14.9: Worked Examples

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Example 14.2 Escape Velocity of Toro

The asteroid Toro, discovered in 1964, has a radius of about R=5.0km and a mass of about mt=2.0×1015kg. Let’s assume that Toro is a perfectly uniform sphere. What is the escape velocity for an object of mass m on the surface of Toro? Could a person reach this speed (on earth) by running?

Solution: The only potential energy in this problem is the gravitational potential energy. We choose the zero point for the potential energy to be when the object and Toro are an infinite distance apart, UG(∞)≡0. With this choice, the potential energy when the object and Toro are a finite distance r apart is given by

UG(r)=−Gmtmr

with UG(∞)≡0 The expression escape velocity refers to the minimum speed necessary for an object to escape the gravitational interaction of the asteroid and move off to an infinite distance away. If the object has a speed less than the escape velocity, it will be unable to escape the gravitational force and must return to Toro. If the object has a speed greater than the escape velocity, it will have a non-zero kinetic energy at infinity. The condition for the escape velocity is that the object will have exactly zero kinetic energy at infinity.

We choose our initial state, at time ti, when the object is at the surface of the asteroid with speed equal to the escape velocity. We choose our final state, at time tf, to occur when the separation distance between the asteroid and the object is infinite.

The initial kinetic energy is Ki=(1/2)mv2esc. The initial potential energy is Ui=−Gmtm/R and so the initial mechanical energy is

Ei=Ki+Ui=12mv2esc−GmtmR

The final kinetic energy is Kf=0 because this is the c

ondition that defines the escape velocity. The final potential energy is zero, Uf=0 because we chose the zero point for potential energy at infinity. The final mechanical energy is then

Ef=Kf+Uf=0

There is no non-conservative work, so the change in mechanical energy is zero

0=Wnc=ΔEm=Ef−Ei

Therefore

0=−(12mv2esc−GmtmR)

This can be solved for the escape velocity,

vesc=√2GmtR=√2(6.67×10−11N⋅m2⋅kg−2)(2.0×1015kg)(5.0×103m)=7.3m⋅s−1

Considering that Olympic sprinters typically reach velocities of 12m⋅s−1, this is an easy speed to attain by running on earth. It may be harder on Toro to generate the acceleration necessary to reach this speed by pushing off the ground, since any slight upward force will raise the runner’s center of mass and it will take substantially more time than on earth to come back down for another push off the ground.

Example 14.3 Spring-Block-Loop-the-Loop

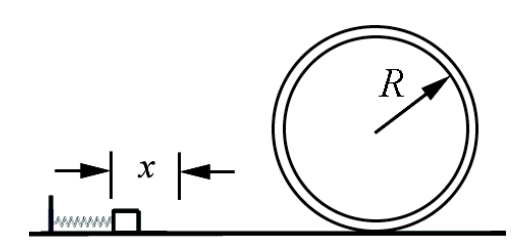

A small block of mass m is pushed against a spring with spring constant k and held in place with a catch. The spring is compressed an unknown distance x (Figure 14.12). When the catch is removed, the block leaves the spring and slides along a frictionless circular loop of radius r . When the block reaches the top of the loop, the force of the loop on the block (the normal force) is equal to twice the gravitational force on the mass. (a) Using conservation of energy, find the kinetic energy of the block at the top of the loop. (b) Using Newton’s Second Law, derive the equation of motion for the block when it is at the top of the loop. Specifically, find the speed vtop in terms of the gravitation constant g and the loop radius r . (c) What distance was the spring compressed?

Solution: a) Choose for the initial state the instant before the catch is released. The initial kinetic energy is Ki=0. The initial potential energy is non-zero, Ui=(1/2)kx2. The initial mechanical energy is then

Ei=Ki+Ui=12kx2

Choose for the final state the instant the block is at the top of the loop. The final kinetic energy is Kf=(1/2)mv2top ; the block is in motion with speed vtop . The final potential energy is non-zero, Uf=(mg)(2R). The final mechanical energy is then

Ef=Kf+Uf=2mgR+12mv2top

Because we are assuming the track is frictionless and neglecting air resistance, there is no non- conservative work. The change in mechanical energy is therefore zero,

0=Wnc=ΔEm=Ef−Ei

Mechanical energy is conserved, Ef=Ei, therefore

2mgR+12mv2top=12kx2

From Equation (14.8.10), the kinetic energy at the top of the loop is

12mv2top=12kx2−2mgR

b) At the top of the loop, the forces on the block are the gravitational force of magnitude mg and the normal force of magnitude N , both directed down. Newton’s Second Law in the radial direction, which is the downward direction, is

−mg−N=−mv2topR

In this problem, we are given that when the block reaches the top of the loop, the force of the loop on the block (the normal force, downward in this case) is equal to twice the weight of the block, N = 2mg . The Second Law, Equation (14.8.12), then becomes

3mg=mv2topR

We can rewrite Equation (14.8.13) in terms of the kinetic energy as

32mgR=12mv2top

The speed at the top is therefore

vtop=√3mgR

c) Combing Equations (14.8.11) and (14.8.14) yields

72mgR=12kx2

Thus the initial displacement of the spring from equilibrium is

x=√7mgRk

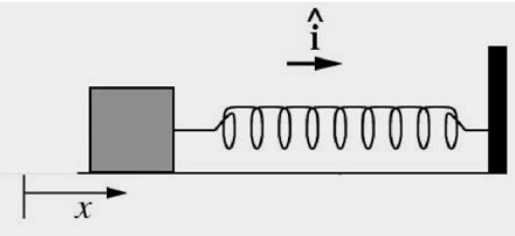

Example 14.4 Mass-Spring on a Rough Surface

A block of mass m slides along a horizontal table with speed v0. At x = 0 it hits a spring with spring constant k and begins to experience a friction force. The coefficient of friction is variable and is given by μ=bx, where b is a positive constant. Find the loss in mechanical energy when the block first momentarily comes to rest.

Solution: From the model given for the frictional force, we could find the nonconservative work done, which is the same as the loss of mechanical energy, if we knew the position xf where the block first comes to rest. The most direct (and easiest) way to find xf is to use the work-energy theorem. The initial mechanical energy is Ei=mv2i/2 and the final mechanical energy is Ef=kx2f/2 (note that there is no potential energy term in Ei and no kinetic energy term Ef The difference between these two mechanical energies is the non-conservative work done by the frictional force,

Wnc=∫x=xfx=0Fncdx=∫x=xfx=0−Ffrictiondx=∫x=xfx=0−μNdx=−∫xf0bxmgdx=−12bmgx2f

We then have that

Wnc=ΔEmWnc=Ef−Ei−12bmgx2f=12kx2f−12mv2i

Solving the last of these equations for x2f yields

x2f=mv20k+bmg

Substitute Equation (14.8.20) into Equation (14.8.18) gives the result that

Wnc=−bmg2mv20k+bmg=−mv202(1+kbmg)−1

It is worth checking that the above result is dimensionally correct. From the model, the parameter b must have dimensions of inverse length (the coefficient of friction μ must be dimensionless), and so the product bmg has dimensions of force per length, as does the spring constant k; the result is dimensionally consistent.

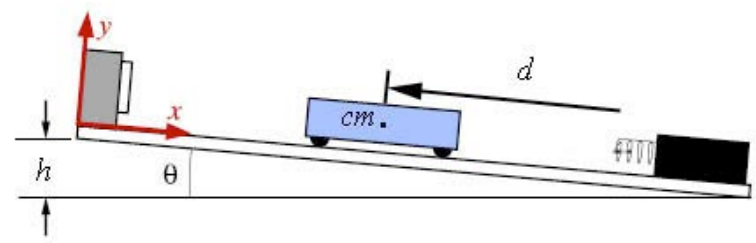

Example 14.5 Cart-Spring on an Inclined Plane

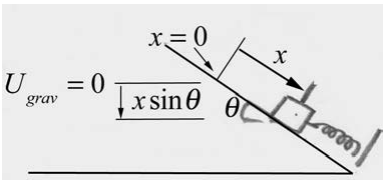

An object of mass m slides down a plane that is inclined at an angle θ from the horizontal (Figure 14.14). The object starts out at rest. The center of mass of the cart is a distance d from an unstretched spring that lies at the bottom of the plane. Assume the spring is massless, and has a spring constant k . Assume the inclined plane to be frictionless. (a) How far will the spring compress when the mass first comes to rest? (b) Now assume that the inclined plane has a coefficient of kinetic friction μk How far will the spring compress when the mass first comes to rest? The friction is primarily between the wheels and the bearings, not between the cart and the plane, but the friction force may be modeled by a coefficient of friction μk. . (c) In case (b), how much energy has been lost to friction?

Solution: Let x denote the displacement of the spring from the equilibrium position. Choose the zero point for the gravitational potential energy Ug(0)=0 not at the very bottom of the inclined plane, but at the location of the end of the unstretched spring. Choose the zero point for the spring potential energy where the spring is at its equilibrium position, Us(0)=0

a) Choose for the initial state the instant the object is released (Figure 14.15). The initial kinetic energy is Ki=0. The initial potential energy is non-zero, Ui=mgdsinθ. The initial mechanical energy is then

Ei=Ki+Ui=mgdsinθ

Choose for the final state the instant when the object first comes to rest and the spring is compressed a distance x at the bottom of the inclined plane (Figure 14.16). The final kinetic energy is Kf=0 since the mass is not in motion. The final potential energy is non-zero, Uf=kx2/2−xmgsinθ Notice that the gravitational potential energy is negative because the object has dropped below the height of the zero point of gravitational potential energy.

The final mechanical energy is then

Ef=Kf+Uf=12kx2−xmgsinθ

Because we are assuming the track is frictionless and neglecting air resistance, there is no non- conservative work. The change in mechanical energy is therefore zero,

0=Wnc=ΔEm=Ef−Ei

Therefore

dmgsinθ=12kx2−xmgsinθ

This is a quadratic equation in x ,

x2−2mgsinθkx−2dmgsinθk=0

In the quadratic formula, we want the positive choice of square root for the solution to ensure a positive displacement of the spring from equilibrium,

x=mgsinθk+(m2g2sin2θk2+2dmgsinθk)1/2=mgk(sinθ+√1+2(kd/mg)sinθ)

(What would the solution with the negative root represent?)

b) The effect of kinetic friction is that there is now a non-zero non-conservative work done on the object, which has moved a distance, d+x, given by

Wnc=−fk(d+x)=−μkN(d+x)=−μkmgcosθ(d+x)

Note the normal force is found by using Newton’s Second Law in the perpendicular direction to the inclined plane,

N−mgcosθ=0

The change in mechanical energy is therefore

Wnc=ΔEm=Ef−Ei

which becomes

−μkmgcosθ(d+x)=(12kx2−xmgsinθ)−dmgsinθ

Equation (14.8.31) simplifies to

0=(12kx2−xmg(sinθ−μkcosθ))−dmg(sinθ−μkcosθ)

This is the same as Equation (14.8.25) above, but with sinθ→sinθ−μkcosθ. The maximum displacement of the spring is when there is friction is then

x=mgk((sinθ−μkcosθ)+√1+2(kd/mg)(sinθ−μkcosθ))

c) The energy lost to friction is given by Wnc=−μkmgcosθ(d+x) where x is given in part b).

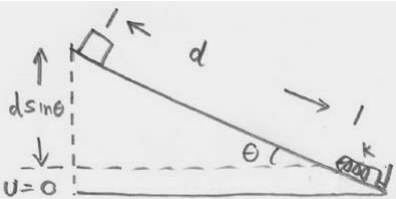

Example 14.6 Object Sliding on a Sphere

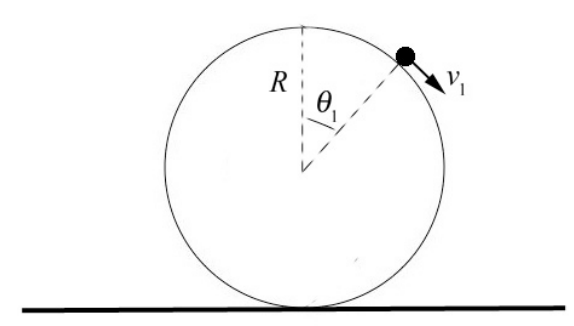

A small point like object of mass m rests on top of a sphere of radius R . The object is released from the top of the sphere with a negligible speed and it slowly starts to slide (Figure 14.17). Let g denote the gravitation constant. (a) Determine the angle θ1 with respect to the vertical at which the object will lose contact with the surface of the sphere. (b) What is the speed v1 of the object at the instant it loses contact with the surface of the sphere.

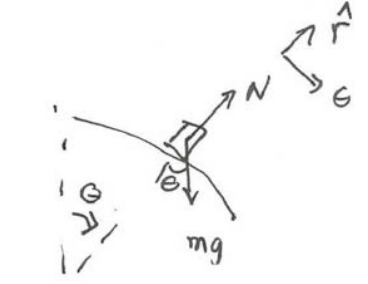

Solution: We begin by identifying the forces acting on the object. There are two forces acting on the object, the gravitation and radial normal force that the sphere exerts on the particle that we denote by N . We draw a free-body force diagram for the object while it is sliding on the sphere. We choose polar coordinates as shown in Figure 14.18.

The key constraint is that when the particle just leaves the surface the normal force is zero,

N(θ1)=0

where θ1 denotes the angle with respect to the vertical at which the object will just lose contact with the surface of the sphere. Because the normal force is perpendicular to the displacement of the object, it does no work on the object and hence conservation of energy does not take into account the constraint on the motion imposed by the normal force. In order to analyze the effect of the normal force we must use the radial component of Newton’s Second Law,

N−mgcosθ=−mv2R

Then when the object just loses contact with the surface, Equations (14.8.34) and (14.8.35) require that

mgcosθ1=mv21R

where v1 denotes the speed of the object at the instant it loses contact with the surface of the sphere. Note that the constrain condition Equation (14.8.36) can be rewritten as

mgRcosθ1=mv21

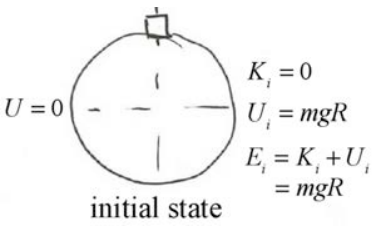

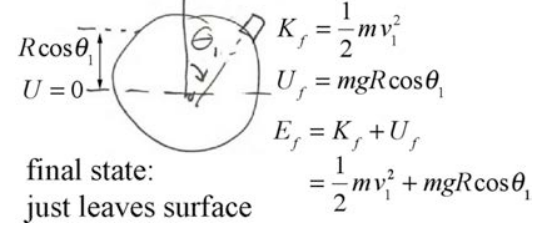

We can now apply conservation of energy. Choose the zero reference point U = 0 for potential energy to be the midpoint of the sphere.

Identify the initial state as the instant the object is released (Figure 14.19). We can neglect the very small initial kinetic energy needed to move the object away from the top of the sphere and so Ki=0. The initial potential energy is non-zero, Ui=mgR. The initial mechanical energy is then

Ei=Ki+Ui=mgR

Choose for the final state the instant the object leaves the sphere (Figure 14.20). The final kinetic energy is Kf=mv21/2; the object is in motion with speed v1. The final potential energy is non-zero, Uf=mgRcosθ1. The final mechanical energy is then

Ef=Kf+Uf=12mv21+mgRcosθ1

Because we are assuming the contact surface is frictionless and neglecting air resistance, there is no non-conservative work. The change in mechanical energy is therefore zero,

0=Wnc=ΔEm=Ef−Ei

Therefore

12mv21+mgRcosθ1=mgR

We now solve the constraint condition Equation (14.8.37) into Equation (14.8.41) yielding

12mgRcosθ1+mgRcosθ1=mgR

We can now solve for the angle at which the object just leaves the surface

θ1=cos−1(2/3)

We now substitute this result into Equation (14.8.37) and solve for the speed

v1=√2gR/3