16.4: Wave Speed on a Stretched String

- Page ID

- 4071

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Determine the factors that affect the speed of a wave on a string

- Write a mathematical expression for the speed of a wave on a string and generalize these concepts for other media

The speed of a wave depends on the characteristics of the medium. For example, in the case of a guitar, the strings vibrate to produce the sound. The speed of the waves on the strings, and the wavelength, determine the frequency of the sound produced. The strings on a guitar have different thickness but may be made of similar material. They have different linear densities, where the linear density is defined as the mass per length,

\[\mu = \frac{\text{mass of string}}{\text{length of string}} = \frac{m}{l} \ldotp \label{16.7}\]

In this chapter, we consider only string with a constant linear density. If the linear density is constant, then the mass (\(\Delta m\)) of a small length of string (\(\Delta\)x) is \(\Delta m = \mu \Delta x\). For example, if the string has a length of 2.00 m and a mass of 0.06 kg, then the linear density is \(\mu = \frac{0.06\; kg}{2.00\; m}\) = 0.03 kg/m. If a 1.00-mm section is cut from the string, the mass of the 1.00-mm length is

\[ \Delta m = \mu \Delta x = (0.03\, kg/m)(0.001\, m) = 3.00 \times 10^{−5}\, kg. \nonumber\]

The guitar also has a method to change the tension of the strings. The tension of the strings is adjusted by turning spindles, called the tuning pegs, around which the strings are wrapped. For the guitar, the linear density of the string and the tension in the string determine the speed of the waves in the string and the frequency of the sound produced is proportional to the wave speed.

Wave Speed on a String under Tension

To see how the speed of a wave on a string depends on the tension and the linear density, consider a pulse sent down a taut string (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). When the taut string is at rest at the equilibrium position, the tension in the string \(F_T\) is constant. Consider a small element of the string with a mass equal to \(\Delta m = \mu \Delta x\). The mass element is at rest and in equilibrium and the force of tension of either side of the mass element is equal and opposite.

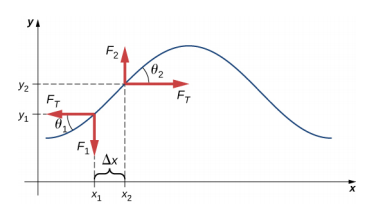

If you pluck a string under tension, a transverse wave moves in the positive x-direction, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). The mass element is small but is enlarged in the figure to make it visible. The small mass element oscillates perpendicular to the wave motion as a result of the restoring force provided by the string and does not move in the x-direction. The tension FT in the string, which acts in the positive and negative x-direction, is approximately constant and is independent of position and time.

Assume that the inclination of the displaced string with respect to the horizontal axis is small. The net force on the element of the string, acting parallel to the string, is the sum of the tension in the string and the restoring force. The x-components of the force of tension cancel, so the net force is equal to the sum of the y-components of the force. The magnitude of the x-component of the force is equal to the horizontal force of tension of the string \(F_T\) as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). To obtain the y-components of the force, note that tan \(\theta_{1} = − \frac{F_{1}}{F_{T}}\) and \(\tan \theta_{2} = \frac{F_{2}}{F_{T}}\). The \(\tan \theta\) is equal to the slope of a function at a point, which is equal to the partial derivative of y with respect to x at that point. Therefore, \(\frac{F_{1}}{F_{T}}\) is equal to the negative slope of the string at x1 and \(\frac{F_{2}}{F_{T}}\) is equal to the slope of the string at x2:

\[\frac{F_{1}}{F_{T}} = - \left(\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{x_{1}}\; and\; \frac{F_{2}}{F_{T}} = \left(\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{x_{2}} \ldotp\]

The net force is on the small mass element can be written as

\[F_{net} = F_{1} + F_{2} = F_{T} \Bigg[ \left(\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{x_{2}} - \left(\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{x_{1}} \Bigg] \ldotp\]

Using Newton’s second law, the net force is equal to the mass times the acceleration. The linear density of the string µ is the mass per length of the string, and the mass of the portion of the string is \(\mu \Delta\)x,

\[F_{T} \Bigg[ \left(\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{x_{2}} - \left(\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{x_{1}} \Bigg] = \Delta ma = \mu \Delta x \left(\frac{\partial^{2} y}{\partial t^{2}}\right) \ldotp\]

Dividing by FT\(\Delta\)x and taking the limit as \(\Delta\)x approaches zero,

\[\begin{split} \lim_{\Delta x \rightarrow 0} \frac{\Bigg[ \left(\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{x_{2}} - \left(\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial x}\right)_{x_{1}} \Bigg]}{\Delta x} & = \frac{\mu}{F_{T}} \frac{\partial^{2} y}{\partial t^{2}} \\ \frac{\partial^{2} y}{\partial x^{2}} & = \frac{\mu}{F_{T}} \frac{\partial^{2} y}{\partial t^{2}} \ldotp \end{split}\]

Recall that the linear wave equation is

\[\frac{\partial^{2} y(x,t)}{\partial x^{2}} = \frac{1}{v^{2}} \frac{\partial^{2} y(x,t)}{\partial t^{2}} \ldotp\]

Therefore,

\[\frac{1}{v^{2}} = \frac{\mu}{F_{T}} \ldotp\]

Solving for \(v\), we see that the speed of the wave on a string depends on the tension and the linear density

The speed of a pulse or wave on a string under tension can be found with the equation

\[|v| = \sqrt{\frac{F_{T}}{\mu}} \label{16.8}\]

where \(F_T\) is the tension in the string and \(µ\) is the mass per length of the string.

On a six-string guitar, the high E string has a linear density of \(\mu_{High\; E}\) = 3.09 x 10−4 kg/m and the low E string has a linear density of \(\mu_{Low\; E}\) = 5.78 x 10−3 kg/m. (a) If the high E string is plucked, producing a wave in the string, what is the speed of the wave if the tension of the string is 56.40 N? (b) The linear density of the low E string is approximately 20 times greater than that of the high E string. For waves to travel through the low E string at the same wave speed as the high E, would the tension need to be larger or smaller than the high E string? What would be the approximate tension? (c) Calculate the tension of the low E string needed for the same wave speed.

Strategy

- The speed of the wave can be found from the linear density and the tension \(v = \sqrt{\frac{F_{T}}{\mu}}\).

- From the equation v = \(\sqrt{\frac{F_{T}}{\mu}}\), if the linear density is increased by a factor of almost 20, the tension would need to be increased by a factor of 20.

- Knowing the velocity and the linear density, the velocity equation can be solved for the force of tension FT = \(\mu\)v2.

Solution

- Use the velocity equation to find the speed: $$v = \sqrt{\frac{F_{T}}{\mu}} = \sqrt{\frac{56.40\; N}{3.09 \times 10^{-4}\; kg/m}} = 427.23\; m/s \ldotp$$

- The tension would need to be increased by a factor of approximately 20. The tension would be slightly less than 1128 N.

- Use the velocity equation to find the actual tension: $$F_{T} = \mu v^{2} = (5.78 \times 10^{-3}\; kg/m)(427.23\; m/s)^{2} = 1055.00\; N \ldotp$$

- This solution is within 7% of the approximation.

Significance

The standard notes of the six string (high E, B, G, D, A, low E) are tuned to vibrate at the fundamental frequencies (329.63 Hz, 246.94 Hz, 196.00 Hz, 146.83 Hz, 110.00 Hz, and 82.41 Hz) when plucked. The frequencies depend on the speed of the waves on the string and the wavelength of the waves. The six strings have different linear densities and are “tuned” by changing the tensions in the strings. We will see in Interference of Waves that the wavelength depends on the length of the strings and the boundary conditions. To play notes other than the fundamental notes, the lengths of the strings are changed by pressing down on the strings.

The wave speed of a wave on a string depends on the tension and the linear mass density. If the tension is doubled, what happens to the speed of the waves on the string?

Speed of Compression Waves in a Fluid

The speed of a wave on a string depends on the square root of the tension divided by the mass per length, the linear density. In general, the speed of a wave through a medium depends on the elastic property of the medium and the inertial property of the medium.

\[|v| = \sqrt{\frac{elastic\; property}{inertial\; property}}\]

The elastic property describes the tendency of the particles of the medium to return to their initial position when perturbed. The inertial property describes the tendency of the particle to resist changes in velocity.

The speed of a longitudinal wave through a liquid or gas depends on the density of the fluid and the bulk modulus of the fluid,

\[v = \sqrt{\frac{\beta}{\rho}} \ldotp \label{16.9}\]

Here the bulk modulus is defined as Β = \(− \frac{\Delta P}{\frac{\Delta V}{V_{0}}}\), where \(\Delta\)P is the change in the pressure and the denominator is the ratio of the change in volume to the initial volume, and \(\rho \equiv \frac{m}{V}\) is the mass per unit volume. For example, sound is a mechanical wave that travels through a fluid or a solid. The speed of sound in air with an atmospheric pressure of 1.013 x 105 Pa and a temperature of 20°C is vs ≈ 343.00 m/s. Because the density depends on temperature, the speed of sound in air depends on the temperature of the air. This will be discussed in detail in Sound.