11.4: The Law of Refraction

- Page ID

- 47076

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Determine the index of refraction, given the speed of light in a medium.

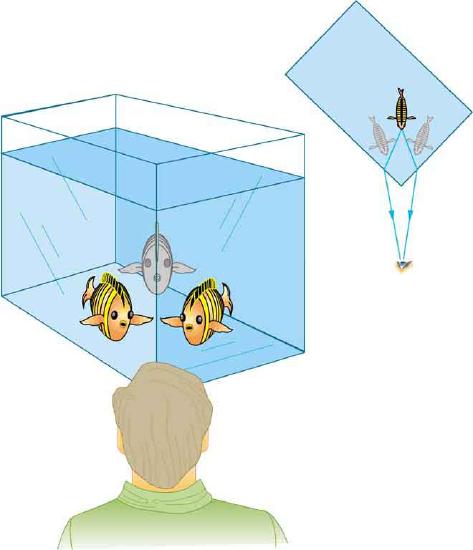

It is easy to notice some odd things when looking into a fish tank. For example, you may see the same fish appearing to be in two different places (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). This is because light coming from the fish to us changes direction when it leaves the tank, and in this case, it can travel two different paths to get to our eyes. The changing of a light ray’s direction (loosely called bending) when it passes through variations in matter is called refraction. Refraction is responsible for a tremendous range of optical phenomena, from the action of lenses to voice transmission through optical fibers.

Definition: REFRACTION

The changing of a light ray’s direction (loosely called bending) when it passes through variations in matter is called refraction.

SPEED OF LIGHT

The speed of light \(c\) not only affects refraction, it is one of the central concepts of Einstein’s theory of relativity. As the accuracy of the measurements of the speed of light were improved, \(c\) was found not to depend on the velocity of the source or the observer. However, the speed of light does vary in a precise manner with the material it traverses. These facts have far-reaching implications, as we will see in "Special Relativity." It makes connections between space and time and alters our expectations that all observers measure the same time for the same event, for example. The speed of light is so important that its value in a vacuum is one of the most fundamental constants in nature as well as being one of the four fundamental SI units.

Why does light change direction when passing from one material (medium) to another? It is because light changes speed when going from one material to another. So before we study the law of refraction, it is useful to discuss the speed of light and how it varies in different media.

The Speed of Light

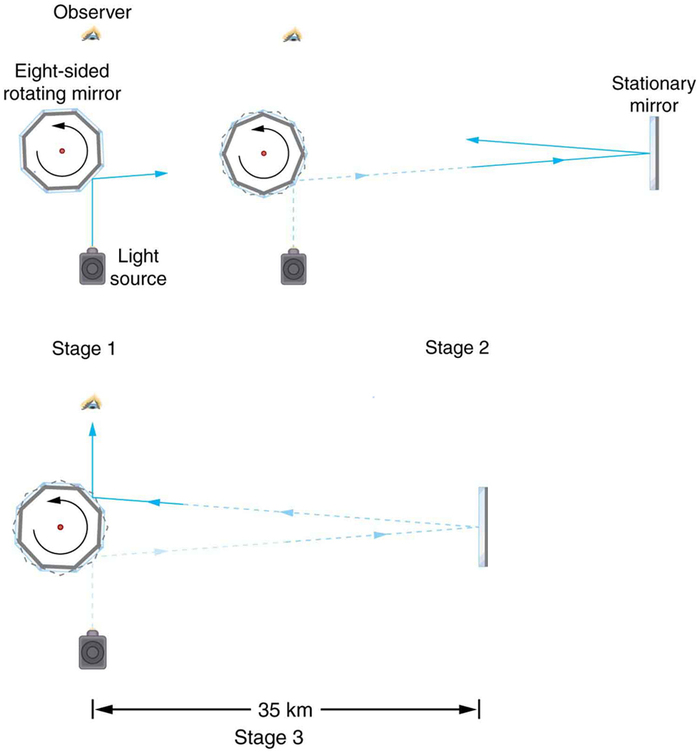

Early attempts to measure the speed of light, such as those made by Galileo, determined that light moved extremely fast, perhaps instantaneously. The first real evidence that light traveled at a finite speed came from the Danish astronomer Ole Roemer in the late 17th century. Roemer had noted that the average orbital period of one of Jupiter’s moons, as measured from Earth, varied depending on whether Earth was moving toward or away from Jupiter. He correctly concluded that the apparent change in period was due to the change in distance between Earth and Jupiter and the time it took light to travel this distance. From his 1676 data, a value of the speed of light was calculated to be \(2.26 \times 10^{8} m/s\) (only 25% different from today’s accepted value). In more recent times, physicists have measured the speed of light in numerous ways and with increasing accuracy. One particularly direct method, used in 1887 by the American physicist Albert Michelson (1852–1931), is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). Light reflected from a rotating set of mirrors was reflected from a stationary mirror 35 km away and returned to the rotating mirrors. The time for the light to travel can be determined by how fast the mirrors must rotate for the light to be returned to the observer’s eye.

The speed of light is now known to great precision. In fact, the speed of light in a vacuum \(c\) is so important that it is accepted as one of the basic physical quantities and has the fixed value.

VALUE OF THE SPEED OF LIGHT

\[\begin{align} c &\equiv 2.99792458 \times 10^{8} \\[5pt] &\sim 3.00 \times 10^{8} m/s \end{align}\]

The approximate value of \(3.00 \times 10^{8} m/s\) is used whenever three-digit accuracy is sufficient. The speed of light through matter is less than it is in a vacuum, because light interacts with atoms in a material. The speed of light depends strongly on the type of material, since its interaction with different atoms, crystal lattices, and other substructures varies.

Definition: INDEX OF REFRACTION

We define the index of refraction \(n\) of a material to be

\[n = \frac{c}{v}, \label{index}\]

where \(v\) is the observed speed of light in the material. Since the speed of light is always less than \(c\) in matter and equals \(c\) only in a vacuum, the index of refraction is always greater than or equal to one. That is, \(n \gt 1\).

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) gives the indices of refraction for some representative substances. The values are listed for a particular wavelength of light, because they vary slightly with wavelength. (This can have important effects, such as colors produced by a prism.) Note that for gases, \(n\) is close to 1.0. This seems reasonable, since atoms in gases are widely separated and light travels at \(c\) in the vacuum between atoms. It is common to take \(n = 1\) for gases unless great precision is needed. Although the speed of light \( v\) in a medium varies considerably from its value \( c\) in a vacuum, it is still a large speed.

| Medium | n |

|---|---|

| Gases at \(0ºC, 1 atm\) | |

| Air | 1.000293 |

| Carbon dioxide | 1.00045 |

| Hydrogen | 1.000139 |

| Oxygen | 1.000271 |

| Liquids at 20ºC | |

| Benzene | 1.501 |

| Carbon disulfide | 1.628 |

| Carbon tetrachloride | 1.461 |

| Ethanol | 1.361 |

| Glycerine | 1.473 |

| Water, fresh | 1.333 |

| Solids at 20ºC | |

| Diamond | 2.419 |

| Fluorite | 1.434 |

| Glass, crown | 1.52 |

| Glass, flint | 1.66 |

| Ice at 20ºC | 1.309 |

| Polystyrene | 1.49 |

| Plexiglas | 1.51 |

| Quartz, crystalline | 1.544 |

| Quartz, fused | 1.458 |

| Sodium chloride | 1.544 |

| Zircon | 1.923 |

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Speed of Light in Matter

Calculate the speed of light in zircon, a material used in jewelry to imitate diamond.

Strategy:

The speed of light in a material, \(v\), can be calculated from the index of refraction \(n\) of the material using the equation \(n = c/v\).

Solution

The equation for index of refraction (Equation \ref{index}) can be rearranged to determine \(v\)

\[v = \frac{c}{n}. \nonumber\]

The index of refraction for zircon is given as 1.923 in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\), and \(c\) is given in the equation for speed of light. Entering these values in the last expression gives

\[ \begin{align*} v &= \frac{3.00 \times 10^{8} m/s}{1.923} \\[5pt] &= 1.56 \times 10^{8} m/s. \end{align*}\]

Discussion:

This speed is slightly larger than half the speed of light in a vacuum and is still high compared with speeds we normally experience. The only substance listed in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) that has a greater index of refraction than zircon is diamond. We shall see later that the large index of refraction for zircon makes it sparkle more than glass, but less than diamond.

Law of Refraction

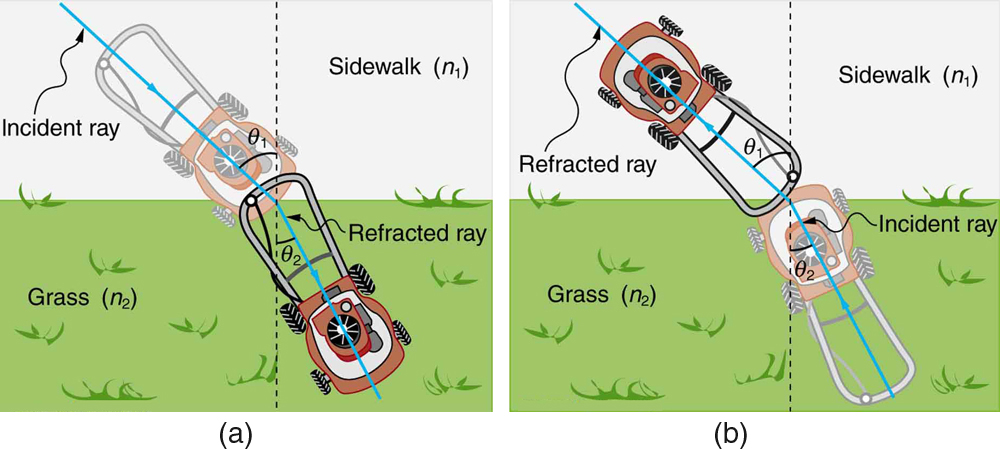

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows how a ray of light changes direction when it passes from one medium to another. As before, the angles are measured relative to a perpendicular to the surface at the point where the light ray crosses it. (Some of the incident light will be reflected from the surface, but for now we will concentrate on the light that is transmitted.) The change in direction of the light ray depends on how the speed of light changes. The change in the speed of light is related to the indices of refraction of the media involved. In the situations shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), medium 2 has a greater index of refraction than medium 1. This means that the speed of light is less in medium 2 than in medium 1. Note that as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3a}\), the direction of the ray moves closer to the perpendicular when it slows down. Conversely, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3b}\), the direction of the ray moves away from the perpendicular when it speeds up. The path is exactly reversible. In both cases, you can imagine what happens by thinking about pushing a lawn mower from a footpath onto grass, and vice versa. Going from the footpath to grass, the front wheels are slowed and pulled to the side as shown. This is the same change in direction as for light when it goes from a fast medium to a slow one. When going from the grass to the footpath, the front wheels can move faster and the mower changes direction as shown. This, too, is the same change in direction as for light going from slow to fast.

The amount that a light ray changes its direction depends both on the incident angle and the amount that the speed changes. For a ray at a given incident angle, a large change in speed causes a large change in direction, and thus a large change in angle.

TAKE-HOME EXPERIMENT: A BROKEN PENCIL

A classic observation of refraction occurs when a pencil is placed in a glass half filled with water. Do this and observe the shape of the pencil when you look at the pencil sideways, that is, through air, glass, water. Explain your observations. Draw ray diagrams for the situation.

Summary

- The changing of a light ray’s direction when it passes through variations in matter is called refraction.

- The speed of light in vacuuum \(c = 2.99792458 \times 10^{8} \sim 3.00 \times 10^{8} m/s\)

- Index of refraction \(n = \frac{c}{v}\), where \(v\) is the speed of light in the material, \(c\) is the speed of light in vacuum, and \(n\) is the index of refraction.

Glossary

- refraction

- changing of a light ray’s direction when it passes through variations in matter

- index of refraction

- for a material, the ratio of the speed of light in vacuum to that in the material

Contributors and Attributions

Paul Peter Urone (Professor Emeritus at California State University, Sacramento) and Roger Hinrichs (State University of New York, College at Oswego) with Contributing Authors: Kim Dirks (University of Auckland) and Manjula Sharma (University of Sydney). This work is licensed by OpenStax University Physics under a Creative Commons Attribution License (by 4.0).