13.4: Kinetic Theory- Atomic and Molecular Explanation of Pressure and Temperature

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Express the ideal gas law in terms of molecular mass and velocity.

- Define thermal energy.

- Calculate the kinetic energy of a gas molecule, given its temperature.

- Describe the relationship between the temperature of a gas and the kinetic energy of atoms and molecules.

- Describe the distribution of speeds of molecules in a gas.

We have developed macroscopic definitions of pressure and temperature. Pressure is the force divided by the area on which the force is exerted, and temperature is measured with a thermometer. We gain a better understanding of pressure and temperature from the kinetic theory of gases, which assumes that atoms and molecules are in continuous random motion.

Figure shows an elastic collision of a gas molecule with the wall of a container, so that it exerts a force on the wall (by Newton’s third law). Because a huge number of molecules will collide with the wall in a short time, we observe an average force per unit area. These collisions are the source of pressure in a gas. As the number of molecules increases, the number of collisions and thus the pressure increase. Similarly, the gas pressure is higher if the average velocity of molecules is higher. The actual relationship is derived in the Things Great and Small feature below. The following relationship is found:

PV=13Nm¯v2,

What can we learn from this atomic and molecular version of the ideal gas law? We can derive a relationship between temperature and the average translational kinetic energy of molecules in a gas. Recall the previous expression of the ideal gas law:

PV=NkT.

Equating the right-hand side of this equation with the right-hand side of PV=13Nmv2 gives

13Nm¯v2=NkT.

Making Connections: Things Great and Small—Atomic and Molecular Origin

of Pressure in a Gas

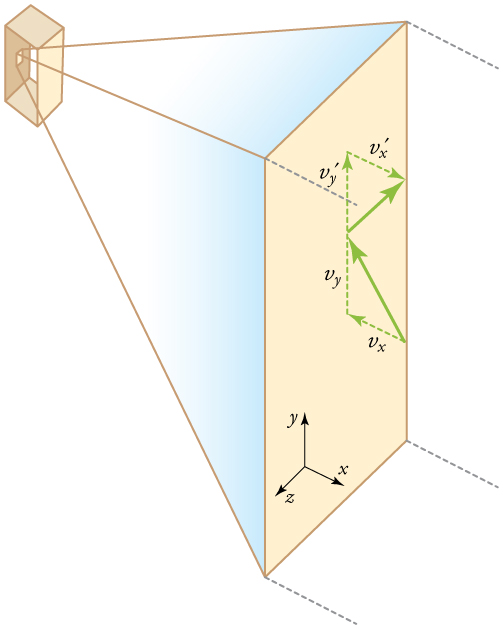

Figure shows a box filled with a gas. We know from our previous discussions that putting more gas into the box produces greater pressure, and that increasing the temperature of the gas also produces a greater pressure. But why should increasing the temperature of the gas increase the pressure in the box? A look at the atomic and molecular scale gives us some answers, and an alternative expression for the ideal gas law.

The figure shows an expanded view of an elastic collision of a gas molecule with the wall of a container. Calculating the average force exerted by such molecules will lead us to the ideal gas law, and to the connection between temperature and molecular kinetic energy. We assume that a molecule is small compared with the separation of molecules in the gas, and that its interaction with other molecules can be ignored. We also assume the wall is rigid and that the molecule’s direction changes, but that its speed remains constant (and hence its kinetic energy and the magnitude of its momentum remain constant as well). This assumption is not always valid, but the same result is obtained with a more detailed description of the molecule’s exchange of energy and momentum with the wall.

If the molecule’s velocity changes in the x-direction, its momentum changes from −mvx to +mvx. Thus, its change in momentum is Δmv=+mvx−(−mvx)=2mvx. The force exerted on the molecule is given by

F=ΔpΔt=2mvxΔt.

There is no force between the wall and the molecule until the molecule hits the wall. During the short time of the collision, the force between the molecule and wall is relatively large. We are looking for an average force; we take Δt to be the average time between collisions of the molecule with this wall. It is the time it would take the molecule to go across the box and back (a distance 2l) at a speed of vx. Thus Δt=2l/vx, and the expression for the force becomes

F=2mvx2l/vx=mv2xl.

This force is due to one molecule. We multiply by the number of molecules N and use their average squared velocity to find the force

F=Nm¯v2xl,

¯v2=¯v2x+¯v2y+¯v2z.

Because the velocities are random, their average components in all directions are the same:

¯v2x=¯v2y=¯v2z

Thus, ¯v2=3¯v2x,

¯v2x=13¯v2.

Substituting 13¯v2 into the expression for F gives

F=Nm¯v233l.

The pressure is F/A, so that we obtain

P=FA=Nm¯v23Al=13Nm¯v2V,

where we used V=Al for the volume. This gives the important result.

PV=13Nm¯v2.

This equation is another expression of the ideal gas law.

We can get the average kinetic energy of a molecule, 12mv2, from the right-hand side of the equation by canceling N and multiplying by 3/2. This calculation produces the result that the average kinetic energy of a molecule is directly related to absolute temperature.

¯KE=12m¯v2=32kT

The average translational kinetic energy of a molecule, ¯KE, is called thermal energy. The equation ¯KE=12m¯v2=32kT

is a molecular interpretation of temperature, and it has been found to be valid for gases and reasonably accurate in liquids and solids. It is another definition of temperature based on an expression of the molecular energy.

It is sometimes useful to rearrange ¯KE=12m¯v2=32kT and solve for the average speed of molecules in a gas in terms of temperature,

√¯v2=vrms=√3kTm,

Example 13.4.1: Calculating Kinetic Energy and Speed of a Gas Molecule

(a) What is the average kinetic energy of a gas molecule at 20oC (room temperature)? (b) Find the rms speed of a nitrogen molecule (N2)

at this temperature.

Strategy for (a)

The known in the equation for the average kinetic energy is the temperature.

¯KE=12m¯v2=32kT

Before substituting values into this equation, we must convert the given temperature to kelvins. This conversion gives T=(20.0+273)k=293K.

Solution for (a)

The temperature alone is sufficient to find the average translational kinetic energy. Substituting the temperature into the translational kinetic energy equation gives

¯KE=32kT=32(1.38×10−23J/K)(293K)=6.07×10−21J.

Strategy for (b)

Finding the rms speed of a nitrogen molecule involves a straightforward calculation using the equation

√¯v2=vrms=√3kTm,

m=2(14.0067)×10−3kg/mol6.02×1023mol−1=4.65×10−26kg.

Solution for (b)

Substituting this mass and the value for k into the equation for vrms yields

vrms=√3(1.38×10−23J/K)(293)4.65×10−26kg=511m/s.

Discussion

Note that the average kinetic energy of the molecule is independent of the type of molecule. The average translational kinetic energy depends only on absolute temperature. The kinetic energy is very small compared to macroscopic energies, so that we do not feel when an air molecule is hitting our skin. The rms velocity of the nitrogen molecule is surprisingly large. These large molecular velocities do not yield macroscopic movement of air, since the molecules move in all directions with equal likelihood. The mean free path (the distance a molecule can move on average between collisions) of molecules in air is very small, and so the molecules move rapidly but do not get very far in a second. The high value for rms speed is reflected in the speed of sound, however, which is about 340 m/s at room temperature. The faster the rms speed of air molecules, the faster that sound vibrations can be transferred through the air. The speed of sound increases with temperature and is greater in gases with small molecular masses, such as helium. (See Figure.)

Making Connections: Historical Note—Kinetic

Theory of Gases

- The kinetic theory of gases was developed by Daniel Bernoulli (1700–1782), who is best known in physics for his work on fluid flow (hydrodynamics). Bernoulli’s work predates the atomistic view of matter established by Dalton.

Distribution of Molecular Speeds

The motion of molecules in a gas is random in magnitude and direction for individual molecules, but a gas of many molecules has a predictable distribution of molecular speeds. This distribution is called the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, after its originators, who calculated it based on kinetic theory, and has since been confirmed experimentally. (See Figure.) The distribution has a long tail, because a few molecules may go several times the rms speed. The most probable speed is less than the rms speed vrms. Figure shows that the curve is shifted to higher speeds at higher temperatures, with a broader range of speeds.

The distribution of thermal speeds depends strongly on temperature. As temperature increases, the speeds are shifted to higher values and the distribution is broadened.

What is the implication of the change in distribution with temperature shown in Figure for humans? All other things being equal, if a person has a fever, he or she is likely to lose more water molecules, particularly from linings along moist cavities such as the lungs and mouth, creating a dry sensation in the mouth.

Example 13.4.2: Calculating Temperature: Escape Velocity of Helium Atoms

In order to escape Earth’s gravity, an object near the top of the atmosphere (at an altitude of 100 km) must travel away from Earth at 11.1 km/s. This speed is called the escape velocity. At what temperature would helium atoms have an rms speed equal to the escape velocity?

Strategy

Identify the knowns and unknowns and determine which equations to use to solve the problem.

Solution

1. Identify the knowns: v is the escape velocity, 11.1 km/s.

2. Identify the unknowns: We need to solve for temperature, T. We also need to solve for the mass m

of the helium atom.

3. Determine which equations are needed.

- To solve for mass m of the helium atom, we can use information from the periodic table: m=molarmassnumberofatomspermole.

- To solve for temperature T, we can rearrange either ¯KE=12m¯v2=32kTor √¯v2=vrms=√3kTm

- T=¯mv23k,where k is the Boltzmann constant and m is the mass of a helium atom.

4. Plug the known values into the equations and solve for the unknowns. m=molarmassnumberofatomspermole=4.0026×10−3kg/mole6.02×1023mol=6.65×10−27kg

Discussion

This temperature is much higher than atmospheric temperature, which is approximately 250 K (−25oC or −10oF) at high altitude. Very few helium atoms are left in the atmosphere, but there were many when the atmosphere was formed. The reason for the loss of helium atoms is that there are a small number of helium atoms with speeds higher than Earth’s escape velocity even at normal temperatures. The speed of a helium atom changes from one instant to the next, so that at any instant, there is a small, but nonzero chance that the speed is greater than the escape speed and the molecule escapes from Earth’s gravitational pull. Heavier molecules, such as oxygen, nitrogen, and water (very little of which reach a very high altitude), have smaller rms speeds, and so it is much less likely that any of them will have speeds greater than the escape velocity. In fact, so few have speeds above the escape velocity that billions of years are required to lose significant amounts of the atmosphere. Figure shows the impact of a lack of an atmosphere on the Moon. Because the gravitational pull of the Moon is much weaker, it has lost almost its entire atmosphere. The comparison between Earth and the Moon is discussed in this chapter’s Problems and Exercises.

Check Your Understanding

If you consider a very small object such as a grain of pollen, in a gas, then the number of atoms and molecules striking its surface would also be relatively small. Would the grain of pollen experience any fluctuations in pressure due to statistical fluctuations in the number of gas atoms and molecules striking it in a given amount of time?

[Hide Solution]

Yes. Such fluctuations actually occur for a body of any size in a gas, but since the numbers of atoms and molecules are immense for macroscopic bodies, the fluctuations are a tiny percentage of the number of collisions, and the averages spoken of in this section vary imperceptibly. Roughly speaking the fluctuations are proportional to the inverse square root of the number of collisions, so for small bodies they can become significant. This was actually observed in the 19th century for pollen grains in water, and is known as the Brownian effect.

PhET Explorations: Gas Properties

Pump gas molecules into a box and see what happens as you change the volume, add or remove heat, change gravity, and more. Measure the temperature and pressure, and discover how the properties of the gas vary in relation to each other.

Summary

- Kinetic theory is the atomistic description of gases as well as liquids and solids.

- Kinetic theory models the properties of matter in terms of continuous random motion of atoms and molecules.

- The ideal gas law can also be expressed as PV=13Nm¯v2,where P is the pressure (average force per unit area), V is the volume of gas in the container, N is the number of molecules in the container, is the mass of a molecule, and ¯v2 is the average of the molecular speed squared.

- The temperature of gases is proportional to the average translational kinetic energy of atoms and molecules. ¯KE=12m¯v2=32kTor √¯v2=vrms=√3kTm.

- The motion of individual molecules in a gas is random in magnitude and direction. However, a gas of many molecules has a predictable distribution of molecular speeds, known as the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.