9.8: Current

- Page ID

- 46936

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Define electric current, ampere, and drift velocity

- Describe the direction of charge flow in conventional current.

Electric Current

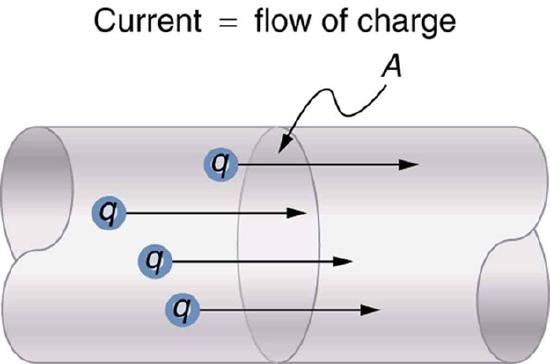

Electric current is defined to be the rate at which charge flows. A large current, such as that used to start a truck engine, moves a large amount of charge in a small time, whereas a small current, such as that used to operate a hand-held calculator, moves a small amount of charge over a long period of time. In equation form, electric current \(I\) is defined to be

\[I=\frac{\Delta Q}{\Delta t}, \nonumber \]

where \(\Delta Q\) is the amount of charge passing through a given area in time \(\Delta t\). (As in previous chapters, initial time is often taken to be zero, in which case \(\Delta t=t\).) (See Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).) The SI unit for current is the ampere (A), named for the French physicist André-Marie Ampère (1775–1836). Since \(I=\Delta Q / \Delta t\), we see that an ampere is one coulomb per second:

\[1 \mathrm{~A}=1 \ \mathrm{C} / \mathrm{s} \nonumber \]

Not only are fuses and circuit breakers rated in amperes (or amps), so are many electrical appliances.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Calculating Currents: Current in a Truck Battery and a Handheld Calculator

(a) What is the current involved when a truck battery sets in motion 720 C of charge in 4.00 s while starting an engine? (b) How long does it take 1.00 C of charge to flow through a handheld calculator if a 0.300-mA current is flowing?

Strategy

We can use the definition of current in the equation \(I=\Delta Q / \Delta t\) to find the current in part (a), since charge and time are given. In part (b), we rearrange the definition of current and use the given values of charge and current to find the time required.

Solution for (a)

Entering the given values for charge and time into the definition of current gives

\[\begin{aligned}

I &=\frac{\Delta Q}{\Delta t}=\frac{720 \mathrm{C}}{4.00 \mathrm{~s}}=180 \mathrm{C} / \mathrm{s} \\

&=180 \mathrm{~A} .

\end{aligned} \nonumber\]

Discussion for (a)

This large value for current illustrates the fact that a large charge is moved in a small amount of time. The currents in these “starter motors” are fairly large because large frictional forces need to be overcome when setting something in motion.

Solution for (b)

Solving the relationship \(I=\Delta Q / \Delta t\) for time \(\Delta t\), and entering the known values for charge and current gives

\[\begin{aligned}

\Delta t &=\frac{\Delta Q}{I}=\frac{1.00 \mathrm{C}}{0.300 \times 10^{-3} \mathrm{C} / \mathrm{s}} \\

&=3.33 \times 10^{3} \mathrm{~s}.

\end{aligned} \nonumber\]

Discussion for (b)

This time is slightly less than an hour. The small current used by the hand-held calculator takes a much longer time to move a smaller charge than the large current of the truck starter. So why can we operate our calculators only seconds after turning them on? It’s because calculators require very little energy. Such small current and energy demands allow handheld calculators to operate from solar cells or to get many hours of use out of small batteries. Remember, calculators do not have moving parts in the same way that a truck engine has with cylinders and pistons, so the technology requires smaller currents.

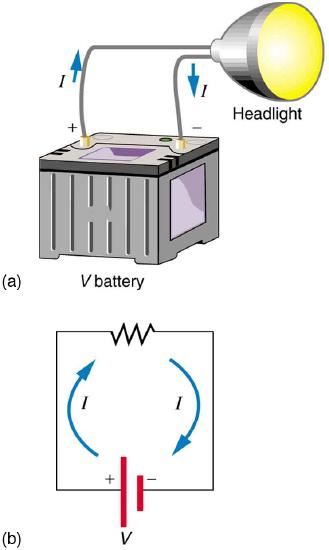

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows a simple circuit and the standard schematic representation of a battery, conducting path, and load (a resistor). Schematics are very useful in visualizing the main features of a circuit. A single schematic can represent a wide variety of situations. The schematic in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)(b), for example, can represent anything from a truck battery connected to a headlight lighting the street in front of the truck to a small battery connected to a penlight lighting a keyhole in a door. Such schematics are useful because the analysis is the same for a wide variety of situations. We need to understand a few schematics to apply the concepts and analysis to many more situations.

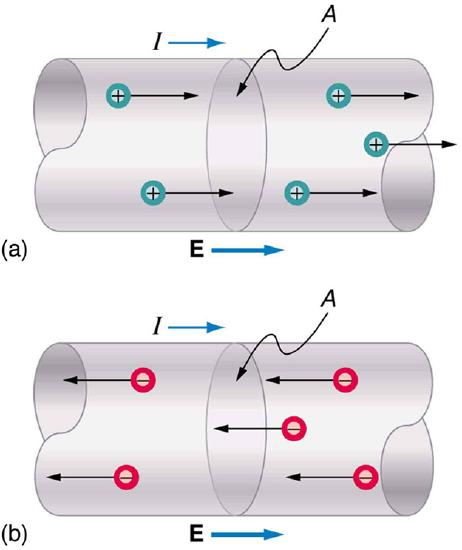

Note that the direction of current flow in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) is from positive to negative. The direction of conventional current is the direction that positive charge would flow. Depending on the situation, positive charges, negative charges, or both may move. In metal wires, for example, current is carried by electrons—that is, negative charges move. In ionic solutions, such as salt water, both positive and negative charges move. This is also true in nerve cells. A Van de Graaff generator used for nuclear research can produce a current of pure positive charges, such as protons. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) illustrates the movement of charged particles that compose a current. The fact that conventional current is taken to be in the direction that positive charge would flow can be traced back to American politician and scientist Benjamin Franklin in the 1700s. He named the type of charge associated with electrons negative, long before they were known to carry current in so many situations. Franklin, in fact, was totally unaware of the small-scale structure of electricity.

It is important to realize that there is an electric field in conductors responsible for producing the current, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). Unlike static electricity, where a conductor in equilibrium cannot have an electric field in it, conductors carrying a current have an electric field and are not in static equilibrium. An electric field is needed to supply energy to move the charges.

MAKING CONNECTIONS: TAKE-HOME INVESTIGATION—ELECTRIC CURRENT ILLUSTRATION

Find a straw and little peas that can move freely in the straw. Place the straw flat on a table and fill the straw with peas. When you pop one pea in at one end, a different pea should pop out the other end. This demonstration is an analogy for an electric current. Identify what compares to the electrons and what compares to the supply of energy. What other analogies can you find for an electric current?

Note that the flow of peas is based on the peas physically bumping into each other; electrons flow due to mutually repulsive electrostatic forces.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Calculating the Number of Electrons that Move through a Calculator

If the 0.300-mA current through the calculator mentioned in the Example \(\PageIndex{1}\) is carried by electrons, how many electrons per second pass through it?

Strategy

The current calculated in the previous example was defined for the flow of positive charge. For electrons, the magnitude is the same, but the sign is opposite, \(I_{\text {electrons }}=-0.300 \times 10^{-3} \mathrm{C} / \mathrm{s}\). Since each electron \(\left(e^{-}\right)\) has a charge of \(-1.60 \times 10^{-19} \ \mathrm{C}\), we can convert the current in coulombs per second to electrons per second.

Solution

Starting with the definition of current, we have

\[I_{\text {electrons }}=\frac{\Delta Q_{\text {electrons }}}{\Delta t}=\frac{-0.300 \times 10^{-3} \mathrm{C}}{\mathrm{s}}. \nonumber\]

We divide this by the charge per electron, so that

\[\begin{aligned}

\frac{e^{-}}{\mathrm{s}} &=\frac{-0.300 \times 10^{-3} \mathrm{C}}{\mathrm{s}} \times \frac{1 e^{-}}{-1.60 \times 10^{-19} \mathrm{C}} \\

&=1.88 \times 10^{15} \frac{e^{-}}{\mathrm{s}}.

\end{aligned} \nonumber\]

Discussion

There are so many charged particles moving, even in small currents, that individual charges are not noticed, just as individual water molecules are not noticed in water flow. Even more amazing is that they do not always keep moving forward like soldiers in a parade. Rather they are like a crowd of people with movement in different directions but a general trend to move forward. There are lots of collisions with atoms in the metal wire and, of course, with other electrons.

Section Summary

- Electric current \(I\) is the rate at which charge flows, given by

\[I=\frac{\Delta Q}{\Delta t}, \nonumber\]

where \(\Delta Q\) is the amount of charge passing through an area in time \(\Delta t\). - The direction of conventional current is taken as the direction in which positive charge moves.

- The SI unit for current is the ampere (A), where \(1 \mathrm{~A}=1 \ \mathrm{C} / \mathrm{s} \).

- Current is the flow of free charges, such as electrons and ions.

Glossary

- electric current

- the rate at which charge flows, \(I=\Delta Q / \Delta t\)

- ampere

- (amp) the SI unit for current; 1 A = 1 C/s