15.4: RLC Series Circuits with AC

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

By the end of the section, you will be able to:

- Describe how the current varies in a resistor, a capacitor, and an inductor while in series with an ac power source

- Use phasors to understand the phase angle of a resistor, capacitor, and inductor ac circuit and to understand what that phase angle means

- Calculate the impedance of a circuit

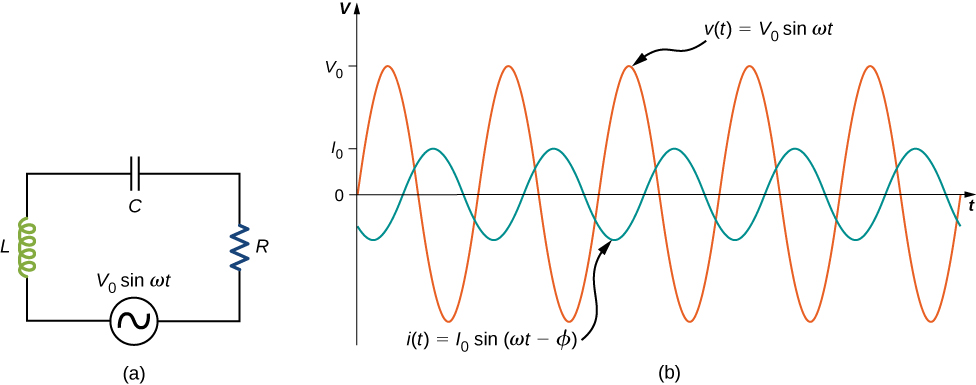

The ac circuit shown in Figure \PageIndex{1}, called an RLC series circuit, is a series combination of a resistor, capacitor, and inductor connected across an ac source. It produces an emf of

v(t) = V_0 \sin \omega t. \nonumber

Since the elements are in series, the same current flows through each element at all points in time. The relative phase between the current and the emf is not obvious when all three elements are present. Consequently, we represent the current by the general expression

i(t) = I_0 \, \sin (\omega t - \phi), \nonumber

where I_0 is the current amplitude and \phi is the phase angle between the current and the applied voltage. The phase angle is thus the amount by which the voltage and current are out of phase with each other in a circuit. Our task is to find I_0 and \phi.

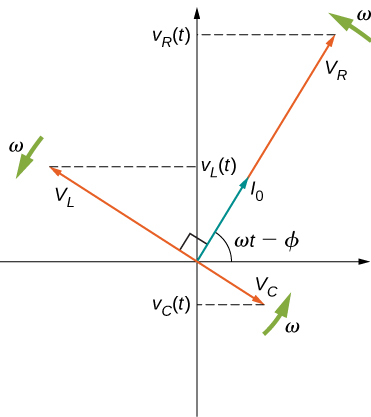

A phasor diagram involving i(t), v_R(t), v_C(t), and v_L(t) is helpful for analyzing the circuit. As shown in Figure \PageIndex{2}, the phasor representing v_R(t) points in the same direction as the phasor for i(t); its amplitude is V_R = I_0 R. The v_C(t) phasor lags the i(t) phasor by \pi/2 rad and has the amplitude V_C = I_0 X_C. The phasor for v_L(t) leads the i(t) phasor by \pi/2 rad and has the amplitude V_L = I_0 X_L.

At any instant, the voltage across the RLC combination is v_R(t) + v_L(t) + v_C(t) = v(t), the emf of the source. Since a component of a sum of vectors is the sum of the components of the individual vectors—for example, (A + B)_y = A_y + B_y - the projection of the vector sum of phasors onto the vertical axis is the sum of the vertical projections of the individual phasors. Hence, if we add vectorially the phasors representing v_R(t),\space v_L(t), and v_C(t) and then find the projection of the resultant onto the vertical axis, we obtain

v_R(t) + v_L(t) + v_C(t) = v(t) = V_0 \, sin \, \omega t. \nonumber

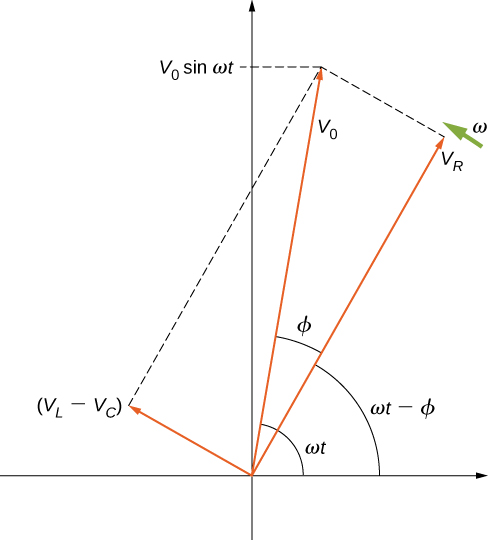

The vector sum of the phasors is shown in Figure \PageIndex{3}. The resultant phasor has an amplitudeV_0 and is directed at an angle \phi with respect to the v_R(t), or i(t), phasor. The projection of this resultant phasor onto the vertical axis is v(t) = V_0 \, sin \, \omega t. We can easily determine the unknown quantities I_0 and \phi from the geometry of the phasor diagram. For the phase angle,

\phi = tan^{-1} \frac{V_L - V_C}{V_R} = tan^{-1} \frac{I_0X_L - I_0X_C}{I_0R}, \nonumber

and after cancellation of I_0, this becomes

\phi = tan^{-1}\frac{X_L - X_C}{R}. \label{15.9}

Furthermore, from the Pythagorean theorem,

V_0 = \sqrt{V_R^2 + (V_L - V_C)^2} = \sqrt{(I_0R)^2 + (I_0X_L - I_) X_C)^2} = I_0 \sqrt{R^2 + (X_L - X_C)^2}. \nonumber

The current amplitude is therefore the ac version of Ohm’s law:

I_0 = \frac{V_0}{\sqrt{R^2 + (X_L - X_C)^2}} = \frac{V_0}{Z}, \label{eq1}

where

Z = \sqrt{R^2 + (X_L - X_C)^2} \label{eq2}

is known as the impedance of the circuit. Its unit is the ohm, and it is the ac analog to resistance in a dc circuit, which measures the combined effect of resistance, capacitive reactance, and inductive reactance (Figure \PageIndex{4}).

The RLC circuit is analogous to the wheel of a car driven over a corrugated road (Figure \PageIndex{5}). The regularly spaced bumps in the road drive the wheel up and down; in the same way, a voltage source increases and decreases. The shock absorber acts like the resistance of the RLC circuit, damping and limiting the amplitude of the oscillation. Energy within the wheel system goes back and forth between kinetic and potential energy stored in the car spring, analogous to the shift between a maximum current, with energy stored in an inductor, and no current, with energy stored in the electric field of a capacitor. The amplitude of the wheel’s motion is at a maximum if the bumps in the road are hit at the resonant frequency, which we describe in more detail in Resonance in an AC Circuit.

To analyze an ac circuit containing resistors, capacitors, and inductors, it is helpful to think of each device’s reactance and find the equivalent reactance using the rules we used for equivalent resistance in the past. Phasors are a great method to determine whether the emf of the circuit has positive or negative phase (namely, leads or lags other values). A mnemonic device of “ELI the ICE man” is sometimes used to remember that the emf (E) leads the current (I) in an inductor (L) and the current (I) leads the emf (E) in a capacitor (C).

Use the following steps to determine the emf of the circuit by phasors:

- Draw the phasors for voltage across each device: resistor, capacitor, and inductor, including the phase angle in the circuit.

- If there is both a capacitor and an inductor, find the net voltage from these two phasors, since they are antiparallel.

- Find the equivalent phasor from the phasor in step 2 and the resistor’s phasor using trigonometry or components of the phasors. The equivalent phasor found is the emf of the circuit.

The output of an ac generator connected to an RLC series combination has a frequency of 200 Hz and an amplitude of 0.100 V. If R = 4.00 \, \Omega, \, L = 3.00 \times 10^{-3} H, and C = 8.00 \times 10^{-4}F, what are (a) the capacitive reactance, (b) the inductive reactance, (c) the impedance, (d) the current amplitude, and (e) the phase difference between the current and the emf of the generator?

Strategy

The reactances and impedance in (a)–(c) are found by substitutions into Equation 15.3.8, Equation 15.3.14, and Equation \ref{eq1}, respectively. The current amplitude is calculated from the peak voltage and the impedance. The phase difference between the current and the emf is calculated by the inverse tangent of the difference between the reactances divided by the resistance.

Solution

- From Equation 15.3.8, the capacitive reactance is X_C = \frac{1}{\omega C} = \frac{1}{2\pi (200 \, Hz)(8.00 \times 10^{-4}F)} = 0.995 \, \Omega. \nonumber

- From Equation 15.3.14, the inductive reactance is X_L = \omega L = 2\pi(200 \, Hz)(3.00 \times 10^{-3}H) = 3.77 \, \Omega. \nonumber

- Substituting the values of R, X_C, and X_L into Equation \ref{eq1}, we obtain for the impedance Z = \sqrt{(4.00 \, )^2 + (3.77 \, \Omega - 0.995 \, \Omega)^2} = 4.87 \, \Omega. \nonumber

- The current amplitude is I_0 = \frac{V_0}{Z} = \frac{0.100 \, V}{4.87 \, \Omega} = 2.05 \times 10^{-2} A. \nonumber

- From Equation \ref{15.9}, the phase difference between the current and the emf is \phi = tan^{-1}\frac{X_L - X_C}{R} = tan^{-1}\frac{2.77 \, \Omega}{4.00 \, \Omega} = 0.607 \, rad. \nonumber

Significance

The phase angle is positive because the reactance of the inductor is larger than the reactance of the capacitor.

Find the voltages across the resistor, the capacitor, and the inductor in the circuit of Figure \PageIndex{1} using v(t) = V_0 \, sin \, \omega t as the output of the ac generator.

Solution

v_R = (V_0R/Z) \, sin \, (\omega t - \phi); v_C = (V_0X_C/Z) \, sin \, (\omega t - \phi + \pi2/) = - (V_0X_C/Z) \, cos \, (\omega t - \phi);

v_L = (V_0X_L/Z) \, sin \, (\omega t - \phi - \pi/2) = (V_0X_L/Z) \, cos \, (\omega t - \phi)