4.4: Systems with internal structure

- Page ID

- 3441

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- To determine whether Einstein’s original proof of \(E = mc^2\) has logical flaws

- Also determine whether the claimed result is only valid under certain conditions

Section 4.2 presented essentially Einstein’s original proof of \(E = mc^2\), which has been criticized on several grounds. A detailed discussion is given by Ohanian.1 Putting aside questions that are purely historical or concerned only with academic priority, we would like to know whether the proof has logical flaws, and also whether the claimed result is only valid under certain conditions. We need to consider the following questions:

- Does it matter whether the system being described has finite spatial extent, or whether the system is isolated?

- Does it matter whether parts of the system are moving at relativistic velocities?

- Does the low-velocity approximation used in Einstein’s proof make a difference?

- How do we handle a system that is not made out of point-like particles, e.g., a capacitor, in which some of the energy-momentum is in an electric field?

The following example demonstrates issues 1-3 and their logical connections; the definitional question 4 is addressed in chapter 9.

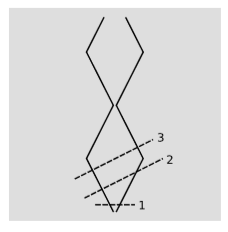

Suppose that two beads slide freely on a wire, bouncing elastically off of each other and also rebounding elastically from the wire’s ends. Their world-lines are shown in figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). Let’s say the beads each have unit mass. In frame \(o\), the beads are released from the center of the wire with velocities \(±u\). For concreteness, let’s set \(u = 1/2\), so that the system has internal motion at relativistic speeds. In this frame, the total energy-momentum vector of the system, on the surface of simultaneity labeled \(1\) in figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), is \(p = (2.31,0)\). That is, it has a total mass-energy of \(2.31\) units, and a total momentum of zero (meaning that this is the center of mass frame). As time goes on, an observer in this frame will say that the balls reach the ends of the wire simultaneously, at which point they rebound, maintaining the same total energy-momentum vector \(p\). The mass of the system is, by definition,

\[m = \sqrt{p_{t}^{2} - p_{x}^{2}} = \sqrt{2.31}\]

and this mass remains constant as the balls bounce back and forth. Now let’s transform into a frame \(o'\), moving at a velocity \(v = 1/2\) relative to \(o\). If velocities added linearly in relativity, then the initial velocities of the beads in this frame would be \(0\) and \(-1\), but of course a material object can’t move with speed \(|v| = c = 1\), and velocities don’t add linearly. Applying the correct velocity addition formula for relativity, we find that the beads have initial velocities \(0\) and \(-0.8\) in this frame, and if we compute their total energy-momentum vector, on surface of simultaneity \(2\) in figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), we get \(p' = (2.67,-1.33)\). This is exactly what we would have gotten by taking the original vector \(p\) and pushing it through a Lorentz transformation. That is, the energy-momentum vector seems to be acting like a good four-vector, even though the system has finite spatial extent and contains parts that move at relativistic speeds. In particular, this implies that the system has the same mass \(m = \sqrt{2.31}\) as in \(o\), since \(m\) is the norm of the \(p\) vector, and the norm of a vector stays the same under a Lorentz transformation.

But now consider surface \(3\), which, like \(2\), observer \(o'\) considers to be a surface of simultaneity. At this time, \(o'\) says that both beads are moving to the left. Between time \(2\) and time \(3\), \(o'\) says that the system’s total momentum has changed, while its total massenergy stayed constant. Its mass is different, and the total energy-momentum vector \(p'\) at time \(3\) is not related by a Lorentz transformation to the value of \(p\) at any time in frame \(o\). The reason for this misbehavior is that the right-hand bead has bounced off of the right end of the wire, but because \(o\) and \(o'\) have different opinions about simultaneity, \(o'\) says that there has not yet been any matching collision for the bead on the left.

But all of these difficulties arise only because we have left something out. When the right-hand bead bounces off of the right-hand end of the wire, this is a collision between the bead and the wire. After the collision, the wire rebounds to the right (or a vibration is created in it). By ignoring the rebound of the wire, we have violated the law of conservation of momentum. If we take into account the momentum imparted to the wire, then the energy-momentum vector of the whole system is conserved, and must therefore be the same at \(2\) and \(3\).

The upshot of all this is that \(E = mc^2\) and the four-vector nature of \(p\) are both valid for systems with finite spatial extent, provided that the systems are isolated. “Isolated” means simply that we should not gratuitously ignore anything such as the wire in this example that exchanges energy-momentum with our system. To give a general proof of this, it will be helpful to develop the idea of the stress-energy tensor (section 9.2), which allows a succinct statement of what we mean by conservation of energy-momentum. A proof is given in section 9.3.