29.3: Photon Energies and the Electromagnetic Spectrum

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the relationship between the energy of a photon in joules or electron volts and its wavelength or frequency.

- Calculate the number of photons per second emitted by a monochromatic source of specific wavelength and power.

Ionizing Radiation

A photon is a quantum of EM radiation. Its energy is given by E=hf and is related to the frequency f and wavelength λ of the radiation by

E=hf=hcλ(energy of a photon)

where E is the energy of a single photon and c is the speed of light. When working with small systems, energy in eV is often useful. Note that Planck’s constant in these units is

h=4.14×10−15eV⋅s.

Since many wavelengths are stated in nanometers (nm), it is also useful to know that

hc=1240eV⋅nm.

These will make many calculations a little easier.

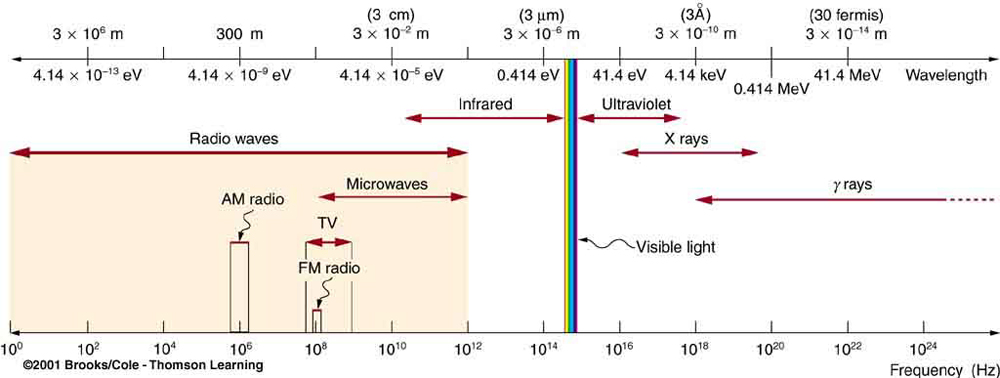

All EM radiation is composed of photons. Figure 29.3.1 shows various divisions of the EM spectrum plotted against wavelength, frequency, and photon energy. Previously in this book, photon characteristics were alluded to in the discussion of some of the characteristics of UV, x rays, and γ rays, the first of which start with frequencies just above violet in the visible spectrum. It was noted that these types of EM radiation have characteristics much different than visible light. We can now see that such properties arise because photon energy is larger at high frequencies.

Photons act as individual quanta and interact with individual electrons, atoms, molecules, and so on. The energy a photon carries is, thus, crucial to the effects it has. Table 29.3.1 lists representative submicroscopic energies in eV. When we compare photon energies from the EM spectrum in Figure 29.3.1 with energies in the table, we can see how effects vary with the type of EM radiation.

| Rotational energies of molecules | 10−5eV |

| Vibrational energies of molecules | 0.1 eV |

| Energy between outer electron shells in atoms | 1 eV |

| Binding energy of a weakly bound molecule | 1 eV |

| Energy of red light | 2 eV |

| Binding energy of a tightly bound molecule | 10 eV |

| Energy to ionize atom or molecule | 10 to 1000 eV |

Gamma rays, a form of nuclear and cosmic EM radiation, can have the highest frequencies and, hence, the highest photon energies in the EM spectrum. For example, a γ-ray photon with f=1021Hz has an energy E=hf=6.63×10−13J=4.14MeV. This is sufficient energy to ionize thousands of atoms and molecules, since only 10 to 1000 eV are needed per ionization. In fact, γ-rays are one type of ionizing radiation, as are x rays and UV, because they produce ionization in materials that absorb them. Because so much ionization can be produced, a single γ-ray photon can cause significant damage to biological tissue, killing cells or damaging their ability to properly reproduce. When cell reproduction is disrupted, the result can be cancer, one of the known effects of exposure to ionizing radiation. Since cancer cells are rapidly reproducing, they are exceptionally sensitive to the disruption produced by ionizing radiation. This means that ionizing radiation has positive uses in cancer treatment as well as risks in producing cancer.

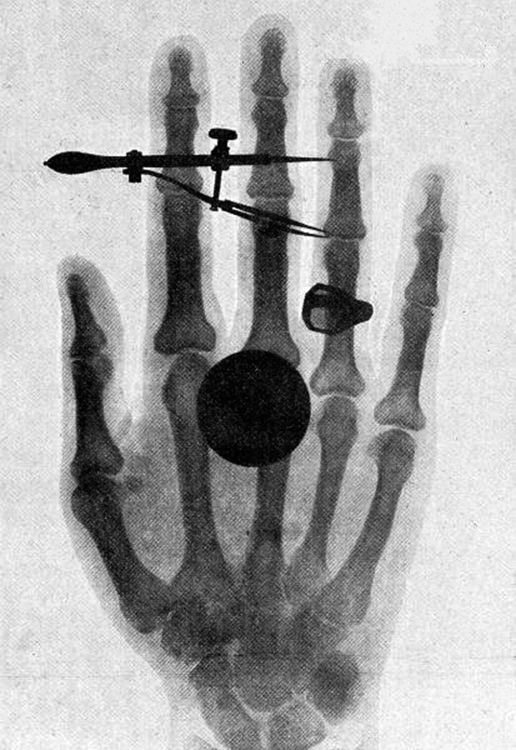

High photon energy also enables γ rays to penetrate materials, since a collision with a single atom or molecule is unlikely to absorb all the γ ray’s energy. This can make γ rays useful as a probe, and they are sometimes used in medical imaging. x rays, as you can see in Figure 29.3.1, overlap with the low-frequency end of the γ ray range. Since x rays have energies of keV and up, individual x-ray photons also can produce large amounts of ionization. At lower photon energies, x rays are not as penetrating as γ rays and are slightly less hazardous. X rays are ideal for medical imaging, their most common use, and a fact that was recognized immediately upon their discovery in 1895 by the German physicist W. C. Roentgen (1845–1923). (See Figure 29.3.2.) Within one year of their discovery, x rays (for a time called Roentgen rays) were used for medical diagnostics. Roentgen received the 1901 Nobel Prize for the discovery of x rays.

CONNECTIONS: CONSERVATION OF ENERGY

Once again, we find that conservation of energy allows us to consider the initial and final forms that energy takes, without having to make detailed calculations of the intermediate steps. Example 29.3.1 is solved by considering only the initial and final forms of energy.

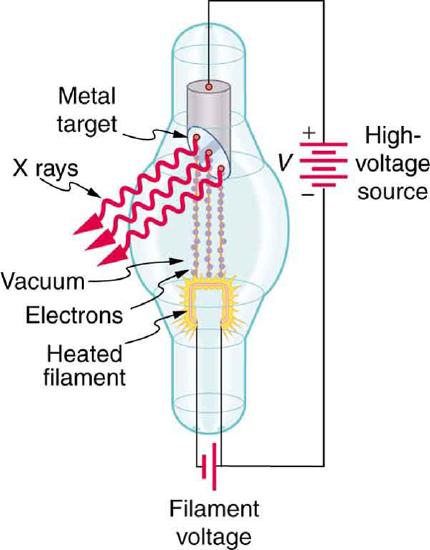

While γ rays originate in nuclear decay, x rays are produced by the process shown in Figure 29.3.3. Electrons ejected by thermal agitation from a hot filament in a vacuum tube are accelerated through a high voltage, gaining kinetic energy from the electrical potential energy. When they strike the anode, the electrons convert their kinetic energy to a variety of forms, including thermal energy. But since an accelerated charge radiates EM waves, and since the electrons act individually, photons are also produced. Some of these x-ray photons obtain the kinetic energy of the electron. The accelerated electrons originate at the cathode, so such a tube is called a cathode ray tube (CRT), and various versions of them are found in older TV and computer screens as well as in x-ray machines.

Example 29.3.1: X-ray Photon Energy and X-ray Tube Voltage

Find the maximum energy in eV of an x-ray photon produced by electrons accelerated through a potential difference of 50.0 kV in a CRT like the one in Figure 29.3.3.

Strategy

Electrons can give all of their kinetic energy to a single photon when they strike the anode of a CRT. (This is something like the photoelectric effect in reverse.) The kinetic energy of the electron comes from electrical potential energy. Thus we can simply equate the maximum photon energy to the electrical potential energy—that is, hf=qV. (We do not have to calculate each step from beginning to end if we know that all of the starting energy qV is converted to the final form hf.)

Solution

The maximum photon energy is hf=qV, where q is the charge of the electron and V is the accelerating voltage. Thus,

hf=(1.60×10−19C)(50.0×103V).

From the definition of the electron volt, we know 1eV=1.60×10−19J, where 1J=1C⋅V. Gathering factors and converting energy to eV yields

hf=(50.0×103)(1.60×10−19C⋅V)(1eV1.60×10−19C⋅V)

Discussion

This example produces a result that can be applied to many similar situations. If you accelerate a single elementary charge, like that of an electron, through a potential given in volts, then its energy in eV has the same numerical value. Thus a 50.0-kV potential generates 50.0 keV electrons, which in turn can produce photons with a maximum energy of 50 keV. Similarly, a 100-kV potential in an x-ray tube can generate up to 100-keV x-ray photons. Many x-ray tubes have adjustable voltages so that various energy x rays with differing energies, and therefore differing abilities to penetrate, can be generated.

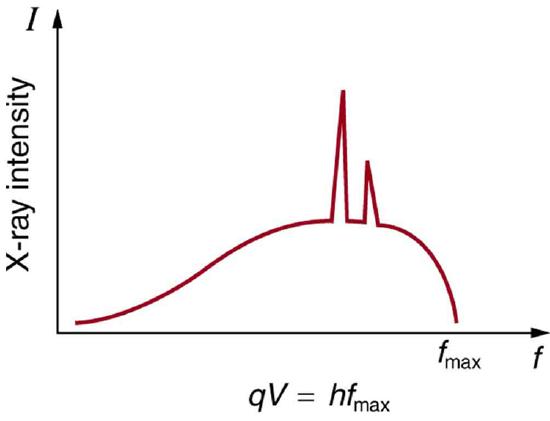

Figure 29.3.4 shows the spectrum of x rays obtained from an x-ray tube. There are two distinct features to the spectrum. First, the smooth distribution results from electrons being decelerated in the anode material. A curve like this is obtained by detecting many photons, and it is apparent that the maximum energy is unlikely. This decelerating process produces radiation that is called bremsstrahlung (German for braking radiation). The second feature is the existence of sharp peaks in the spectrum; these are called characteristic x rays, since they are characteristic of the anode material. Characteristic x rays come from atomic excitations unique to a given type of anode material. They are akin to lines in atomic spectra, implying the energy levels of atoms are quantized. Phenomena such as discrete atomic spectra and characteristic x rays are explored further in Atomic Physics.

Ultraviolet radiation (approximately 4 eV to 300 eV) overlaps with the low end of the energy range of x rays, but UV is typically lower in energy. UV comes from the de-excitation of atoms that may be part of a hot solid or gas. These atoms can be given energy that they later release as UV by numerous processes, including electric discharge, nuclear explosion, thermal agitation, and exposure to x rays. A UV photon has sufficient energy to ionize atoms and molecules, which makes its effects different from those of visible light. UV thus has some of the same biological effects as rays and x rays. For example, it can cause skin cancer and is used as a sterilizer. The major difference is that several UV photons are required to disrupt cell reproduction or kill a bacterium, whereas single γ-ray and X-ray photons can do the same damage. But since UV does have the energy to alter molecules, it can do what visible light cannot. One of the beneficial aspects of UV is that it triggers the production of vitamin D in the skin, whereas visible light has insufficient energy per photon to alter the molecules that trigger this production. Infantile jaundice is treated by exposing the baby to UV (with eye protection), called phototherapy, the beneficial effects of which are thought to be related to its ability to help prevent the buildup of potentially toxic bilirubin in the blood.

Example 29.3.2: Photon Energy and Effects for UV

Short-wavelength UV is sometimes called vacuum UV, because it is strongly absorbed by air and must be studied in a vacuum. Calculate the photon energy in eV for 100-nm vacuum UV, and estimate the number of molecules it could ionize or break apart.

Strategy

Using the equation E=hf

and appropriate constants, we can find the photon energy and compare it with energy information in Table.

Solution

The energy of a photon is given by

E=hf=hcλ.

Using hc=1240eV⋅nm, we find that

E=hcλ=1240eV⋅nm100nm=12.4eV.

Discussion

According to Table 29.3.1, this photon energy might be able to ionize an atom or molecule, and it is about what is needed to break up a tightly bound molecule, since they are bound by approximately 10 eV. This photon energy could destroy about a dozen weakly bound molecules. Because of its high photon energy, UV disrupts atoms and molecules it interacts with. One good consequence is that all but the longest-wavelength UV is strongly absorbed and is easily blocked by sunglasses. In fact, most of the Sun’s UV is absorbed by a thin layer of ozone in the upper atmosphere, protecting sensitive organisms on Earth. Damage to our ozone layer by the addition of such chemicals as CFC’s has reduced this protection for us.

Visible Light

The range of photon energies for visible light from red to violet is 1.63 to 3.26 eV, respectively (left for this chapter’s Problems and Exercises to verify). These energies are on the order of those between outer electron shells in atoms and molecules. This means that these photons can be absorbed by atoms and molecules. A single photon can actually stimulate the retina, for example, by altering a receptor molecule that then triggers a nerve impulse. Photons can be absorbed or emitted only by atoms and molecules that have precisely the correct quantized energy step to do so. For example, if a red photon of frequency f encounters a molecule that has an energy step, ΔE, equal to hf, then the photon can be absorbed. Violet flowers absorb red and reflect violet; this implies there is no energy step between levels in the receptor molecule equal to the violet photon’s energy, but there is an energy step for the red.

There are some noticeable differences in the characteristics of light between the two ends of the visible spectrum that are due to photon energies. Red light has insufficient photon energy to expose most black-and-white film, and it is thus used to illuminate darkrooms where such film is developed. Since violet light has a higher photon energy, dyes that absorb violet tend to fade more quickly than those that do not. (See Figure 29.3.5.) Take a look at some faded color posters in a storefront some time, and you will notice that the blues and violets are the last to fade. This is because other dyes, such as red and green dyes, absorb blue and violet photons, the higher energies of which break up their weakly bound molecules. (Complex molecules such as those in dyes and DNA tend to be weakly bound.) Blue and violet dyes reflect those colors and, therefore, do not absorb these more energetic photons, thus suffering less molecular damage.

Transparent materials, such as some glasses, do not absorb any visible light, because there is no energy step in the atoms or molecules that could absorb the light. Since individual photons interact with individual atoms, it is nearly impossible to have two photons absorbed simultaneously to reach a large energy step. Because of its lower photon energy, visible light can sometimes pass through many kilometers of a substance, while higher frequencies like UV, x ray, and γ rays are absorbed, because they have sufficient photon energy to ionize the material.

Example 29.3.3: How Many Photons per Second Does a Typical Light Bulb Produce?

Assuming that 10.0% of a 100-W light bulb’s energy output is in the visible range (typical for incandescent bulbs) with an average wavelength of 580 nm, calculate the number of visible photons emitted per second.

Strategy

Power is energy per unit time, and so if we can find the energy per photon, we can determine the number of photons per second. This will best be done in joules, since power is given in watts, which are joules per second.

Solution

The power in visible light production is 10.0% of 100 W, or 10.0 J/s. The energy of the average visible photon is found by substituting the given average wavelength into the formula

E=hcλ.

This produces

E=(6.63×10−34J⋅s)(3.00×108m/s580×10−9=3.43×10−19J.

The number of visible photons per second is thus

photon/s=10.0J/s3.43×10−19J/photon=2.92×1019photon/s

Discussion

This incredible number of photons per second is verification that individual photons are insignificant in ordinary human experience. It is also a verification of the correspondence principle—on the macroscopic scale, quantization becomes essentially continuous or classical. Finally, there are so many photons emitted by a 100-W lightbulb that it can be seen by the unaided eye many kilometers away.

Lower-Energy Photons

Infrared radiation (IR) has even lower photon energies than visible light and cannot significantly alter atoms and molecules. IR can be absorbed and emitted by atoms and molecules, particularly between closely spaced states. IR is extremely strongly absorbed by water, for example, because water molecules have many states separated by energies on the order of 10−5eV to 10−2eV well within the IR and microwave energy ranges. This is why in the IR range, skin is almost jet black, with an emissivity near 1—there are many states in water molecules in the skin that can absorb a large range of IR photon energies. Not all molecules have this property. Air, for example, is nearly transparent to many IR frequencies.

Microwaves are the highest frequencies that can be produced by electronic circuits, although they are also produced naturally. Thus microwaves are similar to IR but do not extend to as high frequencies. There are states in water and other molecules that have the same frequency and energy as microwaves, typically about 10−5eV. This is one reason why food absorbs microwaves more strongly than many other materials, making microwave ovens an efficient way of putting energy directly into food.

Photon energies for both IR and microwaves are so low that huge numbers of photons are involved in any significant energy transfer by IR or microwaves (such as warming yourself with a heat lamp or cooking pizza in the microwave). Visible light, IR, microwaves, and all lower frequencies cannot produce ionization with single photons and do not ordinarily have the hazards of higher frequencies. When visible, IR, or microwave radiation is hazardous, such as the inducement of cataracts by microwaves, the hazard is due to huge numbers of photons acting together (not to an accumulation of photons, such as sterilization by weak UV). The negative effects of visible, IR, or microwave radiation can be thermal effects, which could be produced by any heat source. But one difference is that at very high intensity, strong electric and magnetic fields can be produced by photons acting together. Such electromagnetic fields (EMF) can actually ionize materials.

MISCONCEPTION ALERT: HIGH VOLTAGE POWER LINES

- Although some people think that living near high-voltage power lines is hazardous to one’s health, ongoing studies of the transient field effects produced by these lines show their strengths to be insufficient to cause damage. Demographic studies also fail to show significant correlation of ill effects with high-voltage power lines. The American Physical Society issued a report over 10 years ago on power-line fields, which concluded that the scientific literature and reviews of panels show no consistent, significant link between cancer and power-line fields. They also felt that the “diversion of resources to eliminate a threat which has no persuasive scientific basis is disturbing.”

It is virtually impossible to detect individual photons having frequencies below microwave frequencies, because of their low photon energy. But the photons are there. A continuous EM wave can be modeled as photons. At low frequencies, EM waves are generally treated as time- and position-varying electric and magnetic fields with no discernible quantization. This is another example of the correspondence principle in situations involving huge numbers of photons.

PHET EXPLORATIONS: COLOR VISION

Make a whole rainbow by mixing red, green, and blue light. Change the wavelength of a monochromatic beam or filter white light. View the light as a solid beam, or see the individual photons.

Summary

- Photon energy is responsible for many characteristics of EM radiation, being particularly noticeable at high frequencies.

- Photons have both wave and particle characteristics.

Glossary

- gamma ray

- also γ-ray; highest-energy photon in the EM spectrum

- ionizing radiation

- radiation that ionizes materials that absorb it

- x ray

- EM photon between γ-ray and UV in energy

- bremsstrahlung

- German for braking radiation; produced when electrons are decelerated

- characteristic x rays

- x rays whose energy depends on the material they were produced in

- ultraviolet radiation

- UV; ionizing photons slightly more energetic than violet light

- visible light

- the range of photon energies the human eye can detect

- infrared radiation

- photons with energies slightly less than red light

- microwaves

- photons with wavelengths on the order of a micron (μm)0)