23.7: Small Oscillations

- Page ID

- 25896

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Any object moving subject to a force associated with a potential energy function that is quadratic will undergo simple harmonic motion,

\[U(x)=U_{0}+\frac{1}{2} k\left(x-x_{e q}\right)^{2} \nonumber \]

where k is a “spring constant”, \(x_{e q}\) is the equilibrium position, and the constant \(U_{0}\) just depends on the choice of reference point \(x_{r e f}\) for zero potential energy, \(U\left(x_{r e f}\right)=0\),

\[0=U\left(x_{r e f}\right)=U_{0}+\frac{1}{2} k\left(x_{r e f}-x_{e q}\right)^{2} \nonumber \]

Therefore the constant is

\[U_{0}=-\frac{1}{2} k\left(x_{r e f}-x_{e q}\right)^{2} \nonumber \]

The minimum of the potential \(x_{0}\) corresponds to the point where the x -component of the force is zero,

\[\left.\frac{d U}{d x}\right|_{x=x_{0}}=2 k\left(x_{0}-x_{e q}\right)=0 \Rightarrow x_{0}=x_{e q} \nonumber \]

corresponding to the equilibrium position. Therefore the constant is \(U\left(x_{0}\right)=U_{0}\) and we rewrite our potential function as

\[U(x)=U\left(x_{0}\right)+\frac{1}{2} k\left(x-x_{0}\right)^{2} \nonumber \]

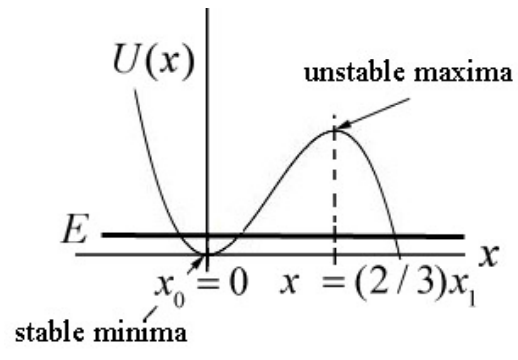

Now suppose that a potential energy function is not quadratic but still has a minimum at \(x_{0}\). For example, consider the potential energy function

\[U(x)=-U_{1}\left(\left(\frac{x}{x_{1}}\right)^{3}-\left(\frac{x}{x_{1}}\right)^{2}\right) \nonumber \]

(Figure 23.22), which has a stable minimum at \(x_{0}\),

When the energy of the system is very close to the value of the potential energy at the minimum \(U\left(x_{0}\right)\), we shall show that the system will undergo small oscillations about the minimum value \(x_{0}\). We shall use the Taylor formula to approximate the potential function as a polynomial. We shall show that near the minimum \(x_{0}\) we can approximate the potential function by a quadratic function similar to Equation (23.7.5) and show that the system undergoes simple harmonic motion for small oscillations about the minimum \(x_{0}\).

We begin by expanding the potential energy function about the minimum point using the Taylor formula

\[U(x)=U\left(x_{0}\right)+\left.\frac{d U}{d x}\right|_{x=x_{0}}\left(x-x_{0}\right)+\left.\frac{1}{2 !} \frac{d^{2} U}{d x^{2}}\right|_{x=x_{0}}\left(x-x_{0}\right)^{2}+\left.\frac{1}{3 !} \frac{d^{3} U}{d x^{3}}\right|_{x=x_{0}}\left(x-x_{0}\right)^{3}+\cdots \nonumber \]

where \(\left.\frac{1}{3 !} \frac{d^{3} U}{d x^{3}}\right|_{x=x_{0}}\left(x-x_{0}\right)^{3}\) is a third order term in that it is proportional to \(\left(x-x_{0}\right)^{3}\), and \(\left.\frac{d^{3} U}{d x^{3}}\right|_{x=x_{0}},\left.\frac{d^{2} U}{d x^{2}}\right|_{x=x_{0}}, \quad \text { and }\left.\frac{d U}{d x}\right|_{x=x_{0}}\) are constants. If \(x_{0}\) is the minimum of the potential energy, then the linear term is zero, because

\[\left.\frac{d U}{d x}\right|_{x=x_{0}}=0 \nonumber \]

and so Equation ((23.7.7)) becomes

\[U(x) \simeq U\left(x_{0}\right)+\left.\frac{1}{2} \frac{d^{2} U}{d x^{2}}\right|_{x=x_{0}}\left(x-x_{0}\right)^{2}+\left.\frac{1}{3 !} \frac{d^{3} U}{d x^{3}}\right|_{x=x_{0}}\left(x-x_{0}\right)^{3}+\cdots \nonumber \]

For small displacements from the equilibrium point such that \(\left|x-x_{0}\right|\) is sufficiently small, the third order term and higher order terms are very small and can be ignored. Then the potential energy function is approximately a quadratic function,

\[U(x) \simeq U\left(x_{0}\right)+\left.\frac{1}{2} \frac{d^{2} U}{d x^{2}}\right|_{x=x_{0}}\left(x-x_{0}\right)^{2}=U\left(x_{0}\right)+\frac{1}{2} k_{e f f}\left(x-x_{0}\right)^{2} \nonumber \]

where we define \(k_{eff}\), the effective spring constant, by

\[\left.k_{e f f} \equiv \frac{d^{2} U}{d x^{2}}\right|_{x=x_{0}} \nonumber \]

Because the potential energy function is now approximated by a quadratic function, the system will undergo simple harmonic motion for small displacements from the minimum with a force given by

\[F_{x}=-\frac{d U}{d x}=-k_{e f f}\left(x-x_{0}\right) \nonumber \]

At \(x=x_{0}\), the force is zero

\[F_{x}\left(x_{0}\right)=\frac{d U}{d x}\left(x_{0}\right)=0 \nonumber \]

We can determine the period of oscillation by substituting Equation (23.7.12) into Newton’s Second Law

\[-k_{eff}\left(x-x_{0}\right)=m_{eff} \frac{d^{2} x}{d t^{2}} \nonumber \]

where \(m_{eff}\) is the effective mass. For a two-particle system, the effective mass is the reduced mass of the system.

\[m_{eff}=\frac{m_{1} m_{2}}{m_{1}+m_{2}} \equiv \mu_{red} \nonumber \]

Equation (23.7.14) has the same form as the spring-object ideal oscillator. Therefore the angular frequency of small oscillations is given by

\[\omega_{0}=\sqrt{\frac{k_{e f f}}{m_{e f f}}}=\sqrt{(\left.\frac{d^{2} U}{d x^{2}}\right|_{x=x_{0}})/{m_{e f f}}} \nonumber \]

Example 23.6: Quartic Potential

A system with effective mass m has a potential energy given by

\[U(x)=U_{0}\left(-2\left(\frac{x}{x_{0}}\right)^{2}+\left(\frac{x}{x_{0}}\right)^{4}\right) \nonumber \]

where \(U_{0}\) and \(x_{0}\) are positive constants and \(U(0)=0\) (a) Find the points where the force on the particle is zero. Classify these points as stable or unstable. Calculate the value of \(U(x) / U_{0}\) at these equilibrium points. (b) If the particle is given a small displacement from an equilibrium point, find the angular frequency of small oscillation.

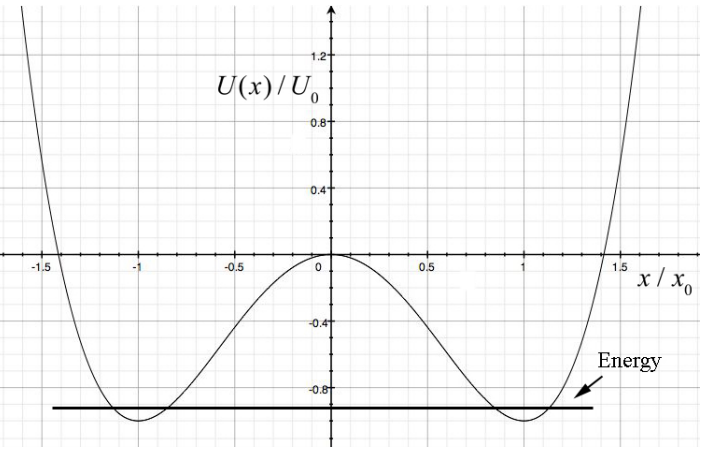

Solution: (a) A plot of \(U(x) / U_{0}\) as a function of \(x / x_{0}\) is shown in Figure 23.23.

The force on the particle is zero at the minimum of the potential energy,

\[\begin{array}{l}

0=\frac{d U}{d x}=U_{0}\left(-4\left(\frac{1}{x_{0}}\right)^{2} x+4\left(\frac{1}{x_{0}}\right)^{4} x^{3}\right) \\

=-4 U_{0} x\left(\frac{1}{x_{0}}\right)^{2}\left(1-\left(\frac{x}{x_{0}}\right)^{2}\right) \Rightarrow x^{2}=x_{0}^{2} \text { and } x=0

\end{array} \nonumber \]

The equilibrium points are at \(x=\pm x_{0}\) which are stable and x = 0 which is unstable. The second derivative of the potential energy is given by

\[\frac{d^{2} U}{d x^{2}}=U_{0}\left(-4\left(\frac{1}{x_{0}}\right)^{2}+12\left(\frac{1}{x_{0}}\right)^{4} x^{2}\right) \nonumber \]

If the particle is given a small displacement from \(x=x_{0}\) then

\[\left.\frac{d^{2} U}{d x^{2}}\right|_{x=x_{0}}=U_{0}\left(-4\left(\frac{1}{x_{0}}\right)^{2}+12\left(\frac{1}{x_{0}}\right)^{4} x_{0}^{2}\right)=U_{0} \frac{8}{x_{0}^{2}} \nonumber \]

(b) The angular frequency of small oscillations is given by

\[\omega_{0}=\sqrt{\left.\frac{d^{2} U}{d x^{2}}\right|_{x=x_{0}} / m}=\sqrt{\frac{8 U_{0}}{m x_{0}^{2}}} \nonumber \]

Example 23.7: Lennard-Jones 6-12 Potential

A commonly used potential energy function to describe the interaction between two atoms is the Lennard-Jones 6-12 potential

\[U(r)=U_{0}\left[\left(r_{0} / r\right)^{12}-2\left(r_{0} / r\right)^{6}\right] ; r>0 \nonumber \]

where r is the distance between the atoms. Find the angular frequency of small oscillations about the stable equilibrium position for two identical atoms bound to each other by the LennardJones interaction. Let m denote the effective mass of the system of two atoms.

Solution: The equilibrium points are found by setting the first derivative of the potential energy equal to zero,

\[0=\frac{d U}{d r}=U_{0}\left[-12 r_{0}^{12} r^{-13}+12 r_{0}^{6} r^{-7}\right]=U_{0} 12 r_{0}^{6} r^{-7}\left[-\left(\frac{r_{0}}{r}\right)^{6}+1\right] \nonumber \]

The equilibrium point occurs when \(r=r_{0}\) The second derivative of the potential energy function is

\[\frac{d^{2} U}{d r^{2}}=U_{0}\left[+(12)(13) r_{0}^{12} r^{-14}-(12)(7) r_{0}^{6} r^{-8}\right] \nonumber \]

Evaluating this at \(r=r_{0}\) yields

\[\left.\frac{d^{2} U}{d r^{2}}\right|_{r=r_{0}}=72 U_{0} r_{0}^{-2} \nonumber \]

The angular frequency of small oscillation is therefore

\[\omega_{0}=\sqrt{\left.\frac{d^{2} U}{d r^{2}}\right|_{r=r_{0}} / m} \nonumber \]

\[=\sqrt{72 U_{0} / m r_{0}^{2}} \nonumber \]