1.5: Total Internal Reflection

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 65237

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the phenomenon of total internal reflection

- Describe the workings and uses of optical fibers

- Analyze the reason for the sparkle of diamonds

A good-quality mirror may reflect more than 90% of the light that falls on it, absorbing the rest. But it would be useful to have a mirror that reflects all of the light that falls on it. Interestingly, we can produce total reflection using an aspect of refraction.

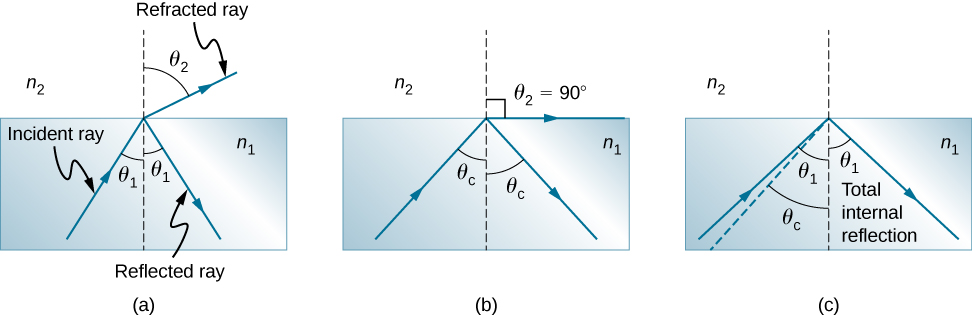

Consider what happens when a ray of light strikes the surface between two materials, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1a}\). Part of the light crosses the boundary and is refracted; the rest is reflected. If, as shown in the figure, the index of refraction for the second medium is less than for the first, the ray bends away from the perpendicular. (Since \(n_1>n_2\), the angle of refraction is greater than the angle of incidence—that is, \(θ_1>θ_2\).) Now imagine what happens as the incident angle increases. This causes \(θ_2\) to increase also. The largest the angle of refraction \(θ_2\) can be is \(90°\), as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1b}\).

The critical angle \(θ_c\) for a combination of materials is defined to be the incident angle \(θ_1\) that produces an angle of refraction of \(90°\). That is, \(θ_c\) is the incident angle for which \(θ_2=90°\). If the incident angle \(θ_1\) is greater than the critical angle, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1c}\), then all of the light is reflected back into medium 1, a condition called total internal reflection. (As Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows, the reflected rays obey the law of reflection so that the angle of reflection is equal to the angle of incidence in all three cases.)

Snell’s law states the relationship between angles and indices of refraction. It is given by

\[n_1\sin θ_1=n_2 \sin θ_2. \nonumber \]

When the incident angle equals the critical angle (\(θ_1=θ_c\)), the angle of refraction is \(90°\) (\(θ_2=90°\)). Noting that \(\sin 90°=1\), Snell’s law in this case becomes

\[n_1 \, \sin \, θ_1 = n_2. \nonumber \]

The critical angle \(θ_c\) for a given combination of materials is thus

\[ θ_c = \sin^{−1}\left(\frac{n_2}{n_1}\right)\label{critical} \]

for \(n_1>n_2\).

Total internal reflection occurs for any incident angle greater than the critical angle \(θ_c\), and it can only occur when the second medium has an index of refraction less than the first. Note that this equation is written for a light ray that travels in medium 1 and reflects from medium 2, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Determining a Critical Angle

What is the critical angle for light traveling in a polystyrene (a type of plastic) pipe surrounded by air? The index of refraction for polystyrene is 1.49.

Strategy

The index of refraction of air can be taken to be 1.00, as before. Thus, the condition that the second medium (air) has an index of refraction less than the first (plastic) is satisfied, and we can use the equation

\[θ_c=\sin^{−1}\left(\frac{n_2}{n_1}\right) \nonumber \]

to find the critical angle \(θ_c\), where \(n_2=1.00\) and \(n_1=1.49\).

Solution

Substituting the identified values gives

\[\begin{align} θ_c &= \sin^{−1}\left(\frac{1.00}{1.49}\right) \nonumber \\[4pt] &= \sin^{−1}(0.671) \nonumber \\[4pt] &= 42.2°. \nonumber \end{align} \nonumber \]

Significance

This result means that any ray of light inside the plastic that strikes the surface at an angle greater than 42.2° is totally reflected. This makes the inside surface of the clear plastic a perfect mirror for such rays, without any need for the silvering used on common mirrors. Different combinations of materials have different critical angles, but any combination with \(n_1>n_2\) can produce total internal reflection. The same calculation as made here shows that the critical angle for a ray going from water to air is 48.6°, whereas that from diamond to air is 24.4°, and that from flint glass to crown glass is 66.3°.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

At the surface between air and water, light rays can go from air to water and from water to air. For which ray is there no possibility of total internal reflection?

- Answer

-

air to water, because the condition that the second medium must have a smaller index of refraction is not satisfied

In the photo that opens this chapter, the image of a swimmer underwater is captured by a camera that is also underwater. The swimmer in the upper half of the photograph, apparently facing upward, is, in fact, a reflected image of the swimmer below. The circular ripple near the photograph’s center is actually on the water surface. The undisturbed water surrounding it makes a good reflecting surface when viewed from below, thanks to total internal reflection. However, at the very top edge of this photograph, rays from below strike the surface with incident angles less than the critical angle, allowing the camera to capture a view of activities on the pool deck above water.

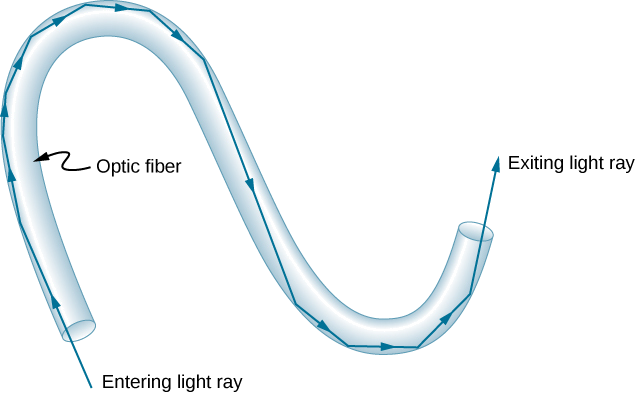

Fiber Optics: Endoscopes to Telephones

Fiber optics is one application of total internal reflection that is in wide use. In communications, it is used to transmit telephone, internet, and cable TV signals. Fiber optics employs the transmission of light down fibers of plastic or glass. Because the fibers are thin, light entering one is likely to strike the inside surface at an angle greater than the critical angle and, thus, be totally reflected (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). The index of refraction outside the fiber must be smaller than inside. In fact, most fibers have a varying refractive index to allow more light to be guided along the fiber through total internal refraction. Rays are reflected around corners as shown, making the fibers into tiny light pipes.

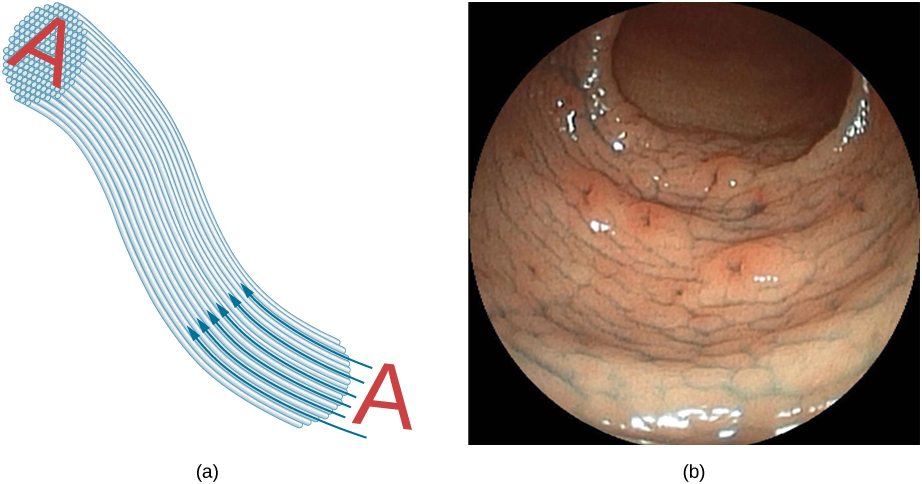

Bundles of fibers can be used to transmit an image without a lens, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). The output of a device called an endoscope is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1b}\). Endoscopes are used to explore the interior of the body through its natural orifices or minor incisions. Light is transmitted down one fiber bundle to illuminate internal parts, and the reflected light is transmitted back out through another bundle to be observed.

Fiber optics has revolutionized surgical techniques and observations within the body, with a host of medical diagnostic and therapeutic uses. Surgery can be performed, such as arthroscopic surgery on a knee or shoulder joint, employing cutting tools attached to and observed with the endoscope. Samples can also be obtained, such as by lassoing an intestinal polyp for external examination. The flexibility of the fiber optic bundle allows doctors to navigate it around small and difficult-to-reach regions in the body, such as the intestines, the heart, blood vessels, and joints. Transmission of an intense laser beam to burn away obstructing plaques in major arteries, as well as delivering light to activate chemotherapy drugs, are becoming commonplace. Optical fibers have in fact enabled microsurgery and remote surgery where the incisions are small and the surgeon’s fingers do not need to touch the diseased tissue.

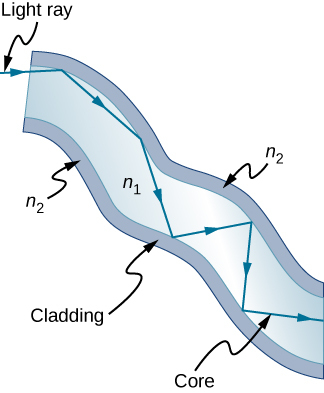

Optical fibers in bundles are surrounded by a cladding material that has a lower index of refraction than the core (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The cladding prevents light from being transmitted between fibers in a bundle. Without cladding, light could pass between fibers in contact, since their indices of refraction are identical. Since no light gets into the cladding (there is total internal reflection back into the core), none can be transmitted between clad fibers that are in contact with one another. Instead, the light is propagated along the length of the fiber, minimizing the loss of signal and ensuring that a quality image is formed at the other end. The cladding and an additional protective layer make optical fibers durable as well as flexible.

Special tiny lenses that can be attached to the ends of bundles of fibers have been designed and fabricated. Light emerging from a fiber bundle can be focused through such a lens, imaging a tiny spot. In some cases, the spot can be scanned, allowing quality imaging of a region inside the body. Special minute optical filters inserted at the end of the fiber bundle have the capacity to image the interior of organs located tens of microns below the surface without cutting the surface—an area known as nonintrusive diagnostics. This is particularly useful for determining the extent of cancers in the stomach and bowel.

In another type of application, optical fibers are commonly used to carry signals for telephone conversations and internet communications. Extensive optical fiber cables have been placed on the ocean floor and underground to enable optical communications. Optical fiber communication systems offer several advantages over electrical (copper)-based systems, particularly for long distances. The fibers can be made so transparent that light can travel many kilometers before it becomes dim enough to require amplification—much superior to copper conductors. This property of optical fibers is called low loss. Lasers emit light with characteristics that allow far more conversations in one fiber than are possible with electric signals on a single conductor. This property of optical fibers is called high bandwidth. Optical signals in one fiber do not produce undesirable effects in other adjacent fibers. This property of optical fibers is called reduced crosstalk. We shall explore the unique characteristics of laser radiation in a later chapter.

Corner Reflectors and Diamonds

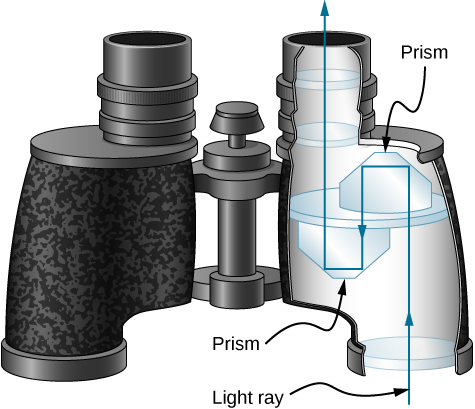

Corner reflectors are perfectly efficient when the conditions for total internal reflection are satisfied. With common materials, it is easy to obtain a critical angle that is less than 45°. One use of these perfect mirrors is in binoculars, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\). Another use is in periscopes found in submarines.

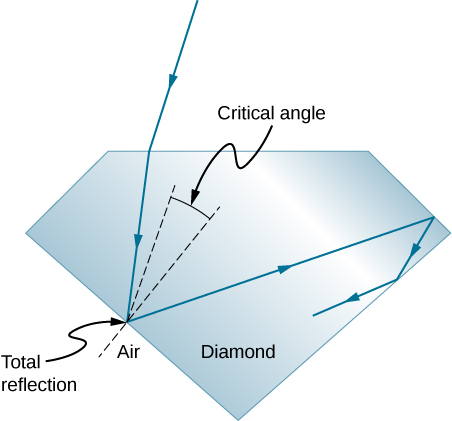

Total internal reflection, coupled with a large index of refraction, explains why diamonds sparkle more than other materials. The critical angle for a diamond-to-air surface is only 24.4°, so when light enters a diamond, it has trouble getting back out (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Although light freely enters the diamond, it can exit only if it makes an angle less than 24.4°. Facets on diamonds are specifically intended to make this unlikely. Good diamonds are very clear, so that the light makes many internal reflections and is concentrated before exiting—hence the bright sparkle. (Zircon is a natural gemstone that has an exceptionally large index of refraction, but it is not as large as diamond, so it is not as highly prized. Cubic zirconia is manufactured and has an even higher index of refraction (≈2.17), but it is still less than that of diamond.) The colors you see emerging from a clear diamond are not due to the diamond’s color, which is usually nearly colorless, but result from dispersion. Colored diamonds get their color from structural defects of the crystal lattice and the inclusion of minute quantities of graphite and other materials. The Argyle Mine in Western Australia produces around 90% of the world’s pink, red, champagne, and cognac diamonds, whereas around 50% of the world’s clear diamonds come from central and southern Africa.

Explore refraction and reflection of light between two media with different indices of refraction. Try to make the refracted ray disappear with total internal reflection. Use the protractor tool to measure the critical angle and compare with the prediction from Equation \ref{critical}.