1.7: Huygens’s Principle

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe Huygens’s principle

- Use Huygens’s principle to explain the law of reflection

- Use Huygens’s principle to explain the law of refraction

- Use Huygens’s principle to explain diffraction

So far in this chapter, we have been discussing optical phenomena using the ray model of light. However, some phenomena require analysis and explanations based on the wave characteristics of light. This is particularly true when the wavelength is not negligible compared to the dimensions of an optical device, such as a slit in the case of diffraction. Huygens’s principle is an indispensable tool for this analysis.

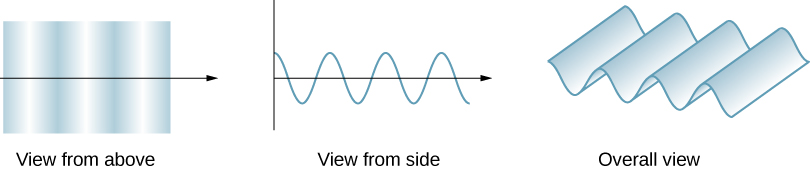

Figure 1.7.1 shows how a transverse wave looks as viewed from above and from the side. A light wave can be imagined to propagate like this, although we do not actually see it wiggling through space. From above, we view the wave fronts (or wave crests) as if we were looking down on ocean waves. The side view would be a graph of the electric or magnetic field. The view from above is perhaps more useful in developing concepts about wave optics.

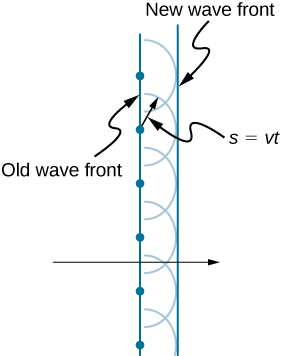

The Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) developed a useful technique for determining in detail how and where waves propagate. Starting from some known position, Huygens’s principle states that every point on a wave front is a source of wavelets that spread out in the forward direction at the same speed as the wave itself. The new wave front is tangent to all of the wavelets.

Figure 1.7.2 shows how Huygens’s principle is applied. A wave front is the long edge that moves, for example, with the crest or the trough. Each point on the wave front emits a semicircular wave that moves at the propagation speed v. We can draw these wavelets at a time t later, so that they have moved a distance s=vt. The new wave front is a plane tangent to the wavelets and is where we would expect the wave to be a time t later. Huygens’s principle works for all types of waves, including water waves, sound waves, and light waves. It is useful not only in describing how light waves propagate but also in explaining the laws of reflection and refraction. In addition, we will see that Huygens’s principle tells us how and where light rays interfere.

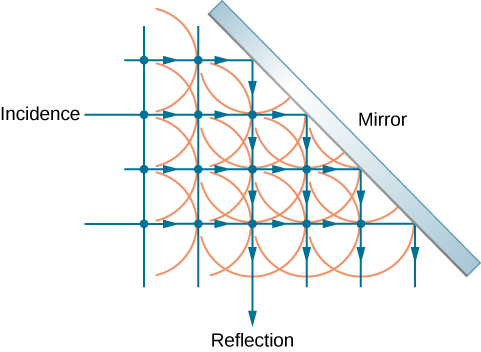

Reflection

Figure 1.7.3 shows how a mirror reflects an incoming wave at an angle equal to the incident angle, verifying the law of reflection. As the wave front strikes the mirror, wavelets are first emitted from the left part of the mirror and then from the right. The wavelets closer to the left have had time to travel farther, producing a wave front traveling in the direction shown.

Refraction

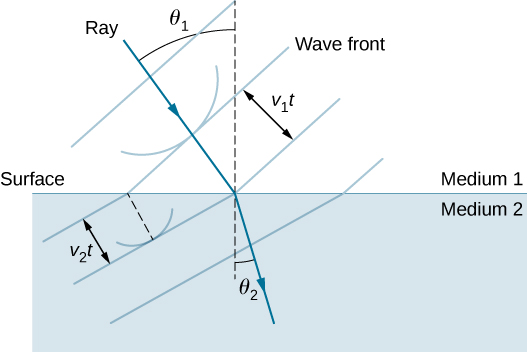

The law of refraction can be explained by applying Huygens’s principle to a wave front passing from one medium to another (Figure 1.7.4). Each wavelet in the figure was emitted when the wave front crossed the interface between the media. Since the speed of light is smaller in the second medium, the waves do not travel as far in a given time, and the new wave front changes direction as shown. This explains why a ray changes direction to become closer to the perpendicular when light slows down. Snell’s law can be derived from the geometry in Figure 1.7.5 (Example 1.7.1).

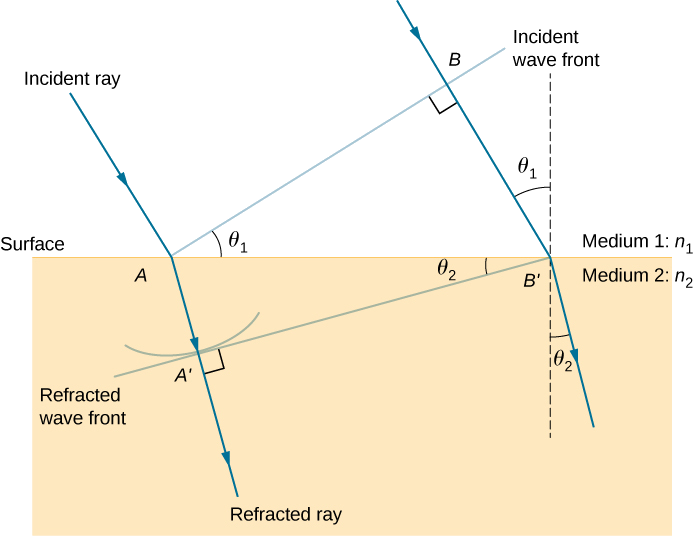

Example 1.7.1: Deriving the Law of Refraction

By examining the geometry of the wave fronts, derive the law of refraction.

Strategy

Consider Figure 1.7.5, which expands upon Figure 1.7.4. It shows the incident wave front just reaching the surface at point A, while point B is still well within medium 1. In the time Δt it takes for a wavelet from B to reach B′ on the surface at speed v1=c/n1, a wavelet from A travels into medium 2 a distance of AA′=v2Δt, where v2=c/n2. Note that in this example, v2 is slower than v1 because n1<n2.

Solution

The segment on the surface AB' is shared by both the triangle ABB' inside medium 1 and the triangle AA′B′ inside medium 2. Note that from the geometry, the angle ∠BAB' is equal to the angle of incidence, θ1. Similarly, ∠AB′A′ is θ2.

The length of AB' is given in two ways as

AB′=BB′sinθ1=AA′sinθ2.

Inverting the equation and substituting AA'=cΔt/n2 from above and similarly BB′=cΔt/n1, we obtain

sinθ1cΔt/n1=sinθ2cΔt/n2.

Cancellation of cΔt allows us to simplify this equation into the familiar form

n1sinθ1=n2sinθ2⏟Snell's law.

Significance

Although the law of refraction was established experimentally by Snell, its derivation here requires Huygens’s principle and the understanding that the speed of light is different in different media.

In Example 1.7.1, we had n1<n2. If n2 were decreased such that n1>n2 and the speed of light in medium 2 is faster than in medium 1, what would happen to the length of AA'? What would happen to the wave front A'B' and the direction of the refracted ray?

- Answer

-

AA′ becomes longer, A'B' tilts further away from the surface, and the refracted ray tilts away from the normal.

This applet by Walter Fendt shows an animation of reflection and refraction using Huygens’s wavelets while you control the parameters. Be sure to click on “Next step” to display the wavelets. You can see the reflected and refracted wave fronts forming.

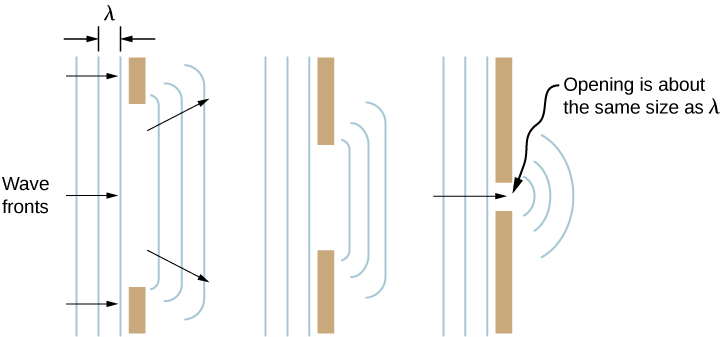

Diffraction

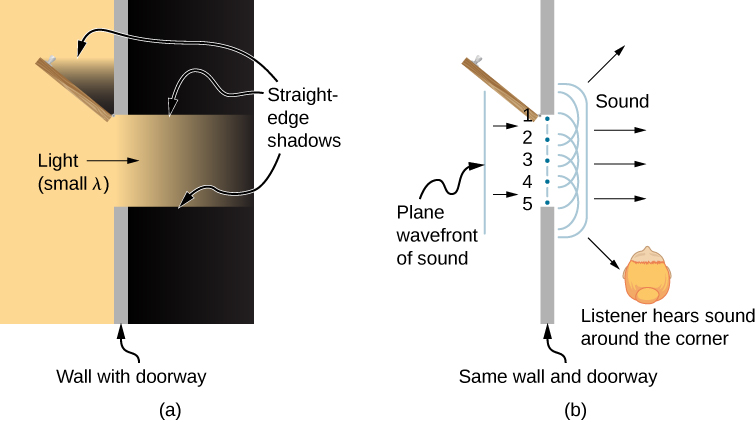

What happens when a wave passes through an opening, such as light shining through an open door into a dark room? For light, we observe a sharp shadow of the doorway on the floor of the room, and no visible light bends around corners into other parts of the room. When sound passes through a door, we hear it everywhere in the room and thus observe that sound spreads out when passing through such an opening (Figure 1.7.6). What is the difference between the behavior of sound waves and light waves in this case? The answer is that light has very short wavelengths and acts like a ray. Sound has wavelengths on the order of the size of the door and bends around corners (for frequency of 1000 Hz,

λ=cf=330m/s1000s−1=0.33m,

about three times smaller than the width of the doorway).

If we pass light through smaller openings such as slits, we can use Huygens’s principle to see that light bends as sound does (Figure 1.7.7). The bending of a wave around the edges of an opening or an obstacle is called diffraction. Diffraction is a wave characteristic and occurs for all types of waves. If diffraction is observed for some phenomenon, it is evidence that the phenomenon is a wave. Thus, the horizontal diffraction of the laser beam after it passes through the slits in Figure 1.7.7 is evidence that light is a wave.