoms form overlapping orbitals.

- Lone pair electrons in an atom are not shared with any other atom.

Review

- How does a covalent bond form?

- What relationship do the spins of shared electrons have with each other?

- Do lone pair electrons form covalent bonds?