3.4: Nuclear mass formula

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

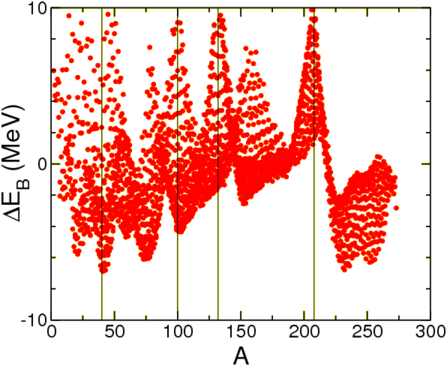

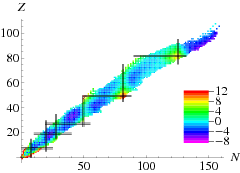

There is more structure in Figure 4.3.1 than just a simple linear dependence on A. A naive analysis suggests that the following terms should play a role:

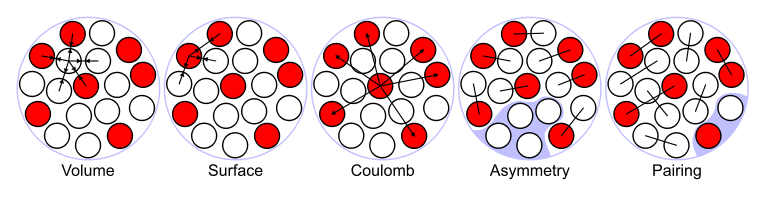

- Bulk energy: This is the term studied above, and saturation implies that the energy is proportional to Bbulk=αA.

- Surface energy: Nucleons at the surface of the nuclear sphere have less neighbors, and should feel less attraction. Since the surface area goes with R2, we find Bsurface=−βA.

- Pauli or symmetry energy: nucleons are fermions (will be discussed later). That means that they cannot occupy the same states, thus reducing the binding. This is found to be proportional to Bsymm=−γ(N/2−Z/2)2/A2.

- Coulomb energy: protons are charges and they repel. The average distance between is related to the radius of the nucleus, the number of interaction is roughly Z2 (or Z(Z−1)). We have to include the term BCoul=−ϵZ2/A.

Taking all this together we fit the formula

B(A,Z)=αA−βA2/3−γ(A/2−Z)2A−1−ϵZ2A−1/3

to all know nuclear binding energies with A≥16 (the formula is not so good for light nuclei). The fit results are given in Table 3.4.1.

| parameter | value |

|---|---|

| α | 15.36 MeV |

| β | 16.32 MeV |

| γ | 90.45 MeV |

| ϵ | 0.6928 MeV |

In Table 3.4.1 we show how well this fit works. There remains a certain amount of structure, see below, as well as a strong difference between neighbouring nuclei. This is due to the superfluid nature of nuclear material: nucleons of opposite momenta tend to anti-align their spins, thus gaining energy. The solution is to add a pairing term to the binding energy,

Bpair={A−1/2for N odd, Z odd−A−1/2for N even, Z even

The results including this term are significantly better, even though all other parameters remain at the same position (Table 3.4.2). Taking all this together we fit the formula

B(A,Z)=αA−βA2/3−γ(A/2−Z)2A−1−δBpair(A,Z)−ϵZ2A−1/3

| parameter | value |

|---|---|

| α | 15.36 MeV |

| β | 16.32 MeV |

| γ | 90.46 MeV |

| δ | 11.32 MeV |

| ϵ | 0.6929 MeV |