14.6: Archimedes’ Principle and Buoyancy

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

- Define buoyant force

- State Archimedes’ principle

- Describe the relationship between density and Archimedes’ principle

When placed in a fluid, some objects float due to a buoyant force. Where does this buoyant force come from? Why is it that some things float and others do not? Do objects that sink get any support at all from the fluid? Is your body buoyed by the atmosphere, or are only helium balloons affected (Figure 14.6.1)?

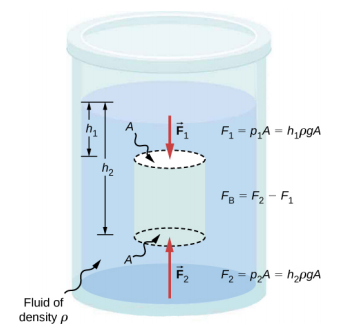

Answers to all these questions, and many others, are based on the fact that pressure increases with depth in a fluid. This means that the upward force on the bottom of an object in a fluid is greater than the downward force on top of the object. There is an upward force, or buoyant force, on any object in any fluid (Figure 14.6.2). If the buoyant force is greater than the object’s weight, the object rises to the surface and floats. If the buoyant force is less than the object’s weight, the object sinks. If the buoyant force equals the object’s weight, the object can remain suspended at its present depth. The buoyant force is always present, whether the object floats, sinks, or is suspended in a fluid.

The buoyant force is the upward force on any object in any fluid.

Archimedes’ Principle

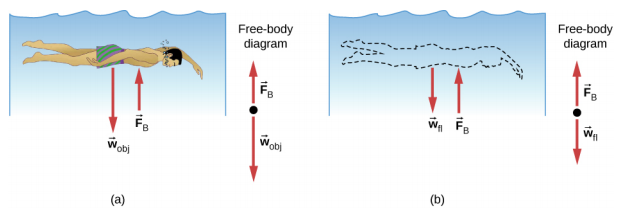

Just how large a force is buoyant force? To answer this question, think about what happens when a submerged object is removed from a fluid, as in Figure 14.6.3. If the object were not in the fluid, the space the object occupied would be filled by fluid having a weight wfl. This weight is supported by the surrounding fluid, so the buoyant force must equal wfl, the weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

The buoyant force on an object equals the weight of the fluid it displaces. In equation form, Archimedes’ principle is

FB=wfl,

where FB is the buoyant force and wfl is the weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

This principle is named after the Greek mathematician and inventor Archimedes (ca. 287–212 BCE), who stated this principle long before concepts of force were well established.

Archimedes’ principle refers to the force of buoyancy that results when a body is submerged in a fluid, whether partially or wholly. The force that provides the pressure of a fluid acts on a body perpendicular to the surface of the body. In other words, the force due to the pressure at the bottom is pointed up, while at the top, the force due to the pressure is pointed down; the forces due to the pressures at the sides are pointing into the body.

Since the bottom of the body is at a greater depth than the top of the body, the pressure at the lower part of the body is higher than the pressure at the upper part, as shown in Figure 14.6.2. Therefore a net upward force acts on the body. This upward force is the force of buoyancy, or simply buoyancy.

The exclamation “Eureka” (meaning “I found it”) has often been credited to Archimedes as he made the discovery that would lead to Archimedes’ principle. Some say it all started in a bathtub. To read the story, explore Scientific American to learn more.

Density and Archimedes’ Principle

If you drop a lump of clay in water, it will sink. But if you mold the same lump of clay into the shape of a boat, it will float. Because of its shape, the clay boat displaces more water than the lump and experiences a greater buoyant force, even though its mass is the same. The same is true of steel ships.

The average density of an object is what ultimately determines whether it floats. If an object’s average density is less than that of the surrounding fluid, it will float. The reason is that the fluid, having a higher density, contains more mass and hence more weight in the same volume. The buoyant force, which equals the weight of the fluid displaced, is thus greater than the weight of the object. Likewise, an object denser than the fluid will sink.

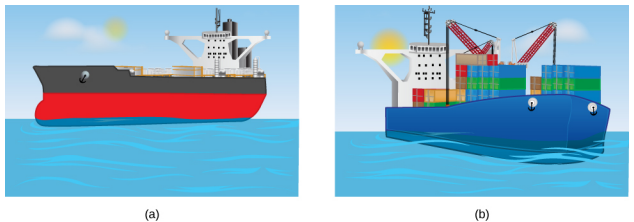

The extent to which a floating object is submerged depends on how the object’s density compares to the density of the fluid. In Figure 14.6.4, for example, the unloaded ship has a lower density and less of it is submerged compared with the same ship when loaded. We can derive a quantitative expression for the fraction submerged by considering density. The fraction submerged is the ratio of the volume submerged to the volume of the object, or

fractionsubmerged=VsubVobj=VflVobj.

The volume submerged equals the volume of fluid displaced, which we call Vfl. Now we can obtain the relationship between the densities by substituting ρ=mV into the expression. This gives

VflVobj=mflρflmobjρobj,

where ρobj is the average density of the object and ρfl is the density of the fluid. Since the object floats, its mass and that of the displaced fluid are equal, so they cancel from the equation, leaving

fractionsubmerged=ρobjρfl.

We can use this relationship to measure densities.

Suppose a 60.0-kg woman floats in fresh water with 97.0% of her volume submerged when her lungs are full of air. What is her average density?

Strategy

We can find the woman’s density by solving the equation

fractionsubmerged=ρobjρfl

for the density of the object. This yields

ρobj=ρperson=(fractionsubmerged)⋅ρfl.

We know both the fraction submerged and the density of water, so we can calculate the woman’s density.

Solution

Entering the known values into the expression for her density, we obtain

ρperson=0.970⋅103kg/m3=970kg/m3.

Significance

The woman’s density is less than the fluid density. We expect this because she floats.

Numerous lower-density objects or substances float in higher-density fluids: oil on water, a hot-air balloon in the atmosphere, a bit of cork in wine, an iceberg in salt water, and hot wax in a “lava lamp,” to name a few. A less obvious example is mountain ranges floating on the higher-density crust and mantle beneath them. Even seemingly solid Earth has fluid characteristics.

Measuring Density

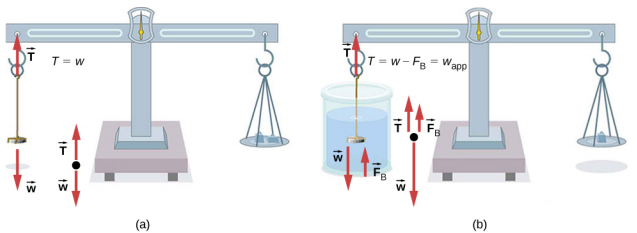

One of the most common techniques for determining density is shown in Figure 14.6.5.

An object, here a coin, is weighed in air and then weighed again while submerged in a liquid. The density of the coin, an indication of its authenticity, can be calculated if the fluid density is known. We can use this same technique to determine the density of the fluid if the density of the coin is known.

All of these calculations are based on Archimedes’ principle, which states that the buoyant force on the object equals the weight of the fluid displaced. This, in turn, means that the object appears to weigh less when submerged; we call this measurement the object’s apparent weight. The object suffers an apparent weight loss equal to the weight of the fluid displaced. Alternatively, on balances that measure mass, the object suffers an apparent mass loss equal to the mass of fluid displaced. That is, apparent weight loss equals weight of fluid displaced, or apparent mass loss equals mass of fluid displaced.