19.5: Atomic Spectra

- Page ID

- 32868

The best evidence for atomic energy levels comes from the emission of light by atoms in a gas at low pressure. If the atoms are put in an excited state by some mechanism, say, collisions with energetic electrons accelerated by a potential difference between electrodes, then light is emitted at particular frequencies called spectral lines. These frequencies can be separated by a device called a spectroscope. Spectroscopes use either a prism or a diffraction grating and ancillary optics to make the separation visible to the eye.

The frequency of a spectral line is equal to the energy difference between two states divided by Planck’s constant. This is a consequence of the conservation of energy — the energy released when an atom undergoes a transition from a state with energy \(\mathrm{E}_{2}\) to a state with energy \(\mathrm{E}_{1}\) is just the difference between these energies. The frequency of the emitted photon is then derived from the Planck formula. In terms of the angular frequency,

\[\omega_{21}=\frac{E_{2}-E_{1}}{\hbar}\label{19.16}\]

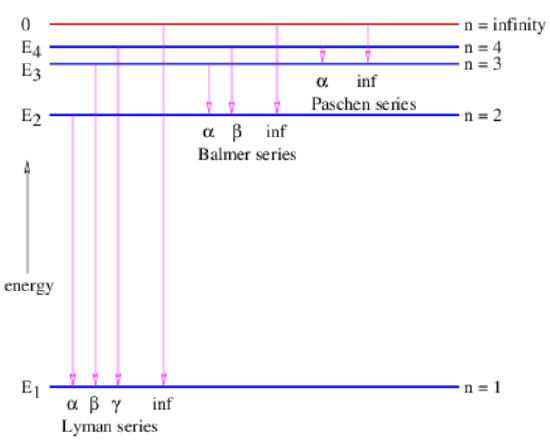

Figure 19.3 shows the possible transitions between the lowest four energy levels of hydrogen plus the ionized state in which the electron is initially a large distance from the hydrogen nucleus. Transitions from any state to the ground state form a series called the Lyman series, while transitions to the first excited state are called the Balmer series, transitions to the second excited state are called the Paschen series, and so on. Within each series, increasing frequencies are labeled using the Greek alphabet, so the transition from \(n = 2\) to \(n = 1\) is called the Lyman-α spectral line, etc.

Atoms can absorb as well as emit radiation. For instance, if hydrogen atoms in the ground state are bombarded with photons of energy equal to the energy difference between the ground state and some excited state, some of the atoms will absorb these photons and undergo transitions to the excited state. If white light (i. e., many photons with a continuous distribution of frequencies) irradiates such atoms, just those photons with the right energies will be absorbed. Examination of the light with a spectroscope after it passes through a gas of atoms will show absorption lines where the photons with the critical energies have been removed. This is one of the main ways in which astrophysicists learn about the elemental constitution of stars and interstellar gases.

Atoms in excited states emit photons spontaneously. However, a process called stimulated emission is also possible. This occurs when a photon with energy equal to the difference between two atomic energy levels interacts with an atom in the higher energy state. The amplitude for this process is equal to the spontaneous emission amplitude times \(n + 1\), where n is the number of incident photons with energy equal to the energy of the photon which would be spontaneously emitted. If a beam of photons with the right energy shines on atoms in an excited state, the beam will gain energy at a rate that is proportional to the initial intensity of the beam. For intense beams, this stimulated emission process overwhelms spontaneous emission and a large amount of energy can be rapidly extracted from the excited atoms. This is how a laser works.