14.5: RL Circuits

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Analyze circuits that have an inductor and resistor in series

- Describe how current and voltage exponentially grow or decay based on the initial conditions

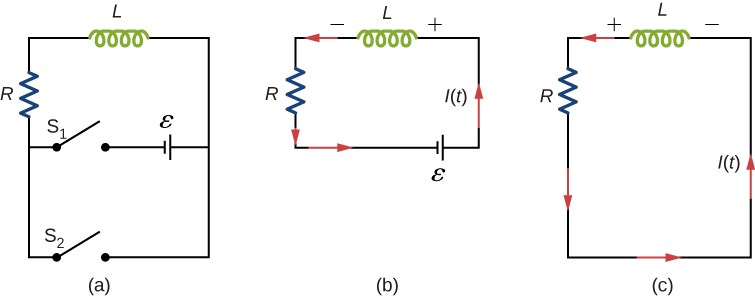

A circuit with resistance and self-inductance is known as an RL circuit. Figure 14.5.1a shows an RL circuit consisting of a resistor, an inductor, a constant source of emf, and switches S1 and S2. When S1 is closed, the circuit is equivalent to a single-loop circuit consisting of a resistor and an inductor connected across a source of emf (Figure 14.5.1b). When S1 is opened and S2 is closed, the circuit becomes a single-loop circuit with only a resistor and an inductor (Figure 14.5.1c).

We first consider the RL circuit of Figure 14.5.1b. Once S1 is closed and S2 is open, the source of emf produces a current in the circuit. If there were no self-inductance in the circuit, the current would rise immediately to a steady value of ϵ/R. However, from Faraday’s law, the increasing current produces an emf VL=−L(dI/dt) across the inductor. In accordance with Lenz’s law, the induced emf counteracts the increase in the current and is directed as shown in the figure. As a result, I(t) starts at zero and increases asymptotically to its final value.

Applying Kirchhoff’s loop rule to this circuit, we obtain

ϵ−LdIdt−IR=0,

which is a first-order differential equation for I(t). Notice its similarity to the equation for a capacitor and resistor in series (see RC Circuits). Similarly, the solution to Equation ??? can be found by making substitutions in the equations relating the capacitor to the inductor. This gives

I(t)=ϵR(1−e−Rt/L)=ϵR(1−e−t/τL),

where

τL=L/R

is the inductive time constant of the circuit.

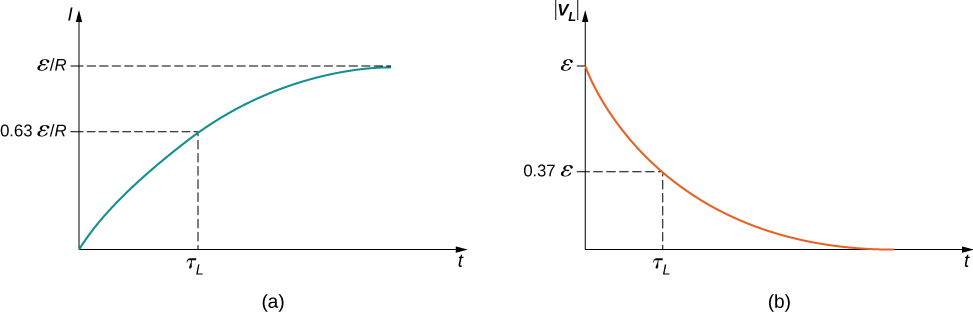

The current I(t) is plotted in Figure 14.5.2a. It starts at zero, and as t→∞, I(t) approaches ϵ/R asymptotically. The induced emf VL(t) is directly proportional to dI/dt, or the slope of the curve. Hence, while at its greatest immediately after the switches are thrown, the induced emf decreases to zero with time as the current approaches its final value of ϵ/R. The circuit then becomes equivalent to a resistor connected across a source of emf.

The energy stored in the magnetic field of an inductor is

UL=12LI2.

Thus, as the current approaches the maximum current ϵ/R, the stored energy in the inductor increases from zero and asymptotically approaches a maximum of L(ϵ/R)2/2.

The time constant τL tells us how rapidly the current increases to its final value. At t=τL, the current in the circuit is, from Equation 14.5.3,

I(τL)=ϵR(1−e−1)=0.63ϵR,

which is 63% of the final ϵ/R. The smaller the inductive time constant τL=L/R, the more rapidly the current approaches ϵ/R.

We can find the time dependence of the induced voltage across the inductor in this circuit by using VL(t)=−L(dI/dt) and Equation 14.5.3:

VL(t)=−LdIdt=−ϵe−t/τL.

The magnitude of this function is plotted in Figure 14.5.2b. The greatest value of L(dI/dt) is ϵ; it occurs when dI/dt is greatest, which is immediately after S1 is closed and S2 is opened. In the approach to steady state, dI/dt decreases to zero. As a result, the voltage across the inductor also vanishes as t→∞.

The time constant τL also tells us how quickly the induced voltage decays. At t=τL the magnitude of the induced voltage is

|VL(τL)|=ϵe−1=0.37ϵ=0.37V(0).

The voltage across the inductor therefore drops to about 37% of its initial value after one time constant. The shorter the time constant τL, the more rapidly the voltage decreases.

After enough time has elapsed so that the current has essentially reached its final value, the positions of the switches in Figure 14.5.1a are reversed, giving us the circuit in part (c). At t=0, the current in the circuit is I(0)=ϵ/R. With Kirchhoff’s loop rule, we obtain

IR+LdIdt=0.

The solution to this equation is similar to the solution of the equation for a discharging capacitor, with similar substitutions. The current at time t is then

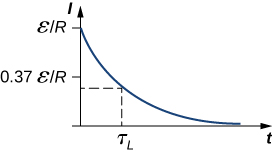

I(t)=ϵRe−t/τL.

The current starts at I(0)=ϵ/R and decreases with time as the energy stored in the inductor is depleted (Figure 14.5.3).

The time dependence of the voltage across the inductor can be determined from VL=−L(dI/dt):

VL(0)=ϵe−t/τL.

This voltage is initially VL(0)=ϵ, and it decays to zero like the current. The energy stored in the magnetic field of the inductor, LI2/2, also decreases exponentially with time, as it is dissipated by Joule heating in the resistance of the circuit.

In the circuit of Figure 14.5.1a, let ϵ=2.0V,R=4.0Ω, and L=4.0H. With S1 closed and S2 open (Figure 14.5.1b), (a) what is the time constant of the circuit? (b) What are the current in the circuit and the magnitude of the induced emf across the inductor at t=0, at t=2.0τL, and as t→∞?

Strategy

The time constant for an inductor and resistor in a series circuit is calculated using Equation ???. The current through and voltage across the inductor are calculated by the scenarios detailed from Equation 14.5.3 and Equation ???.

Solution

- The inductive time constant is τL=LR=4.0H4.0Ω=1.0s.

- The current in the circuit of Figure 14.5.1b increases according to Equation 14.5.3: I(t)=ϵR(1−e−t/τL). At t=0, (1−e−t/τL)=(1−1)=0;soI(0)=0. At t=2.0τL and t→∞, we have, respectively, I(2.0τL)=ϵR(1−e−2.0)=(0.50A)(0.86)=0.43A and I(∞)=ϵR=0.50A. From Equation ???, the magnitude of the induced emf decays as |VL(t)|=ϵe−t/τL. At t=0, t=2.0τL, and as t→∞, we obtain |VL(0)|=ϵ=V, |VL(2.0τL)|=(2.0V)e−2.0=0.27V and |VL(∞)|=0.

Significance

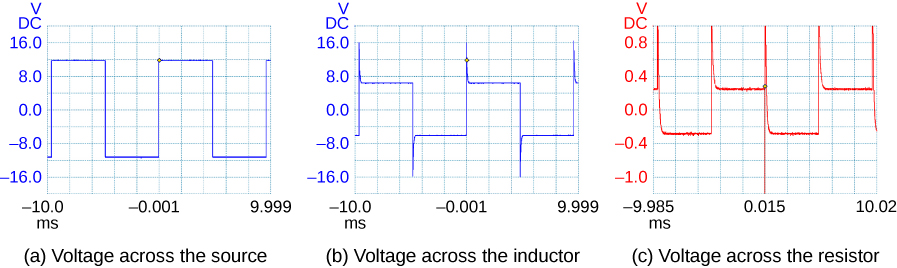

If the time of the measurement were much larger than the time constant, we would not see the decay or growth of the voltage across the inductor or resistor. The circuit would quickly reach the asymptotic values for both of these (Figure 14.5.4).

After the current in the RL circuit of Example 14.5.1 has reached its final value, the positions of the switches are reversed so that the circuit becomes the one shown in Figure 14.5.1c.

- How long does it take the current to drop to half its initial value?

- How long does it take before the energy stored in the inductor is reduced to 1.0% of its maximum value?

Strategy

The current in the inductor will now decrease as the resistor dissipates this energy. Therefore, the current falls as an exponential decay. We can also use that same relationship as a substitution for the energy in an inductor formula to find how the energy decreases at different time intervals.

Solution

- With the switches reversed, the current decreases according to I(t)=ϵRe−t/τL=I(0)e−t/τL. At a time t when the current is one-half its initial value, we have I(t)=0.50I(0) soe−t/τL=0.50, and t=−[ln(0.50)]τL=0.69(1.0s)=0.69s where we have used the inductive time constant found in Example 14.5.1.

- The energy stored in the inductor is given by UL(t)=12L[I(t)]2=12L(ϵRe−t/τL)2=Lϵ22R2e−2t/τL. If the energy drops to 1.0% of its initial value at a time t, we have UL(t)=(0.010)UL(0)orLϵ22R2e−2t/τL=(0.010)Lϵ22R2. Upon canceling terms and taking the natural logarithm of both sides, we obtain −2tτL=ln(0.010), so t=−12τLln(0.010). Since τL=1.0s, the time it takes for the energy stored in the inductor to decrease to 1.0% of its initial value is t=−12(1.0s)ln(0.010)=2.3s.

Significance

This calculation only works if the circuit is at maximum current in situation (b) prior to this new situation. Otherwise, we start with a lower initial current, which will decay by the same relationship.

Verify that RC and L/R have the dimensions of time

- If the current in the circuit of in Figure 14.5.1b increases to 90% of its final value after 5.0 s, what is the inductive time constant?

- If R=20Ω, what is the value of the self-inductance?

- If the R=20Ω resistor is replaced with a R=100Ω resistor, what is the time taken for the current to reach 90% of its final value?

- Answer

-

a. 2.2 s; b. 43 H; c. 1.0 s

For the circuit of in Figure 14.5.1b, show that when steady state is reached, the difference in the total energies produced by the battery and dissipated in the resistor is equal to the energy stored in the magnetic field of the coil