11.4: The Electromagnetic Spectrum- an Overview

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

- List three “rules of thumb” that apply to the different frequencies along the electromagnetic spectrum.

- Explain why the higher the frequency, the shorter the wavelength of an electromagnetic wave.

- Draw a simplified electromagnetic spectrum, indicating the relative positions, frequencies, and spacing of the different types of radiation bands.

In this module we examine how electromagnetic waves are classified into categories such as radio, infrared, ultraviolet, and so on, so that we can understand some of their similarities as well as some of their differences. We will also find that there are many connections with previously discussed topics, such as wavelength and resonance. A brief overview of the production and utilization of electromagnetic waves is found in Table 11.4.1. Note that the vast majority of the different types of electromagnetic waves originate from atomic and/or molecular electron transitions—that is, from electrons changing their energy levels within atoms or molecules.

CONNECTIONS: WAVES

There are many types of waves, such as water waves and even earthquakes. Among the many shared attributes of waves are propagation speed, frequency, and wavelength. These are always related by the expression vW=fλ. This module concentrates on EM waves, but other modules contain examples of all of these characteristics for sound waves and submicroscopic particles.

As noted before, an electromagnetic wave has a frequency and a wavelength associated with it and travels at the speed of light, or c. The relationship among these wave characteristics can be described by vW=fλ, where vW is the propagation speed of the wave, f is the frequency, and λ is the wavelength. Here vW=c, so that for all electromagnetic waves,

c=fλ.

Thus, for all electromagnetic waves, the greater the frequency, the smaller the wavelength.

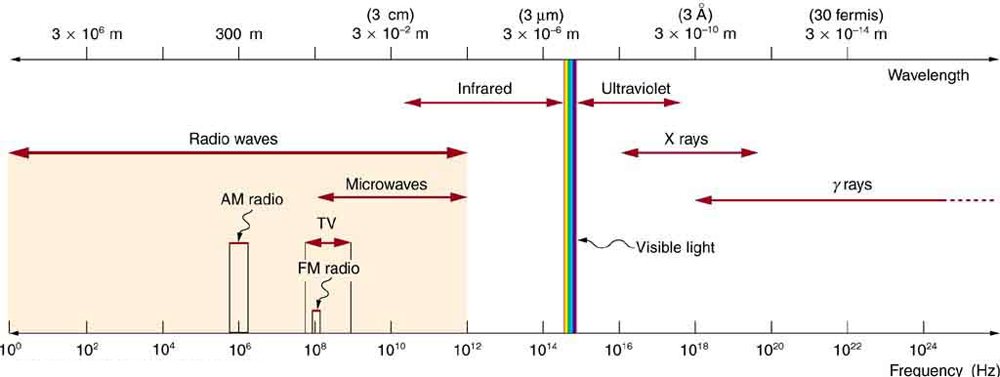

Figure 11.4.1 shows how the various types of electromagnetic waves are categorized according to their wavelengths and frequencies—that is, it shows the electromagnetic spectrum. Many of the characteristics of the various types of electromagnetic waves are related to their frequencies and wavelengths, as we shall see.

ELECTROMAGNETIC SPECTRUM: RULES OF THUMB

Three rules that apply to electromagnetic waves in general are as follows:

- High-frequency electromagnetic waves are more energetic and are more able to penetrate than low-frequency waves.

- High-frequency electromagnetic waves can carry more information per unit time than low-frequency waves.

- The shorter the wavelength of any electromagnetic wave probing a material, the smaller the detail it is possible to resolve.

Note that there are exceptions to these rules of thumb.

Transmission, Reflection, and Absorption

What happens when an electromagnetic wave impinges on a material? If the material is transparent to the particular frequency, then the wave can largely be transmitted. If the material is opaque to the frequency, then the wave can be totally reflected. The wave can also be absorbed by the material, indicating that there is some interaction between the wave and the material, such as the thermal agitation of molecules.

Of course it is possible to have partial transmission, reflection, and absorption. We normally associate these properties with visible light, but they do apply to all electromagnetic waves. What is not obvious is that something that is transparent to light may be opaque at other frequencies. For example, ordinary glass is transparent to visible light but largely opaque to ultraviolet radiation. Human skin is opaque to visible light—we cannot see through people—but transparent to X-rays.

Section Summary

- The relationship among the speed of propagation, wavelength, and frequency for any wave is given by vW=fλ, so that for electromagnetic waves,

c=fλ,

where f is the frequency, λ is the wavelength, and c is the speed of light. - The electromagnetic spectrum is separated into many categories and subcategories, based on the frequency and wavelength, source, and uses of the electromagnetic waves.

Glossary

- electromagnetic spectrum

- the full range of wavelengths or frequencies of electromagnetic radiation

- radio waves

- electromagnetic waves with wavelengths in the range from 1 mm to 100 km; they are produced by currents in wires and circuits and by astronomical phenomena

- microwaves

- electromagnetic waves with wavelengths in the range from 1 mm to 1 m; they can be produced by currents in macroscopic circuits and devices

- infrared radiation (IR)

- a region of the electromagnetic spectrum with a frequency range that extends from just below the red region of the visible light spectrum up to the microwave region, or from 0.74 μm to 300 μm

- ultraviolet radiation (UV)

- electromagnetic radiation in the range extending upward in frequency from violet light and overlapping with the lowest X-ray frequencies, with wavelengths from 400 nm down to about 10 nm

- visible light

- the narrow segment of the electromagnetic spectrum to which the normal human eye responds

- X-ray

- invisible, penetrating form of very high frequency electromagnetic radiation, overlapping both the ultraviolet range and the γ-ray range

- gamma ray

- (γ ray); extremely high frequency electromagnetic radiation emitted by the nucleus of an atom, either from natural nuclear decay or induced nuclear processes in nuclear reactors and weapons. The lower end of the γ-ray frequency range overlaps the upper end of the X-ray range, but γ rays can have the highest frequency of any electromagnetic radiation