17.6: Sources of Musical Sound

- Page ID

- 4080

- Describe the resonant frequencies in instruments that can be modeled as a tube with symmetrical boundary conditions

- Describe the resonant frequencies in instruments that can be modeled as a tube with anti-symmetrical boundary conditions

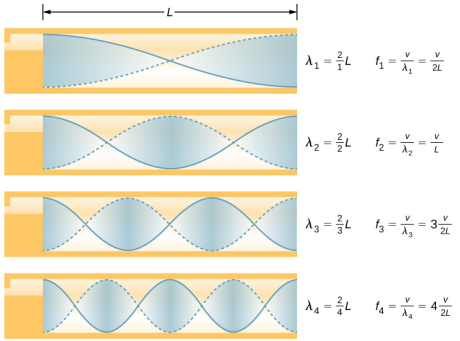

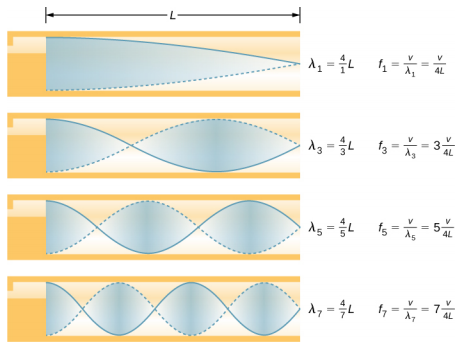

Some musical instruments, such as woodwinds, brass, and pipe organs, can be modeled as tubes with symmetrical boundary conditions, that is, either open at both ends or closed at both ends (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Other instruments can be modeled as tubes with anti-symmetrical boundary conditions, such as a tube with one end open and the other end closed (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Resonant frequencies are produced by longitudinal waves that travel down the tubes and interfere with the reflected waves traveling in the opposite direction. A pipe organ is manufactured with various tubes of fixed lengths to produce different frequencies. The waves are the result of compressed air allowed to expand in the tubes. Even in open tubes, some reflection occurs due to the constraints of the sides of the tubes and the atmospheric pressure outside the open tube.

The antinodes do not occur at the opening of the tube, but rather depend on the radius of the tube. The waves do not fully expand until they are outside the open end of a tube, and for a thin-walled tube, an end correction should be added. This end correction is approximately 0.6 times the radius of the tube and should be added to the length of the tube.

Players of instruments such as the flute or oboe vary the length of the tube by opening and closing finger holes. On a trombone, you change the tube length by using a sliding tube. Bugles have a fixed length and can produce only a limited range of frequencies.

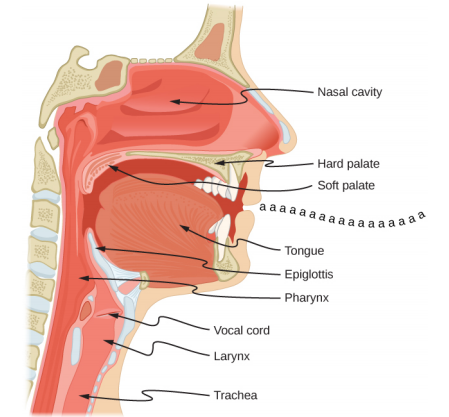

The fundamental and overtones can be present simultaneously in a variety of combinations. For example, middle C on a trumpet sounds distinctively different from middle C on a clarinet, although both instruments are modified versions of a tube closed at one end. The fundamental frequency is the same (and usually the most intense), but the overtones and their mix of intensities are different and subject to shading by the musician. This mix is what gives various musical instruments (and human voices) their distinctive characteristics, whether they have air columns, strings, sounding boxes, or drumheads. In fact, much of our speech is determined by shaping the cavity formed by the throat and mouth, and positioning the tongue to adjust the fundamental and combination of overtones. For example, simple resonant cavities can be made to resonate with the sound of the vowels (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). In boys at puberty, the larynx grows and the shape of the resonant cavity changes, giving rise to the difference in predominant frequencies in speech between men and women.

(a) What length should a tube closed at one end have on a day when the air temperature is 22.0 °C if its fundamental frequency is to be 128 Hz (C below middle C)? (b) What is the frequency of its fourth overtone?

Strategy

The length L can be found from the relationship fn = \(n \frac{v}{4L}\), but we first need to find the speed of sound v.

Solution

- Identify knowns: The fundamental frequency is 128 Hz, and the air temperature is 22.0 °C. Use fn = \(n \frac{v}{4L}\) to find the fundamental frequency (n = 1), $$f_{1} = \frac{v}{4L} \ldotp$$Solve this equation for length, $$L = \frac{v}{4f_{1}} \ldotp$$Find the speed of sound using v = (331 m/s)\(\sqrt{\frac{T}{273\; K}}\),$$v = (331\; m/s) \sqrt{\frac{295\; K}{273\; K}} = 344\; m/s \ldotp$$Enter the values of the speed of sound and frequency into the expression for L.$$L = \frac{v}{4f_{1}} = \frac{344\; m/s}{4(128\; Hz)} =0.672\; m$$

- Identify knowns: The first overtone has n = 3, the second overtone has n = 5, the third overtone has n = 7, and the fourth overtone has n = 9. Enter the value for the fourth overtone into fn = \(n \frac{v}{4L}\), $$f_{9} = 9 \frac{v}{4L} = 9 f_{1} = 1.15\; kHz \ldotp$$

Significance

Many wind instruments are modified tubes that have finger holes, valves, and other devices for changing the length of the resonating air column and hence, the frequency of the note played. Horns producing very low frequencies require tubes so long that they are coiled into loops. An example is the tuba. Whether an overtone occurs in a simple tube or a musical instrument depends on how it is stimulated to vibrate and the details of its shape. The trombone, for example, does not produce its fundamental frequency and only makes overtones.

If you have two tubes with the same fundamental frequency, but one is open at both ends and the other is closed at one end, they would sound different when played because they have different overtones. Middle C, for example, would sound richer played on an open tube, because it has even multiples of the fundamental as well as odd. A closed tube has only odd multiples.

Resonance

Resonance occurs in many different systems, including strings, air columns, and atoms. As we discussed in earlier chapters, resonance is the driven or forced oscillation of a system at its natural frequency. At resonance, energy is transferred rapidly to the oscillating system, and the amplitude of its oscillations grows until the system can no longer be described by Hooke’s law. An example of this is the distorted sound intentionally produced in certain types of rock music.

Wind instruments use resonance in air columns to amplify tones made by lips or vibrating reeds. Other instruments also use air resonance in clever ways to amplify sound. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows a violin and a guitar, both of which have sounding boxes but with different shapes, resulting in different overtone structures. The vibrating string creates a sound that resonates in the sounding box, greatly amplifying the sound and creating overtones that give the instrument its characteristic timbre. The more complex the shape of the sounding box, the greater its ability to resonate over a wide range of frequencies. The marimba, like the one shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\), uses pots or gourds below the wooden slats to amplify their tones. The resonance of the pot can be adjusted by adding water.

We have emphasized sound applications in our discussions of resonance and standing waves, but these ideas apply to any system that has wave characteristics. Vibrating strings, for example, are actually resonating and have fundamentals and overtones similar to those for air columns. More subtle are the resonances in atoms due to the wave character of their electrons. Their orbitals can be viewed as standing waves, which have a fundamental (ground state) and overtones (excited states). It is fascinating that wave characteristics apply to such a wide range of physical systems.