10.5: Angular Momentum and Its Conservation

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the analogy between angular momentum and linear momentum.

- Observe the relationship between torque and angular momentum.

- Apply the law of conservation of angular momentum.

Why does Earth keep on spinning? What started it spinning to begin with? And how does an ice skater manage to spin faster and faster simply by pulling her arms in? Why does she not have to exert a torque to spin faster? Questions like these have answers based in angular momentum, the rotational analog to linear momentum.

By now the pattern is clear—every rotational phenomenon has a direct translational analog. It seems quite reasonable, then, to define angular momentum L as L=Iω

This equation is an analog to the definition of linear momentum as

p=mv

Units for linear momentum are kg⋅m/s, while units for angular momentum are kg⋅m/s2. As we would expect, an object that has a large moment of inertia I, such as Earth, has a very large angular momentum. An object that has a large angular velocity ω, such as a centrifuge, also has a rather large angular momentum.

Angular momentum is completely analogous to linear momentum, first presented in Uniform Circular Motion and Gravitation. It has the same implications in terms of carrying rotation forward, and it is conserved when the net external torque is zero. Angular momentum, like linear momentum, is also a property of the atoms and subatomic particles.

Example 10.5.1: Calculating Angular Momentum of the Earth

What is the angular momentum of the earth?

Strategy

No information is given in the statement of the problem; so we must look up pertinent data before we can calculate L=Iω First, the formula for the moment of inertia of a sphere is

I=2MR25

L=Iω=2MR2ω5.

Earth's mass M is 5.979×1024kg and its radius R is 6.376×106m. The Earth’s angular velocity ω is, of course, exactly one revolution per day, but we must covert ω to radians per second to do the calculation in SI units.

Solution

Substituting known information into the expression for L and converting ω to radians per second gives

L=0.4(5.979×1024kg)(6.376×106m)(1revd)

=9.72×1037kg⋅m2⋅rev/d

Substituting 2π for 1 rev and 8.64×104s for 1 day gives

L=(9.72×1037kg⋅m2)(2πrad/rev8.64×104s/d)(1rev/d)

=7.07×1033kg⋅m2/s.

Discussion

This number is large, demonstrating that Earth, as expected, has a tremendous angular momentum. The answer is approximate, because we have assumed a constant density for Earth in order to estimate its moment of inertia.

When you push a merry-go-round, spin a bike wheel, or open a door, you exert a torque. If the torque you exert is greater than opposing torques, then the rotation accelerates, and angular momentum increases. The greater the net torque, the more rapid the increase in L. The relationship between torque and angular momentum is

netτ=ΔLΔt.

This expression is exactly analogous to the relationship between force and linear momentum, F=Δp/Δt. The equation netτ=ΔL/Δt is very fundamental and broadly applicable. It is, in fact, the rotational form of Newton’s second law.

Example 10.5.1: Calculating the Torque Putting Angular Momentum Into a Lazy Susan

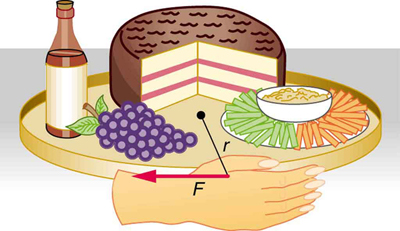

Figure 10.5.1 shows a Lazy Susan food tray being rotated by a person in quest of sustenance. Suppose the person exerts a 2.50 N force perpendicular to the lazy Susan’s 0.260-m radius for 0.150 s.

- What is the final angular momentum of the lazy Susan if it starts from rest, assuming friction is negligible?

- What is the final angular velocity of the lazy Susan, given that its mass is 4.00 kg and assuming its moment of inertia is that of a disk?

Figure 10.5.1: A partygoer exerts a torque on a lazy Susan to make it rotate. The equation netτ=ΔLΔt gives the relationship between torque and the angular momentum produced.

Strategy

We can find the angular momentum by solving netτ=ΔLΔt for ΔL, and using the given information to calculate the torque. The final angular momentum equals the change in angular momentum, because the lazy Susan starts from rest. That is, ΔL=L To find the final velocity, we must calculate ω from the definition of L in L=Iω.

Solution for (a)

Solving netτ=ΔLΔt for ΔL gives

ΔL=(netτ)Δt.

Because the force is perpendicular to r, we see that netτ=rF so that

L=rFΔt=(0.260m)(2.50N)(0.150s)

=9.75×10−2kg⋅m2/s.

Solution for (b)

The final angular velocity can be calculated from the definition of angular momentum,

L=Iω.

Solving for ω and substituting the formula for the moment of inertia of a disk into the resulting equation gives

ω=LI=L12MR2.

And substituting known values into the preceding equation yields

ω=9.75×10−2kg⋅m2/s(0.500)(4.00kg)(0.260m)=0.721rad/s.

Discussion

Note that the imparted angular momentum does not depend on any property of the object but only on torque and time. The final angular velocity is equivalent to one revolution in 8.71 s (determination of the time period is left as an exercise for the reader), which is about right for a lazy Susan.

Example 10.5.3: Calculating the Torque in a Kick

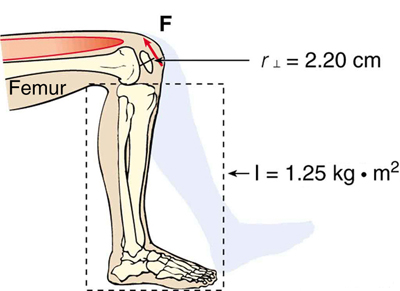

The person whose leg is shown in 10.5.1 kicks his leg by exerting a 2000-N force with his upper leg muscle. The effective perpendicular lever arm is 2.20 cm. Given the moment of inertia of the lower leg is 1.25kg⋅m2.

- find the angular acceleration of the leg.

- Neglecting the gravitational force, what is the rotational kinetic energy of the leg after it has rotated through 57.30 (1.00 rad)?

Strategy

The angular acceleration can be found using the rotational analog to Newton’s second law, or α=netτ/I. The moment of inertia I is given and the torque can be found easily from the given force and perpendicular lever arm. Once the angular acceleration α is known, the final angular velocity and rotational kinetic energy can be calculated.

Solution to (a)

From the rotational analog to Newton’s second law, the angular acceleration α is

α=netτI.

Because the force and the perpendicular lever arm are given and the leg is vertical so that its weight does not create a torque, the net torque is thus

netτ=r⊥F

=(0.0220m)(2000N)

=44.0N⋅m

Substituting this value for the torque and the given value for the moment of inertia into the expression for α gives

α=44.0N⋅m1.25kg⋅m2=35.2rad/s2

Solution to (b)

The final angular velocity can be calculated from the kinematic expression

ω2=ω20+2αθ

or

ω2=2αθ

because the initial angular velocity is zero. The kinetic energy of rotation is

KErot=12Iω2

so it is most convenient to use the value of ω2 just found and the given value for the moment of inertia. The kinetic energy is then

KErot=0.5(1.25kg⋅m2)(70.4rad2/s2)

=44J

Discussion

These values are reasonable for a person kicking his leg starting from the position shown. The weight of the leg can be neglected in part (a) because it exerts no torque when the center of gravity of the lower leg is directly beneath the pivot in the knee. In part (b), the force exerted by the upper leg is so large that its torque is much greater than that created by the weight of the lower leg as it rotates. The rotational kinetic energy given to the lower leg is enough that it could give a ball a significant velocity by transferring some of this energy in a kick.

Angular momentum, like energy and linear momentum, is conserved. This universally applicable law is another sign of underlying unity in physical laws. Angular momentum is conserved when net external torque is zero, just as linear momentum is conserved when the net external force is zero.

Conservation of Angular Momentum

We can now understand why Earth keeps on spinning. As we saw in the previous example, ΔL=(netτ)Δt. This equation means that, to change angular momentum, a torque must act over some period of time. Because Earth has a large angular momentum, a large torque acting over a long time is needed to change its rate of spin. So what external torques are there? Tidal friction exerts torque that is slowing Earth’s rotation, but tens of millions of years must pass before the change is very significant. Recent research indicates the length of the day was 18 h some 900 million years ago. Only the tides exert significant retarding torques on Earth, and so it will continue to spin, although ever more slowly, for many billions of years.

What we have here is, in fact, another conservation law. If the net torque is zero, then angular momentum is constant or conserved. We can see this rigorously by considering netτ=ΔLΔt for the situation in which the net torque is zero. In that case,

netτ=0

ΔLΔt=0.

If the change in angular momentum ΔL is zero, then the angular momentum is constant; thus,

L=constant(netτ=0)

L=L′(netτ=0).

These expressions are the law of conservation of angular momentum. Conservation laws are as scarce as they are important.

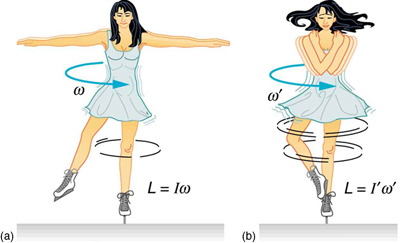

An example of conservation of angular momentum is seen in Figure 10.5.3, in which an ice skater is executing a spin. The net torque on her is very close to zero, because there is relatively little friction between her skates and the ice and because the friction is exerted very close to the pivot point. (Both F and τ are small, and so τ is negligibly small.) Consequently, she can spin for quite some time. She can do something else, too. She can increase her rate of spin by pulling her arms and legs in. Why does pulling her arms and legs in increase her rate of spin? The answer is that her angular momentum is constant, so that

L=L′.

Expressing this equation in terms of the moment of inertia,

Iω=I′ω′

where the primed quantities refer to conditions after she has pulled in her arms and reduced her moment of inertia. Because I′ is smaller, the angular velocity ω′ must increase to keep the angular momentum constant. The change can be dramatic, as the following example shows.

Example 10.5.4: Calculating the Angular Momentum of a Spinning Skater

Suppose an ice skater, such as the one in Figure 10.5.3, is spinning at 0.800 rev/ s with her arms extended. She has a moment of inertia of 2.34kg⋅m2 with her arms extended and of 0.363kg⋅m2 with her arms close to her body. (These moments of inertia are based on reasonable assumptions about a 60.0-kg skater.) (a) What is her angular velocity in revolutions per second after she pulls in her arms? (b) What is her rotational kinetic energy before and after she does this?

Strategy

In the first part of the problem, we are looking for the skater’s angular velocity ω′ after she has pulled in her arms. To find this quantity, we use the conservation of angular momentum and note that the moments of inertia and initial angular velocity are given. To find the initial and final kinetic energies, we use the definition of rotational kinetic energy given by

KErot=12Iω2

Solution for (a)

Because torque is negligible (as discussed above), the conservation of angular momentum given in Iω=I′ω′ is applicable. Thus,

L=L′

Solving for ω′ and substituting known values into the resulting equation gives

ω′=II′ω=(2.34kg⋅m20.363kg⋅m2)(0.800rev/s)

=5.16rev/s.

Solution for (b)

Rotational kinetic energy is given by

KErot=12Iω2

The initial value is found by substituting known values into the equation and converting the angular velocity to rad/s:

KErot=(0.5)(2.34kg⋅m2)((0.800rev/s)(2πrad/rev))2

=29.6J.

The final rotational kinetic energy is

KE′rot=12I′ω′2

Substituting known values into this equation gives

KE′rot=(0.5)(0.363kg⋅m2)[(5.16rev/s)((2πrad/rev)]2

=191J.

Discussion

In both parts, there is an impressive increase. First, the final angular velocity is large, although most world-class skaters can achieve spin rates about this great. Second, the final kinetic energy is much greater than the initial kinetic energy. The increase in rotational kinetic energy comes from work done by the skater in pulling in her arms. This work is internal work that depletes some of the skater’s food energy.

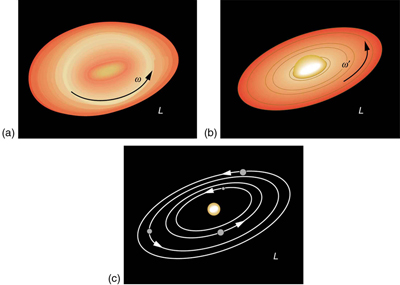

There are several other examples of objects that increase their rate of spin because something reduced their moment of inertia. Tornadoes are one example. Storm systems that create tornadoes are slowly rotating. When the radius of rotation narrows, even in a local region, angular velocity increases, sometimes to the furious level of a tornado. Earth is another example. Our planet was born from a huge cloud of gas and dust, the rotation of which came from turbulence in an even larger cloud. Gravitational forces caused the cloud to contract, and the rotation rate increased as a result (Figure 10.5.3).

Exercise 10.5.1: Check Your Undestanding

Is angular momentum completely analogous to linear momentum? What, if any, are their differences?

Solution

Yes, angular and linear momenta are completely analogous. While they are exact analogs they have different units and are not directly inter-convertible like forms of energy are.

Summary

- Every rotational phenomenon has a direct translational analog , likewise angular momentum L can be defined as L=Iω.

- This equation is an analog to the definition of linear momentum as p=mv. The relationship between torque and angular momentum is netτ=ΔL/Δt.

- Angular momentum, like energy and linear momentum, is conserved. This universally applicable law is another sign of underlying unity in physical laws. Angular momentum is conserved when net external torque is zero, just as linear momentum is conserved when the net external force is zero.

Glossary

- angular momentum

- the product of moment of inertia and angular velocity

- law of conservation of angular momentum

- angular momentum is conserved, i.e., the initial angular momentum is equal to the final angular momentum when no external torque is applied to the system