17.3: Sound Intensity and Sound Level

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define intensity, sound intensity, and sound pressure level.

- Calculate sound intensity levels in decibels (dB).

In a quiet forest, you can sometimes hear a single leaf fall to the ground. After settling into bed, you may hear your blood pulsing through your ears. But when a passing motorist has his stereo turned up, you cannot even hear what the person next to you in your car is saying. We are all very familiar with the loudness of sounds and aware that they are related to how energetically the source is vibrating. In cartoons depicting a screaming person (or an animal making a loud noise), the cartoonist often shows an open mouth with a vibrating uvula, the hanging tissue at the back of the mouth, to suggest a loud sound coming from the throat Figure 17.3.1. High noise exposure is hazardous to hearing, and it is common for musicians to have hearing losses that are sufficiently severe that they interfere with the musicians’ abilities to perform. The relevant physical quantity is sound intensity, a concept that is valid for all sounds whether or not they are in the audible range.

Intensity is defined to be the power per unit area carried by a wave. Power is the rate at which energy is transferred by the wave. In equation form, intensity I is

I=PA,

where P is the power through an area A. The SI unit for I is W/m2. The intensity of a sound wave is related to its amplitude squared by the following relationship:

I=(Δp)22ρvw.

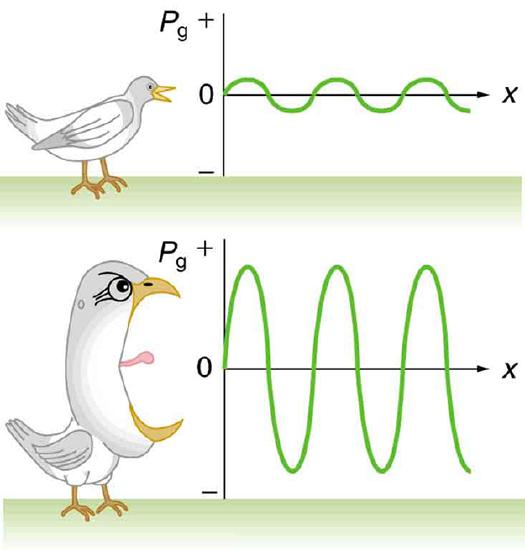

Here Δp is the pressure variation or pressure amplitude (half the difference between the maximum and minimum pressure in the sound wave) in units of pascals (Pa) or N/m2. (We are using a lower case p for pressure to distinguish it from power, denoted by P above.) The energy (as kinetic energy mv22) of an oscillating element of air due to a traveling sound wave is proportional to its amplitude squared. In this equation, ρ is the density of the material in which the sound wave travels, in units of kg/m3, and vw is the speed of sound in the medium, in units of m/s. The pressure variation is proportional to the amplitude of the oscillation, and so I varies as (Δp)2 (Figure 17.3.2). This relationship is consistent with the fact that the sound wave is produced by some vibration; the greater its pressure amplitude, the more the air is compressed in the sound it creates.

Sound intensity levels are quoted in decibels (dB) much more often than sound intensities in watts per meter squared. Decibels are the unit of choice in the scientific literature as well as in the popular media. The reasons for this choice of units are related to how we perceive sounds. How our ears perceive sound can be more accurately described by the logarithm of the intensity rather than directly to the intensity. The sound intensity level β in decibels of a sound having an intensity I in watts per meter squared is defined to be

β(dB)=10log10(II0),

where I0=10−12W/m2 is a reference intensity. In particular, I0 is the lowest or threshold intensity of sound a person with normal hearing can perceive at a frequency of 1000 Hz. Sound intensity level is not the same as intensity. Because β is defined in terms of a ratio, it is a unitless quantity telling you the level of the sound relative to a fixed standard (10−12W/m2, in this case). The units of decibels (dB) are used to indicate this ratio is multiplied by 10 in its definition. The bel, upon which the decibel is based, is named for Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone.

| Sound intensity level β (dB) | Intensity I(W?M2) | Example/effect |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1×10−12 | Threshold of hearing at 1000 Hz |

| 10 | 1×10−11 | Rustle of leaves |

| 20 | 1×10−10 | Whisper at 1 m distance |

| 30 | 1×10−9 | Quiet home |

| 40 | 1×10−8 | Average home |

| 50 | 1×10−7 | Average office, soft music |

| 60 | 1×10−6 | Normal conversation |

| 70 | 1×10−5 | Noisy office, busy traffic |

| 80 | 1×10−4 | Loud radio, classroom lecture |

| 90 | 1×10−3 | Inside a heavy truck; damage from prolonged exposure 1 |

| 100 | 1×10−2 | Noisy factory, siren at 30 m; damage from 8 h per day exposure |

| 110 | 1×10−1 | Damage from 30 min per day exposure |

| 120 | 1 | Loud rock concert, pneumatic chipper at 2 m; threshold of pain |

| 140 | 1×102 | Jet airplane at 30 m; severe pain, damage in seconds |

| 160 | 1×104 | Bursting of eardrums |

The decibel level of a sound having the threshold intensity of 10−12W/m2 is β=0dB, because log101=0. That is, the threshold of hearing is 0 decibels. Table 17.3.1 gives levels in decibels and intensities in watts per meter squared for some familiar sounds.

One of the more striking things about the intensities in Table 17.3.1 is that the intensity in watts per meter squared is quite small for most sounds. The ear is sensitive to as little as a trillionth of a watt per meter squared—even more impressive when you realize that the area of the eardrum is only about 1cm2, so that only 10−16 W falls on it at the threshold of hearing! Air molecules in a sound wave of this intensity vibrate over a distance of less than one molecular diameter, and the gauge pressures involved are less than 10−9 atm.

Another impressive feature of the sounds in Table 17.3.1 is their numerical range. Sound intensity varies by a factor of 1012 from threshold to a sound that causes damage in seconds. You are unaware of this tremendous range in sound intensity because how your ears respond can be described approximately as the logarithm of intensity. Thus, sound intensity levels in decibels fit your experience better than intensities in watts per meter squared. The decibel scale is also easier to relate to because most people are more accustomed to dealing with numbers such as 0, 53, or 120 than numbers such as 1.00×10−11.

One more observation readily verified by examining Table 17.3.1 or using Equation ??? is that each factor of 10 in intensity corresponds to 10 dB. For example, a 90 dB sound compared with a 60 dB sound is 30 dB greater, or three factors of 10 (that is, 103 times) as intense. Another example is that if one sound is 107 as intense as another, it is 70 dB higher. See Table 17.3.2.

| I2/I1 | β2/β1 |

|---|---|

| 2.0 | 3.0 dB |

| 5.0 | 7.0 dB |

| 10.0 | 10.0 dB |

Example 17.3.1: Calculating Sound Intensity Levels: Sound Waves

Calculate the sound intensity level in decibels for a sound wave traveling in air at 0oC and having a pressure amplitude of 0.656 Pa.

Strategy

We are given Δp, so we can calculate I using the equation I=(Δp)2/(2pvw)2. Using I, we can calculate β straight from its definition in β(dB)=10log10(I/I0).

Solution

(1) Identify knowns:

Sound travels at 331 m/s in air at 0oC.

Air has a density of 1.29kg/m3 at atmospheric pressure and 0oC.

(2) Enter these values and the pressure amplitude into I=(Δp)2/(2ρvw): I=(Δp)22ρvw=(0.656Pa)2(1.29kg/m3)(331m/s)=5.04×10−4W/m2

(3) Enter the value for I and the known value for I0 into β(dB=10log10(I/I0). Calculate to find the sound intensity level in decibels: 10log10(5.04×108)=10(8.70)dB=87dB.

Discussion

This 87 dB sound has an intensity five times as great as an 80 dB sound. So a factor of five in intensity corresponds to a difference of 7 dB in sound intensity level. This value is true for any intensities differing by a factor of five.

Example 17.3.2: Change Intensity Levels of a Sound: What Happens to the Decibel Level?

Show that if one sound is twice as intense as another, it has a sound level about 3 dB higher.

Strategy

You are given that the ratio of two intensities is 2 to 1, and are then asked to find the difference in their sound levels in decibels. You can solve this problem using of the properties of logarithms.

Solution

(1) Identify knowns:

The ratio of the two intensities is 2 to 1, or: I2I1=2.00.

We wish to show that the difference in sound levels is about 3 dB. That is, we want to show: β2−β1=3dB.

Note that: log10b−log10a=log10(ba).

(2) Use the definition of β to get: β2−β1=10log10(I2I1)=10log102.00=10(0.301)dB.

Discussion

This means that the two sound intensity levels differ by 3.01 dB, or about 3 dB, as advertised. Note that because only the ratio I2/I1 is given (and not the actual intensities), this result is true for any intensities that differ by a factor of two. For example, a 56.0 dB sound is twice as intense as a 53.0 dB sound, a 97.0 dB sound is half as intense as a 100 dB sound, and so on.

It should be noted at this point that there is another decibel scale in use, called the sound pressure level, based on the ratio of the pressure amplitude to a reference pressure. This scale is used particularly in applications where sound travels in water. It is beyond the scope of most introductory texts to treat this scale because it is not commonly used for sounds in air, but it is important to note that very different decibel levels may be encountered when sound pressure levels are quoted. For example, ocean noise pollution produced by ships may be as great as 200 dB expressed in the sound pressure level, where the more familiar sound intensity level we use here would be something under 140 dB for the same sound.

TAKE-HOME INVESTIGATION: FEELING SOUND

Find a CD player and a CD that has rock music. Place the player on a light table, insert the CD into the player, and start playing the CD. Place your hand gently on the table next to the speakers. Increase the volume and note the level when the table just begins to vibrate as the rock music plays. Increase the reading on the volume control until it doubles. What has happened to the vibrations?

Exercise 17.3.1

Describe how amplitude is related to the loudness of a sound.

- Answer

-

Amplitude is directly proportional to the experience of loudness. As amplitude increases, loudness increases

Exercise 17.3.2

Identify common sounds at the levels of 10 dB, 50 dB, and 100 dB.

- Answer

-

- 10 dB: Running fingers through your hair.

- 50 dB: Inside a quiet home with no television or radio.

- 100 dB: Take-off of a jet plane.

Summary

- Intensity is the same for a sound wave as was defined for all waves; it is I=PA, where P is the power crossing area A. The SI unit for I is watts per meter squared. The intensity of a sound wave is also related to the pressure amplitude Δp I=(Δp)22ρvw, where ρ is the density of the medium in which the sound wave travels and vw is the speed of sound in the medium.

- Sound intensity level in units of decibels (dB) is β(dB)=10log10(II0), where I0=10−12W/m2 is the threshold intensity of hearing.

Footnotes

Several government agencies and health-related professional associations recommend that 85 dB not be exceeded for 8-hour daily exposures in the absence of hearing protection.

Glossary

- intensity

- the power per unit area carried by a wave

- sound intensity level

- a unitless quantity telling you the level of the sound relative to a fixed standard

- sound pressure level

- the ratio of the pressure amplitude to a reference pressure