11.3: Particle Conservation Laws

- Page ID

- 4556

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish three conservation laws: baryon number, lepton number, and strangeness

- Use rules to determine the total baryon number, lepton number, and strangeness of particles before and after a reaction

- Use baryon number, lepton number, and strangeness conservation to determine if particle reactions or decays occur

Conservation laws are critical to an understanding of particle physics. Strong evidence exists that energy, momentum, and angular momentum are all conserved in all particle interactions. The annihilation of an electron and positron at rest, for example, cannot produce just one photon because this violates the conservation of linear momentum. The special theory of relativity modifies definitions of momentum, energy, and other familiar quantities. In particular, the relativistic momentum of a particle differs from its classical momentum by a factor \(\gamma = 1/\sqrt{1 - (v/c)^2}\) that varies from 1 to \(\infty\), depending on the speed of the particle.

In previous chapters, we encountered other conservation laws as well. For example, charge is conserved in all electrostatic phenomena. Charge lost in one place is gained in another because charge is carried by particles. No known physical processes violate charge conservation. In the next section, we describe three less-familiar conservation laws: baryon number, lepton number, and strangeness. These are by no means the only conservation laws in particle physics.

Baryon Number Conservation

No conservation law considered thus far prevents a neutron from decaying via a reaction such as

\[n \rightarrow e^+ + e^-. \nonumber \]

This process conserves charge, energy, and momentum. However, it does not occur because it violates the law of baryon number conservation. This law requires that the total baryon number of a reaction is the same before and after the reaction occurs. To determine the total baryon number, every elementary particle is assigned a baryon number B. The baryon number has the value \(B = +1\) for baryons, –1 for antibaryons, and 0 for all other particles. Returning to the above case (the decay of the neutron into an electron-positron pair), the neutron has a value \(B = +1\), whereas the electron and the positron each has a value of 0. Thus, the decay does not occur because the total baryon number changes from 1 to 0. However, the proton-antiproton collision process

\[p + \overline{p} \rightarrow p + p \overline{p} + \overline{p}, \nonumber \]

does satisfy the law of conservation of baryon number because the baryon number is zero before and after the interaction. The baryon number for several common particles is given in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\).

| Particle name | Symbol | Lepton number \((L_e)\) | Lepton number \((L_{\mu})\) | Lepton number \((L_{\tau})\) | Baryon number (B) | Strange-ness number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron | \(e^-\) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Electron neutrino | \(\nu_e\) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Muon | \(\mu^-\) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Muon neutrino | \(\nu_{\mu}\) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tau | \(\tau^-\) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Tau neutrino | \(\nu_{\tau}\) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pion | \(\pi^+\) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Positive kaon | \(K^+\) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Negative kaon | \(K^-\) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | –1 |

| Proton | p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Neutron | n | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Lambda zero | \(\Lambda^0\) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | –1 |

| Positive sigma | \(\sum^+\) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | –1 |

| Negative sigma | \(\sum^-\) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | –1 |

| Xi zero | \(\Xi^0\) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | –2 |

| Negative xi | \(\Xi^-\) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | –2 |

| Omega | \(\Omega^-\) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | –3 |

Based on the law of conservation of baryon number, which of the following reactions can occur?

\[(a)\space \pi^- + p \rightarrow \pi^0 + n + \pi^- + \pi^+ \nonumber \]

\[(b)\space p + \overline{p} \rightarrow p + p + \overline{p} \nonumber \]

Strategy

Determine the total baryon number for the reactants and products, and require that this value does not change in the reaction.

Solution

For reaction (a), the net baryon number of the two reactants is \(0 + 1 = 1\) and the net baryon number of the four products is \(0 + 1 + 0 + 0 = 1\).

Since the net baryon numbers of the reactants and products are equal, this reaction is allowed on the basis of the baryon number conservation law.

For reaction (b), the net baryon number of the reactants is \(1 + (-1) = 0\) and the net baryon number of the proposed products is \(1 + 1 + (-1) = 1\). Since the net baryon numbers of the reactants and proposed products are not equal, this reaction cannot occur.

Significance

Baryon number is conserved in the first reaction, but not in the second. Baryon number conservation constrains what reactions can and cannot occur in nature.

What is the baryon number of a hydrogen nucleus?

- Answer

-

1

Lepton Number Conservation

Lepton number conservation states that the sum of lepton numbers before and after the interaction must be the same. There are three different lepton numbers: the electron-lepton number \(L_e\), the muon-lepton number \(L_{\mu}\), and the tau-lepton number \(L_{\tau}\). In any interaction, each of these quantities must be conserved separately. For electrons and electron neutrinos, \(L_e = 1\); for their antiparticles, \(L_e = -1\); all other particles have \(L_e = 0\). Similarly, \(L_{\mu} = 1\) for muons and muon neutrinos, \(L_{\mu} = -1\) for their antiparticles, and \(L_{\mu} = 0\) for all other particles. Finally, \(L_{\tau} = 1, \, -1\), or 0, depending on whether we have a tau or tau neutrino, their antiparticles, or any other particle, respectively. Lepton number conservation guarantees that the number of electrons and positrons in the universe stays relatively constant. (Note: The total lepton number is, as far as we know, conserved in nature. However, observations have shown variations of family lepton number (for example, \(L_e\)) in a phenomenon called neutrino oscillations.)

To illustrate the lepton number conservation law, consider the following known two-step decay process:

\[\pi^+ \rightarrow \mu^+ + \nu_{\mu} \nonumber \]

\[\mu^+ \rightarrow e^+ + \nu_e + \overline{\nu}_{\mu}. \nonumber \]

In the first decay, all of the lepton numbers for \(\pi^+\) are 0. For the products of this decay, \(L_{\mu} = -1\) for \(\mu^+\) and \(L_{\mu} = 1\) for \(\nu_{\mu}\). Therefore, muon-lepton number is conserved. Neither electrons nor tau are involved in this decay, so \(L_e = 0\) and \(L_{\tau} = 0\) for the initial particle and all decay products. Thus, electron-lepton and tau-lepton numbers are also conserved. In the second decay, \(\mu^+\) has a muon-lepton number \(L_{\mu} = -1\), whereas the net muon-lepton number of the decay products is \(0 + 0 + (-1) = -1\). Thus, the muon-lepton number is conserved. Electron-lepton number is also conserved, as \(L_e = 0\) for \(\mu^+\), whereas the net electron-lepton number of the decay products is \((-1) + 1 + 0 = 0\). Finally, since no taus or tau-neutrinos are involved in this decay, the tau-lepton number is also conserved.

Based on the law of conservation of lepton number, which of the following decays can occur?

\[(a) \, n \rightarrow p + e^- + \overline{\nu}_e \nonumber \]

\[(b) \, \pi^- \rightarrow \mu^- + \nu_{\mu} + \overline{\nu}_{\mu} \nonumber \]

Strategy

Determine the total lepton number for the reactants and products, and require that this value does not change in the reaction.

Solution

For decay (a), the electron-lepton number of the neutron is 0, and the net electron-lepton number of the decay products is \(0 + 1 + (-1) = 0\).

Since the net electron-lepton numbers before and after the decay are the same, the decay is possible on the basis of the law of conservation of electron-lepton number. Also, since there are no muons or taus involved in this decay, the muon-lepton and tauon-lepton numbers are conserved.

For decay (b), the muon-lepton number of the \(\pi^-\) is 0, and the net muon-lepton number of the proposed decay products is \(1 + 1 + (-1) = 1\).

Thus, on the basis of the law of conservation of muon-lepton number, this decay cannot occur.

Significance

Lepton number is conserved in the first reaction, but not in the second. Lepton number conservation constrains what reactions can and cannot occur in nature.

What is the lepton number of an electron-positron pair?

- Answer

-

0

Strangeness Conservation

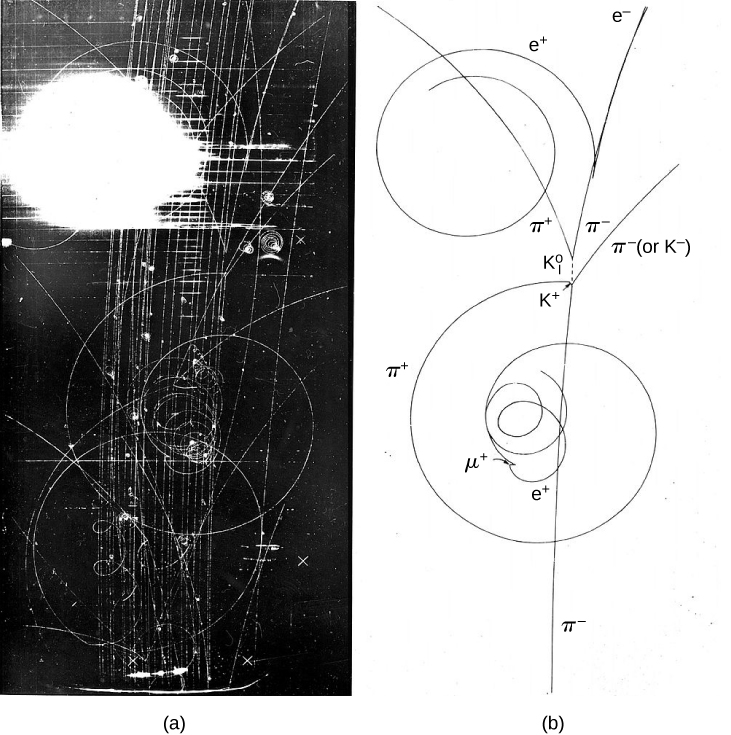

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, cosmic-ray experiments revealed the existence of particles that had never been observed on Earth. These particles were produced in collisions of pions with protons or neutrons in the atmosphere. Their production and decay were unusual. They were produced in the strong nuclear interactions of pions and nucleons, and were therefore inferred to be hadrons; however, their decay was mediated by the much more slowly acting weak nuclear interaction. Their lifetimes were on the order of \(10^{-10}\) to \(10^{-8} s\), whereas a typical lifetime for a particle that decays via the strong nuclear reaction is \(10^{-23}s\). These particles were also unusual because they were always produced in pairs in the pion-nucleon collisions. For these reasons, these newly discovered particles were described as strange. The production and subsequent decay of a pair of strange particles is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) and follows the reaction

\[\pi^- + p \rightarrow \Lambda^0 + K^0. \nonumber \]

The lambda particle then decays through the weak nuclear interaction according to

\[\Lambda^0 \rightarrow \pi^- + p, \nonumber \]

and the kaon decays via the weak interaction

\[K^0 \rightarrow \pi^+ + \pi^-. \nonumber \]

To rationalize the behavior of these strange particles, particle physicists invented a particle property conserved in strong interactions but not in weak interactions. This property is called strangeness and, as the name suggests, is associated with the presence of a strange quark. The strangeness of a particle is equal to the number of strange quarks of the particle. Strangeness conservation requires the total strangeness of a reaction or decay (summing the strangeness of all the particles) is the same before and after the interaction. Strangeness conservation is not absolute: It is conserved in strong interactions and electromagnetic interactions but not in weak interactions. The strangeness number for several common particles is given in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\).

(a) Based on the conservation of strangeness, can the following reaction occur?

\[\pi^- + p \rightarrow K^+ + K^- + n. \nonumber \]

(b) The following decay is mediated by the weak nuclear force:

\[K^+ \rightarrow \pi^+ + \pi^0. \nonumber \]

Does the decay conserve strangeness? If not, can the decay occur?

Strategy

Determine the strangeness of the reactants and products and require that this value does not change in the reaction.

Solution

- The net strangeness of the reactants is \(0 + 0 = 0\), and the net strangeness of the products is \(1 + (-1) + 0 = 0\).

- Thus, the strong nuclear interaction between a pion and a proton is not forbidden by the law of conservation of strangeness. Notice that baryon number is also conserved in the reaction.

- The net strangeness before and after this decay is 1 and 0, so the decay does not conserve strangeness. However, the decay may still be possible, because the law of conservation of strangeness does not apply to weak decays.

Significance

Strangeness is conserved in the first reaction, but not in the second. Strangeness conservation constrains what reactions can and cannot occur in nature.

What is the strangeness number of a muon?

- Answer

-

0