6.5: Equilibrium Torque and Tension in the Bicep*

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Torque about the Elbow

So far we have used lever concepts and static equilibrium to solve for the forces in our forearm example. To gain a deeper understanding of why and how the effort and load forces depend on the effort arm and load arm distances, we need to study the concept of torque. We have already decided that the weight of the ball was pulling the forearm down and trying to rotate it around the elbow joint. When a force tends to start or stop rotating an object then we say the force is causing a torque ( ) . In our example, the weight of the ball is causing a torque on the forearm with the elbow joint as the pivot. The size of a torque depends on several things, including the distance from the pivot point to the force that is causing the torque.

) . In our example, the weight of the ball is causing a torque on the forearm with the elbow joint as the pivot. The size of a torque depends on several things, including the distance from the pivot point to the force that is causing the torque.

Reinforcement Activity

The torque caused by a force depends on the distance that force acts from the pivot point. To feel this effect for yourself, try this:

Open a door by pushing perpendicular to the door near the handle, which is far from the pivot point at the hinges.

Now apply the same force perpendicular to the door, but right next to the hinges. Does the door open as easily as before, or did you have to push with greater force to make the door rotate?

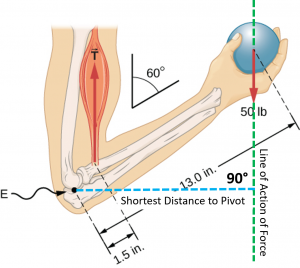

One method to account for the effect of the distance to pivot when calculating the size of a torque you can first draw the line of action of the force, which just means to extend a line from both ends of the force arrow (vector) in both directions. Next you draw the shortest line that you can from the pivot point to the line of action of the force. This shortest line and the line of action of the force will always be at 90° to each other, so the shortest line is called the perpendicular distance ( ). The perpendicular distance is also sometimes called the lever arm or moment arm or torque arm. We can draw these lines for our example problem:

). The perpendicular distance is also sometimes called the lever arm or moment arm or torque arm. We can draw these lines for our example problem:

Diagram of the flexed arm showing the line of action of the gravitational force and the perpendicular distance from the pivot to the line of action. Image adapted from Openstax University Physics.

Finally, we can calculate the torque by multiplying the size of the force by the length of the lever arm ( ) and that’s it, you get the torque. In symbol form it looks like this:

) and that’s it, you get the torque. In symbol form it looks like this:

(1)

Reinforcement Activity

If you hold your 0.65 m arm out horizontally with a 12 lb weight in your hand, what is the torque about your shoulder joint caused by the weight? Hint: If your arm is horizontal, and the weight points straight down, then what is the perpendicular distance from the joint to the weight?

After you have an answer, convert it from N·m to ft·lbs by using conversion factors between Newtons and pounds and feet and meters.

Rotational Equilibrium

The only time a torque won’t cause an object to start or stop rotating is when it’s cancelled out by other torques. This is exactly what is happening in our example problem, the torque caused by the bicep is counteracting the torque caused by the weight of the ball. When the torques cancel in this way, so that the net torque on the object is zero, the object is said to be in rotational equilibrium. In our example, the forearm is not starting to rotate (or stopping). Therefore the forearm is in rotational equilibrium so the net torque must be zero and that fact will allow us to find the bicep muscle tension. We have already stated that the forearm was not moving at all and that the net force so we can say the system is static equilibrium.

For an object to be in static equilibrium both the rotational and translational (linear) equilibrium conditions must be met. Writing these conditions on the torque and force in symbol form we have:

(2)

AND

(3)

Bicep Tension

The torques due to the bicep tension and the ball weight are trying to rotate the elbow in opposite directions, so if the forearm is in static equilibrium the two torques are equal in size they will cancel out and the net torque will be zero.

Looking at our equation for torque, we see that it only depends on the size of the force and the lever arm. That means that if the perpendicular distance to the bicep tension were 10x smaller than the distance to the center of the ball, the bicep tension force will have to be 10x times bigger than the weight of the ball in order to cause the same size torque and maintain rotational equilibrium. To find the bicep tension all we need to do now is determine how many times bigger the is the lever arm for the weight compared to the lever arm for the tension.

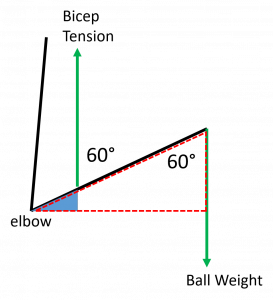

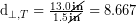

You might be thinking, but we can’t use this method, we don’t know the perpendicular lengths, they aren’t given, we only have the full distances from pivot to ball and pivot to bicep attachment. Don’t worry, if we draw a stick figure diagram we can see two triangles formed by the force action lines, the forearm and the perpendicular distances. The dashed (red) and solid (blue) triangles are similar triangles, which means that their respective sides have the same ratios of lengths.

Diagram of the forearm as a lever, showing the similar triangles formed by parts of the forearm as it moves from 90 degrees to 60 degrees from horizontal. The hypotenuse (long side) of the smaller blue triangle is the effort arm and the hypotenuse of the larger dashed red triangle is the load arm. The vertical sides of the triangles are the distances moved by the effort (blue) and the load (dashed red)

The lengths of the long sides of the triangles are 13.0 in and 1.5 in. Taking the ratio (dividing 13.0 by 1.5) we find that 13.0 in is 8.667x longer than 1.5 in. The bottom side of the small (solid) triangle must also be 8.667x smaller than the bottom side of the big one (dashed). That means that the lever arm for the bicep is 8.667x smaller than for the weight and so we know the bicep tension must be 8.667x bigger than the weight of the ball to maintain rotational equilibrium.

The ball weight is 50 lbs, so the bicep tension must be:

We’ve done it! Our result of 433 lbs seems surprisingly large, but we will see that forces even larger than this are common in the muscles, joints, and tendons of the body.

Symbol Form

Do you want to see everything we just did to calculate the tension in symbol form? Well, here you go:

The size of the torque due to the ball weight should be the tension multiplied by perpendicular distance to the ball:

The size of the torque due to the bicep tension should be the tension multiplied by perpendicular distance to the bicep attachment:

In order for net torque to be zero, these toques must be equal in size:

We want the tension, so we divide both sides by  :

:

From the similar triangles we know that the ratio of perpendicular distances is the same as the ratio of the triangles’ long sides:

Finally we find the tension: