5.1: Free and Forced Oscillations

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

In Sec. 3.2 we briefly discussed oscillations in a keystone Hamiltonian system - a 1D harmonic oscillator described by a very simple Lagrangian 1 L≡T(˙q)−U(q)=m2˙q2−κ2q2,

Harmonic oscillator: equation m¨q+κq=0, i.e. ¨q+ω20q=0, with ω20≡κm≥0,

is a linear homogeneous differential equation. Its general solution is given by (3.16), which is frequently recast into another, amplitude-phase form: q(t)=ucosω0t+vsinω0t=Acos(ω0t−φ),

First of all, if the energy leaks out of the oscillator to its environment (the effect usually called the energy dissipation), the free oscillations decay with time. The simplest model of this effect is represented by an additional linear drag (or "kinematic friction") force, proportional to the generalized velocity and directed opposite to it: Fv=−η˙q,

In contrast to the decaying free oscillations, the forced oscillations, induced by an external force F(t), may maintain their amplitude (and hence energy) infinitely, even at non-zero damping. This process may be described using a still linear but now inhomogeneous differential equation m¨q+η˙q+κq=F(t),

Forced oscillator with damping ¨q+2δ˙q+ω20q=f(t), where f(t)≡F(t)/m.

For a mechanical linear, dissipative 1D oscillator (6), under the effect of an additional external force F(t), Eq. (13a) is just an expression of the 2nd Newton law. However, according to Eq. (1.41), Eq. (13) is valid for any dissipative, linear 6 1D system whose Gibbs potential energy (1.39) has the form UG(q,t)= κq2/2−F(t)q.

The forced-oscillation solutions may be analyzed by two mathematically equivalent methods whose relative convenience depends on the character of function f(t).

(i) Frequency domain. Representing the function f(t) as a Fourier sum of sinusoidal harmonics: 7 f(t)=∑ωfωe−iωt,

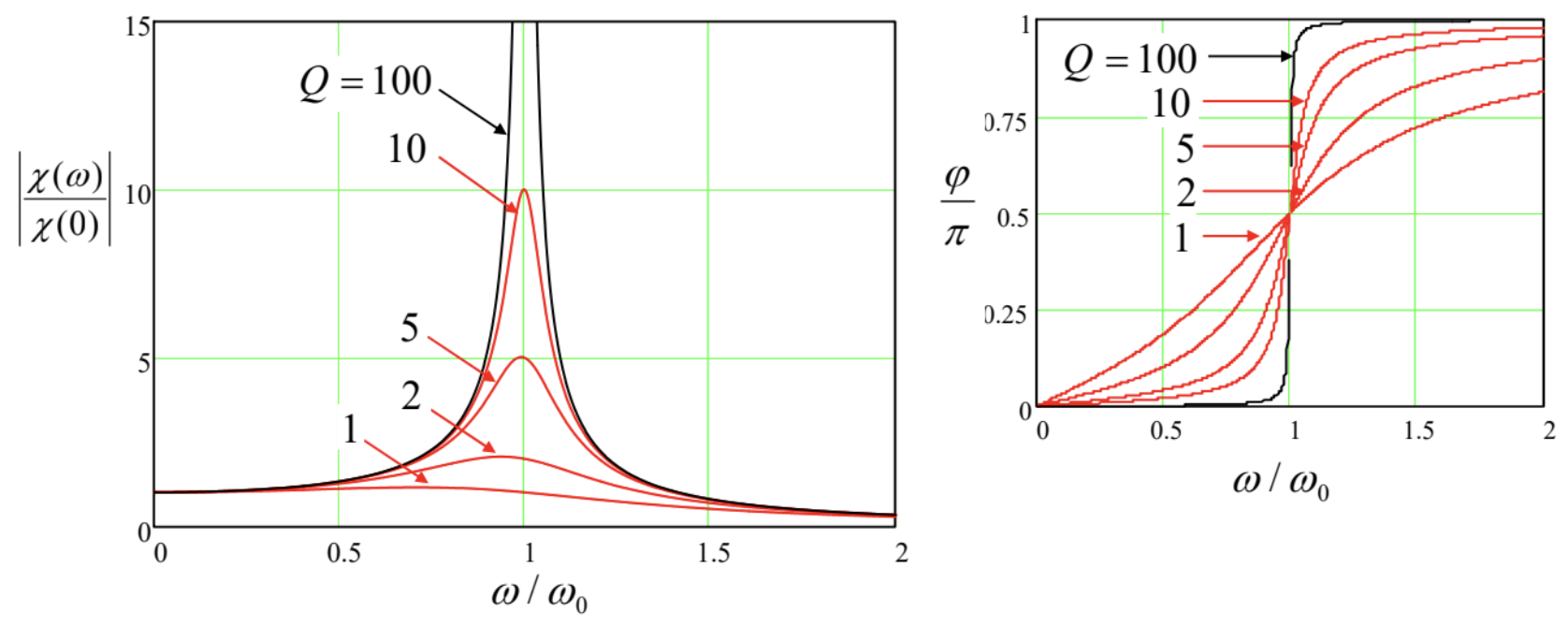

Figure 5.1. Resonance in the linear oscillator, for several values of Q.

Due to the increase of the resonance peak height, its width is inversely proportional to Q. Quantitatively, in the most interesting low-damping limit, i.e. at Q>>1, the reciprocal Q-factor gives the normalized value of the so-called full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the resonance curve: 9 Δωω0=1Q.

(ii) Time domain. Returning to arbitrary external force f(t), one may argue that Eqs. (9), (15)-(17) provide a full solution of the forced oscillation problem even in this general case. This is formally correct, but this solution may be very inconvenient if the external force is far from a sinusoidal function of time, especially if it is not periodic at all. In this case, we should first calculate the complex amplitudes fω participating in the Fourier sum (14). In the general case of a non-periodic f(t), this is actually the Fourier integral, 11 f(t)=∫+∞−∞fωe−iωtdt,

Fortunately, a straightforward calculation (left for the reader’s exercise) shows that the response function (17) satisfies the following rule: 12 ∫+∞−∞χ(ω)e−iωτdω=0, for τ<0.

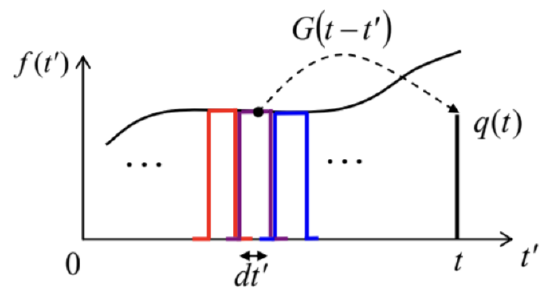

While the second form of Eq. (27) is frequently more convenient for calculations, its first form is more suitable for physical interpretation of the Green’s function. Indeed, let us consider the particular case when the force is a delta function f(t)=δ(t−t′), with t′<t, i.e. τ≡t−t′>0,

Figure 5.2. A schematic, finite-interval representation of a force f(t) as a sum of short pulses at all times t′<t, and their contributions to the linear system’s response q(t), as given by Eq. (27).

This picture may be used for the calculation of Green’s function for our particular system. Indeed, Eqs. (29)-(30) mean that G(τ) is just the solution of the differential equation of motion of the system, in our case, Eq. (13), with the replacement t→τ, and a δ-functional right-hand side: d2G(τ)dτ2+2δdG(τ)dτ+ω20G(τ)=δ(τ).

This calculation may be simplified even further. Let us integrate both sides of Eq. (31) over an infinitesimal interval including the origin, e.g. [- dτ/2,+dτ/2], and then follow the limit dτ→0. Since the Green’s function has to be continuous because of its physical sense as the (generalized) coordinate, all terms on the left-hand side but the first one vanish, while the first term yields dG/dτ|+0−dG/dτ|−0. Due to the second of Eqs. (32), the last of these two derivatives equals zero, while the right-hand side of Eq. (31) yields 1 upon the integration. Thus, the function G(τ) may be calculated for τ>0 (i.e. for all times when it is different from zero) by solving the homogeneous version of the system’s equation of motion for τ>0, with the following special initial conditions: G(0)=0,dGdτ(0)=1.

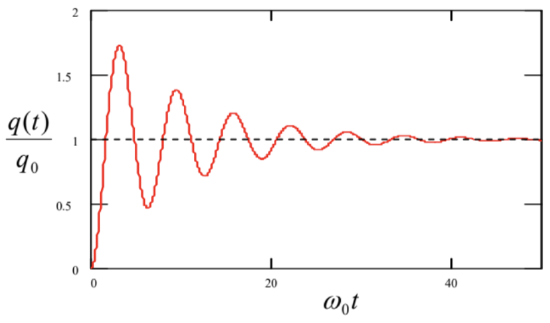

Relations (27) and (34) provide a very convenient recipe for solving many forced oscillations problems. As a very simple example, let us calculate the transient process in an oscillator under the effect of a constant force being turned on at t=0, i.e. proportional to the theta-function of time: f(t)=f0θ(t)≡{0, for t<0,f0, for t>0,

This result, plotted in Figure 3, is rather natural: it describes nothing more than the transient from the initial position q=0 to the new equilibrium position q0=f0/ω02=F0/κ, accompanied by decaying oscillations. For this particular simple function f(t), the same result might be also obtained by introducing a new variable ˜q(t)≡q(t)−q0 and solving the resulting homogeneous equation for ˜q (with appropriate initial condition ˜q(0)=−q0. However, for more complicated functions f(t) the Green’s function approach is irreplaceable.

Figure 5.3. The transient process in a linear oscillator, induced by a step-like force f(t), for the particular case δ/ω0=0.1 (i.e., Q=5 ).

Note that for any particular linear system, its Green’s function should be calculated only once, and then may be repeatedly used in Eq. (27) to calculate the system response to various external forces either analytically or numerically. This property makes the Green’s function approach very popular in many other fields of physics − with the corresponding generalization or re-definition of the function. 14

1 For the notation brevity, in this chapter I will drop indices "ef" in the energy components T and U, and parameters like m,κ, etc. However, the reader should still remember that T and U do not necessarily coincide with the actual kinetic and potential energies (even if those energies may be uniquely identified) - see Sec. 3.1.

2ω0 is usually called the own frequency of the oscillator. In quantum mechanics, the Germanized version of the same term, eigenfrequency, is used more. In this series, I will use either of the terms, depending on the context.

3 Note that this is the so-called physics convention. Most engineering texts use the opposite sign in the imaginary exponent, exp{−iωt}→exp{iωt}, with the corresponding sign implications for intermediate formulas, but (of course) similar final results for real variables.

4 Here Eq. (5) is treated as a phenomenological model, but in statistical mechanics, such dissipative term may be derived as an average force exerted upon a system by its environment, at very general assumptions. As discussed in detail elsewhere in this series (SM Chapter 5 and QM Chapter 7), due to the numerous degrees of freedom of a typical environment (think about the molecules of air surrounding the usual mechanical pendulum), its force also has a random component; as a result, the dissipation is fundamentally related to fluctuations. The latter effects may be neglected (as they are in this course) only if E is much higher than the energy scale of the random fluctuations of the oscillator - in the thermal equilibrium at temperature T, the larger of kBT and ℏω0/2.

5 Systems with high damping (δ>ω0) can hardly be called oscillators, and though they are used in engineering and physics experiment (e.g., for the shock, vibration, and sound isolation), for their detailed discussion I have to refer the interested reader to special literature - see, e.g., C. Harris and A. Piersol, Shock and Vibration Handbook, 5th ed., McGraw Hill, 2002. Let me only note that dynamics of systems with very high damping (δ≫> ω0 ) has two very different time scales: a relatively short "momentum relaxation time" 1/λ≈1/2δ=m/η, and a much longer "coordinate relaxation time" 1/λ+≈2δ/ω02=η/κ.

6 This is a very unfortunate, but common jargon, meaning "the system described by linear equations of motion".

7 Here, in contrast to Eq. (3b), we may drop the operator Re, assuming that f−ω=fω∗, so that the imaginary components of the sum compensate each other.

8 In physics, this mathematical property of linear equations is frequently called the linear superposition principle.

9 Note that the phase shift φ≡arg[χ(ω)] between the oscillations and the external force (see the right panel in Figure 1) makes its steepest change, by π/2, within the same frequency interval Δω.

10 Such function of frequency is met in many branches of science, frequently under special names, including the "Cauchy distribution", "the Lorentz function" (or "Lorentzian line", or "Lorentzian distribution"), "the BreitWigner function" (or "the Breit-Wigner distribution"), etc.

11 Let me hope that the reader knows that Eq. (23) may be used for periodic functions as well; in such a case, fω is a set of equidistant delta functions. (A reminder of the basic properties of the Dirac δ-function may be found, for example, in MA Sec. 14.)

12 Eq. (26) remains true for any linear physical systems in which f(t) represents a cause, and q(t) its effect. Following tradition, I discuss the frequency-domain expression of this causality relation (called the KramersKronig relations) in the Classical Electrodynamics part of this lecture series - see EM Sec. 7.2.

13 Technically, for this integration, t ’ in Eq. (27) should be temporarily replaced with another letter, say t ".

14 See, e.g., EM Sec. 2.7, and QM Sec. 2.2.